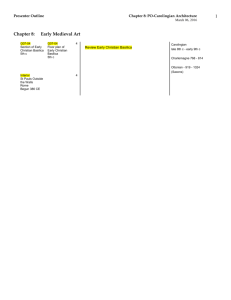

Outline 2/10

advertisement

ARCH 4843 / ARHS 4983 / HIST 3983 / HUMN 3923H / ARCH 4023H Medieval Architecture Outline 2/10/11 The Carolingian Renascence: New Thoughts on the Old Basilica? For additional background reading covering Carolingian and Ottonian architecture: Michael Fazio, Marian Moffett, Lawrence Wodehouse, A World History of Architecture (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008), chapter 8, up through pre-Romanesque. On reserve at the Fine Arts Library. Marvin Trachtenberg, Architecture, From Prehistory to Postmodernity (New York: Abrams, 2002), ch. 5, up through pre-Romanesque. On reserve at the Fine Arts Library. Important recent books on early medieval architecture: Charles McClendon, The Origins of Medieval Architecture: Building in Europe, A.D. 600-900 (Yale University Press, 2005). Jerrilyn Dodds, Architecture and Ideology in Early Medieval Spain (Penn State Press, 1990). Tomás Ó Carragáin, Churches in Early Medieval Ireland: Architecture, Ritual and Memory (Yale University Press, 2010). Key buildings: • San Pedro de la Nave, near Zamora, Spain c. 691, Visigothic • The Gallarus Oratory, 11th cen., Kerry Co., Ireland • Fulda: Abbey church of St. Boniface at Fulda, Germany, 790-819, Carolingian • St.-Riquier (St. Richarius) or Centula Abbey, St.-Riquier, France, 790-99, Carolingian • Corvey Abbey church, near Höxter, Germany (state of Westphalia), 873-85, Carolingian • St. Michael’s at Hildesheim, Germany, 1010-33, Ottonian • The Palace Chapel at Aachen, Germany, ca. 792-805 (not a basilica; coming next week), Carolingian • The Plan of St. Gall, drawing an of ideal monastery, ca. 830 (coming later in week 6), Carolingian Get familiar with the Carolingian basilica and the names of its parts: crossing towers turrets westwork I. From simple central-plan baptisteries, mausolea, and martyria to larger, more complex, more sophisticated geometrically cntral plan congregational buildings (Santo Stefano Rotondo, San Lorenzo in Milan, San Vitale in Ravenna) Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, Rome, ca. 350 (Early Christian) San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, 526-47 (Byzantine) II. The significance of stone masonry in early medieval churches outside of Italy Does stone masonry signify Romanness (Romanitas) on its own? A. Stone masonry combined with basilical form: San Pedro de la Nave, Zamora, Spain ca. 691 (Visigothic) St. Mary’s at Reculver in Kent, England 669 (Anglo-Saxon) St. Peter’s at Monkwearmouth, Durham Co. England, ca. 675-700 (Anglo-Saxon) B. Problematics of wood churches C. Simple, single-cell churches in early medieval Ireland in three construction methods: Does masonry construction (drystone or mortared) signify romanitas? Organic (turf, wattle, or wood) Drystone Mortared corbelling vs. true arch Or allusion to Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem? The Gallarus Oratory, 11th cen., Kerry Co., Ireland St. MacDara, 10th cen., Galway Co., Ireland III. Carolingian Empire and Carolingian Renovatio (renascence): revival of large scale basilica architecture Carolingian period (c. 750-950) A. What Roman building is “revived” in Fulda’s St. Boniface, and how so? St.-Denis, Paris, 768-75 (Carolingian phase) Carolingian basilica of St. Boniface Fulda, Germany, 790-819 B. Intense interest in verticality (Roman?) in Carolingian basilica design (see diagram on first page of outline) Corvey Abbey in Saxony (Germany), 873-85 with original state of westwork restored Sections through Corvey’s weswork C. Are crossing towers suggestive of a bay system or a timber-framing approach to construction? D. Ottonian design: How might alternating piers and columns in basilica nave arcades suggest the importance of the geometry of the crossing square? St. Michael’s at Hildesheim, Germany, 1001-1031 (Ottonian)