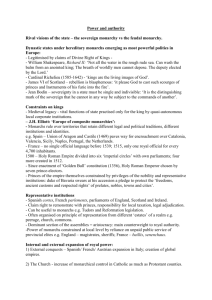

Power and authority Key theme – rival visions in Early Modern

advertisement

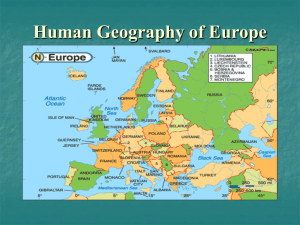

Power and authority Key theme – rival visions in Early Modern Europe of how power should be organised within a state, city and kingdom. Dynastic states under hereditary monarchs emerging as most powerful polities in Europe: - Legitimised by claims of Divine Right of Kings - William Shakespeare, Richard II: ‘Not all the water in the rough rude sea. Can wash the balm from an anointed king; The breath of worldly men cannot depose. The deputy elected by the Lord.’ - Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) - ‘kings are the living images of God’. - Jean Bodin – sovereignty in a state must be single and indivisible: ‘It is the distinguishing mark of the sovereign that he cannot in any way be subject to the commands of another’. Constraints on kings - Medieval legacy - vital functions of state practised only for the king by quasi-autonomous local corporate institutions. – J.H. Elliott: ‘Europe of composite monarchies’: - Monarchs rule over territories that retain different legal and political traditions, different institutions and identities. e.g. Spain – Union of Aragon and Castile (1469) paves way for encroachment over Catalonia, Valencia, Sicily, Naples, Portugal, the Netherlands. - France – no single official language before 1539; 1515, only one royal official for every 4,700 inhabitants. - Since enactment of ‘Golden Bull’ constitution (1356), Holy Roman Emperor chosen by seven prince-electors. - Princes of the empire themselves constrained by privileges of the nobility and representative institutions: duke of Bavaria swears at his accession a pledge to protect the ‘freedoms, ancient customs and respected rights’ of prelates, nobles, towns and cities’. Representative institutions - Spanish cortes, French parlements, parliaments of England, Scotland and Ireland. - Claim right to remonstrate with princes, responsibility for local taxation, legal adjudication. - Often organised on principle of representation from different ‘estates’ of a realm e.g. peerage, church, commons. - Dominant section of the assemblies = aristocracy: main counterweight to royal authority. -Power of monarchs constrained at local level by reliance on unpaid public service of provincial elites e.g. England – magistrates, sheriffs; France – baillis, senenchaux. Italian city states e.g. Genoa, Florence, Venice, San Marino, Lucca. - Republican, humanist ideologies – principle of ‘libertas’. - Wider levels of participatory politics than within monarchies, but still governed by elites. - Oligarchical tendencies in Venice: c. 40 ruling families. - Europe-wide influence of literature written in defence of the city-states e.g. works of Niccolo Machiavelli, Francisco Guicciardini. - Influence models of civic governance in other parts of Europe: - Collinson, ‘Monarchical Republic of Elizabeth I’; Goldie - C17th England an ‘unacknowledged republic’. Internal and external expansion of royal power: 1) External conquests/creation of global empires. - Italian Wars (1494-1559) = expansion of French, Austrian, Spanish monarchs. James Whiston, English economist (1693): ‘For since the Introduction of the New Artillery of Powder Guns, &c and the Discovery of the Wealth of the Indies, War is become rather an Expence of Money than Men. Success attends those that can most and longest spend Money’ 2) The Church - increase of monarchical control in Catholic as much as Protestant counties. - Act in Restraint of Appeals (England, 1533): that ‘this realm of England is an empire... governed by one supreme head and king having the dignity and royal estate of the imperial crown of the same, unto whom a body politic... be bounden and owe to bear next to God a natural and humble obedience’. - 1516 – Concordat of Bologna – French monarch granted right of nomination of bishops. - Principle of cuius region, eius religio as basis for Peace of Augsburg, 1555. 3) Expansion of the court into centre of government. -1561 – Permanent Spanish court fixed at Madrid - Emergence of professional government administrators as key royal advisers from outside ranks of the aristocracy e.g. Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell under Henry VIII. 4) Attempts at greater uniformity over provinces – make monarchies less ‘composite’. -1536-53 – Tudor crown incorporates Wales into English system of government; imposes closer control over Ireland through English Lord Deputies, policy of ‘surrender and regrant’. - Richelieu’s France - creation of intendant officials, 12 out of 16 provincial governors dismissed. - Count of Olivares under Philip IV at Spain – aim at ‘one king, one law, one coinage’, Resistance to royal centralisation creates regional, provincial, aristocratic rebellions: - 1567 – 1602 – revolt in the Netherlands against Spain leads to creation of Dutch Republic. - Rebellions against Elizabeth I in Ireland 1569-73, 1579-83, 1594-1603. - 1638-42 – Rebellions in Scotland and Ireland precipitate English Civil War. - 1640-48 – Rebellions against Philip IV in Naples and Catalonia, breakaway of Portugal, - 1648-53 – Fronde Rebellion creates civil war in France. - Rebels claim to stand for legal and political tradition and methods of government. Crown vs Church? - Internal conflicts when a region possesses different religious identity to a king e.g. Protestant Netherlands vs Catholic Spain; Catholic Ireland vs Protestant England. - Radical doctrines sparked by Reformation and Counter-Reformation justify taking up arms against a heretic prince. - Calvinist thinkers John Knox and Andrew Melville justify deposition of Mary, Queen of Scots (1567) on religious grounds. - Catholic fanatics assassinate William of Orange (1584) Henri III (1589), Henri IV (1610). - James VI of Scotland attacks religious extremists who believe that ‘killing of Kinges is an acte meritorious to the purchase of the crowne of Martyrdome’. Conclusion – gradual encroachment of royal power in Europe, but a contested process: - Kingship by mid-C17th still rests on compromise and negotiation between monarchs, provinces and institutions.