Supplementary Table 3. Common cognitive biases and flaws in SLE

advertisement

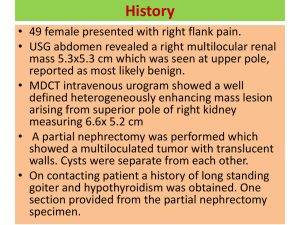

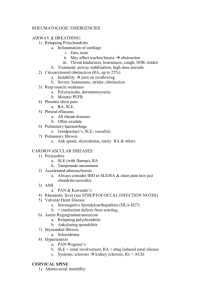

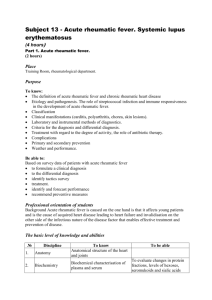

Supplementary Table 3. Common cognitive biases and flaws in SLE diagnosis and management Step in diagnosis Bias Definition Example Development of differential diagnosis Availability recall Referring to what comes to mind most easily. Differential influenced by what is easily recalled, creating a false sense of increased prevalence of the condition Influenced by a recent case of sagittal sinus thrombosis in a patient with SLE headache, clinician thinks of venous thrombosis in subsequent SLE patients with headache, neglecting more common causes such as migraine Representativeness (Judging by similarity) Clinical suspicion influenced solely by signs and symptoms, and neglects to consider competing diagnoses A young woman with low grade fever, malaise, arthralgias and myalgias interpreted as SLE flare rather than as a viral illness Confirmation (pseudodiagnosticity) Assigning preference to findings that confirm a diagnosis or strategy. Additional testing confirms suspected diagnosis but fails to test competing hypotheses Acute onset of pleuritic chest pain in a woman with SLE and antiphospholipid antibodies with a small pleural effusion interpreted as pleurisy without testing for pulmonary embolism Anchoring and adjustment Sticking with a diagnosis. Inadequate adjustment of differential in light of new data results in a final diagnosis unduly influenced by initial impression Nephritis in a patient with positive ANA and rheumatoid factor. Framing (bounded rationality) Assembling elements that support a diagnosis. Clinician stops search for additional diagnoses after anticipated diagnosis made A young woman presents with autoimmune thrombocytopenia and is given the diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura but the malar rash and concurrent arthritis are being missed Premature closure Failing to seek additional information after reaching a diagnostic conclusion A young woman with fever, leucocyturia and haematuria assumed to have urinary tract infection but ignoring significant proteinuria due to SLE nephritis Narrowing of differential diagnosis, selection of diagnosis and validation Fever, arthritis and a heart murmur attributed to SLE and not to endocarditis A middle-aged woman with seizures and negative workup including ANA and anticardiolipin antibodies but clinician missed the malar rash and the photosensitivity Selection of a course of action Outcome Clinical decision is judged based upon the outcome rather than the reasoning and the evidence supporting the decision SLE patient with pulmonary embolism and pericarditis develops hemopericardium and tamponade as a result of anticoagulation. The clinician believes it was a mistake to anti-coagulate based upon this complication Omission Undue emphasis on avoiding adverse effect of a therapy results in underutilization of beneficial treatment Patient with severe proliferative glomerulonephritis is not offered immunosuppressive therapy because of the fear of infections Data modified from Kassirer (2010)1. 1. Kassirer, J.P. Teaching clinical reasoning: case-based and coached. Acad Med 85, 1118-24 (2010).