Incorporating the Arts and Humanities in Palliative Medicine Education

Incorporating the Arts and Humanities in Palliative

Medicine Education

Lucille Marchand, MD, BSN

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” Albert Einstein

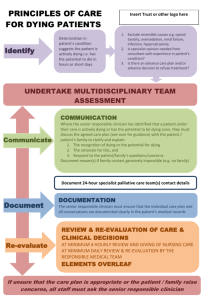

Goals of care for the dying person include optimizing well-being and quality of life, relief of distressing symptoms, empowered decision-making, support of caregivers, and effective life closure for a peaceful and meaningful dying and death.

Palliative medicine, which focuses on expert symptom management and optimal communication regarding decisionmaking, incorporates relationship centered care that values all parts of a person: their mind, body and spirit. It values the entire life cycle especially as a person nears death. Yet, palliative medicine is often given little time in our medical curricula, and the teaching of it is often done in a highly clinical, detached manner. Emotion is left out of giving comfort, facilitating the dying process, and engaging in effective communication about patient and family goals and decisionmaking. How can this be? When one examines the prose and poetry pieces in a prestigious medical journal such as the Journal of the American Medical Association, predominantly, these works often touch upon grief and loss, death, isolation and loneliness. Can our educational methods also touch what is real? Can we touch the raw emotion that comes with mortality or with pain, be it spiritual, emotional or physical pain? Or must it stay clinical and therefore, detached from life? We value what can be counted, but the essence of our most compassionate and effective work with patients is often beyond what is counted. Teaching what is needed requires that we include stories about what people experience as they become ill, and what will make them heal, not just fixed. The use of images, stories, music, and movement in teaching bring learners into the experience of being ill and dying, in order to deepen the well of understanding and relationship centered care. Without this felt experience, we are robots dispensing mechanical interventions for wounds touching the soul. The disconnection is profound, and our patients are left in isolation and pain. Medical practitioners feel frustrated, missing the profound opportunity to truly make a difference, yet not knowing that the emotional sphere is where their best work and service lies. This paper describes over ten years experience I have had with incorporating the arts and humanities into palliative medicine education with resident physicians, medical students and clinicians.

In their first week of residency, many resident physicians experience their first death pronouncement. Many will dread this moment, and this discomfort will live with them throughout residency, if this topic is never brought into the light. Residents tend to denigrate this aspect of caring because they see no therapeutic value in it. The person is dead, and there is nothing to do. Yet, the death pronouncement is an important ritual in medicine that reminds us that all our patients will eventually die, we will die, and how do we continue caring for patients knowing this inevitability? How can we help the family and friends of the deceased at this point? Yet, how to comfort when nothing can be done to prevent death is a very important lesson to be learned. How do we comfort with our

presence? How can we be fully present to the final significance of this moment? What can we learn about life and medicine, knowing that the life cycle must include death, just as it includes birth?

Stories help us learn what is important about our work at this time. The specific methods and protocols we use in death pronouncement are described in previous articles.

(1, 2, 3) There are many written accounts of emotions and experiences surrounding death pronouncements from learners and families.(4,5,6) Excerpts from a number of these pieces are read during the introduction to the workshop and discussed. The most powerful teaching tools, however, are the stories from senior residents, passing on their wisdom to junior residents. The transfer of knowledge, experience and emotion help these junior residents feel the power of this profound ritual. For the first time this past year, we had no senior residents to tell their stories, and the impact of the workshop was significantly less. Stories encourage us to confront our fears with a community of colleagues surrounding us, supporting us, and witnessing the deep commitment we collectively hold to comfort and care for others during difficult times.

In teaching palliative medicine, I incorporate the developmental schema created by qualitative researcher and clinician, Bernice Harper, who studied how health professionals cope with dying patients in their professional development. (7) Her schema of this developmental process incorporates her observations and research data and contains five stages of growth: intellectualization, emotional survival, depression, emotional arrival and deep compassion. Intellectualization, which characterizes how medicine is predominantly taught, and which also reflects the developmental phase of most clinicians, is the stage where mental processes such as analysis predominate. The focus is on the disease, and its diagnosis and treatment, rather than the person. Emotion is seen as irrelevant and distracting. Emotional survival describes the stage when clinicians are touched by the emotions of the patient, often causing discomfort since learners are taught to avoid emotion with patients at all cost. The learner feels overwhelmed by the patient situations faced that stir deep emotion such as the dying process. This is a difficult stage for the clinician and often a time of profound connection with patients, together with sadness and guilt that the patient is dying. Depression occurs when the learner feels overwhelmed by difficult emotions regarding a patient or situation.

At this point, the learner either works through this stage, or returns to intellectualization with a sense that emotions and emotional connection to patients is dangerous and must be avoided at all costs. The clinical attitude here is one of separation from the patient for the clinician and patient’s protection. Yet, processing of these difficult emotions with the support of mentors can lead to professional and personal growth. If the learner works through the stage of depression, emotional arrival can occur. This is a stage when emotions are accepted as an intimate, essential component of caring for patients.

Emotions are viewed as normal rather than avoided as dangerous. A clinician learns to cope with the loss of the relationship with the dying patient and there is increased comfort with death. The final stage is deep compassion, where connection with patients is deeper, and death is seen as a normal part of the life cycle rather than failure, with an accompanying sense of freedom and satisfaction in sharing the dying process with the patient.

Using this schema with clinicians, the timeline for their professional development is explored with time for reflection on the experiences they have had with patients, and

what support they need to continue on this trajectory. A discussion ensues about the merits of progressing in this process. A brief narrative is written about any stage in the schema that is meaningful to the student or clinician, and either in small groups, dyads, or large group, the narratives and reflections are shared if the learner is willing to share their work. I often use poems that I have written about my own growth through the developmental stages. (8,9,10,11) These are shared if learners do not feel comfortable sharing their own work, or if my own narratives are needed to stimulate discussion.

Pain is an issue that is very complex, and it is so easy to misunderstand or blame the patient. If learners have not experienced significant pain themselves, it is difficult to empathize with patients. How pain affects a person’s emotional state is also important for learners to appreciate, since the under treatment of pain remains a disturbing issue in palliative medicine. I often begin my workshops and seminars on pain assessment and management with a compelling poem called the “Prey of Pain” by Bonnie Raingruber.

(12) The poem highlights how spiritual, physical, and psychological pain is difficult to differentiate, and how attention to all these dimensions is essential in the effective management of pain. This poem was also recently incorporated into a monograph on pain management for family medicine residency education. (13)

Teaching on grief and loss is brought to life with stories about grief, loss, and recovery. There are countless books, poems and stories about grief and loss in the popular literature, and in journals such as the Journal of the American Medical

Association. Almost all medical journals incorporate a column on reflections, poems and stories. The Healer’s Art is a medical student elective course created by Rachel Remen,

MD, and is now taught in 53 medical schools. Her course examines wholeness and healing, grief and loss, awe and mystery, and care of the soul, and incorporates the arts in the teaching methods. Students draw a picture of a quality they want to strengthen in medical school, share stories, read poems, journal, and write a poem in the form of their own Hippocratic Oath. Their creativity is encouraged in remembering and fostering their strengths. (14)

Palliative medicine needs the arts to bring the emotion, connection and relationship back into medicine. Mind/body/spirit medicine cannot be an abstraction, and separate from our real experiences caring for patients. As teachers and clinicians, our creativity awaits to be of service to our hands, hearts and minds. Intellectualization is a lonely place for the patient and clinician. The art is needed to balance the science. The heart is needed to balance the mind.

References:

Marchand L, Kushner, Siewert L. Death pronouncements survival tips for residents.

American Family Physician .1998;58(1):284-85.

Marchand L, Kushner K. Death pronouncements: using the teachable moment in end-oflife residency training. Journal of Palliative Medicine , 2004; 7 (1):80-84.

Marchand, L, Kushner, K. Death Pronouncements: Surviving and Thriving through

Stories. Family Medicine 2004; 36 (10): 702-704.

Temte, J. Late night call to 6 West. WI Med J 1991; 90: 509.

Johnson-Magill, V. Mother’s day trauma. Fam Pract News 1998; June 1: 10.

Lermen, R. Death Rituals. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 384.

Harper, Bernice. Death: The Coping Mechanism of the Health Professional .

Greenville, S.C.: Southeastern University Press; 1977.

Marchand, L. Be not afraid. Unpublished poem.

Marchand L. “Outrage” (poem).

Families, Systems and Health . 2000;18(3):377.

Marchand L. “Listen” (poem).

Families, Systems and Health . 2001;19(4):451.

Marchand L. “Letting Go” (poem).

Journal of Palliative Medicine . 2002;5(3):425.

Raingruber B. Prey of pain. JAMA 2002;287:2329.

Douglass AB, Bauer L, Jonas P, Marchand L, Marvel K, Maxwell T,

Rosenthal M, Whitecar P. Pain Education in Family Medicine.

(Monograph) Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, 2005.