TWENTY FIRST LECTURE OF THE - Organization of American States

advertisement

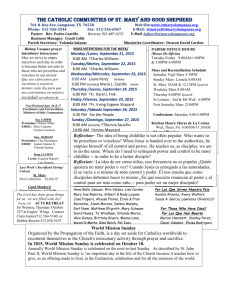

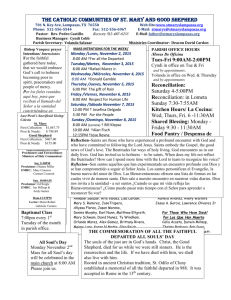

THIRTY-FIRST LECTURE OF THE OAS LECTURE SERIES OF THE AMERICAS ROBERT B. ZOELLICK President of the World Bank Group “A Conversation on the Inter-American Agenda” Monday, December 8, 2008 Hall of the Americas Organization of American States Washington, D.C. THE SECRETARY GENERAL (José Miguel Insulza): ¡Muy buenas tardes! Good afternoon and welcome, bienvenidos a esta thirty-first edition of the Cátedra de las Américas, and to this Hall of the Americas of the Organization of American States (OAS). Only a few hours ago we were here, at this building, celebrating a very significant event in the history of country resolution in the Americas with the signature of the Agreement between Belize and Guatemala to try to resolve their territorial differences. We are very proud of this; that’s why I’m referring to it. This is one of the roles of our Organization, which is to promote peace and security in the region, and peaceful conflict resolution. In the same sense, we are also a large forum for the Americas to discuss the main issues that the region faces, such as democracy, human rights, development, and social cohesion. These are precisely the issues, which have to do with the Cátedra de las Américas. We have the great honor today, on the thirsty-first edition, to have with us the President of the World Bank, Mr. Robert Zoellick, and I wish to say that this is one event—the first of a series—that we are organizing that has to do with the preparation of our Summit, the V Summit of the Americas, which will be held in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, from April 17 to 19, 2009. The issue of the Summit is the future of our citizens through the promotion of human prosperity, energy security, and sustainability. Of course, it has a lot to do with the economic situation of the region today, and President Zoellick is, indeed, one of the most relevant persons to speak to us about this. We have chosen a new format for the meeting today. President Zoellick will have a conversation on this and any other topic that they deem interesting with a person who is very well known in this Organization, Mr. Bernard Aronson. Mr. Aronson, as those who are better acquainted with the interAmerican system know, was Assistant Secretary of State for the Hemisphere some years ago. He has been very active in matters related to the Americas, and he will be sustaining a dialogue with President Zoellick. I will leave you now with the Chairman of the Permanent Council, Ambassador Reynaldo Cuadros, Permanent Representative of Bolivia, who will briefly do the introduction. Thank you very much. [Applauses.] THE CHAIRMAN OF THE PERMANENT COUNCIL (Ambassador Cuadros): ¡Muy buenas tardes a todos! Quiero, en primer lugar, dar la bienvenida al señor Robert Zoellick y al señor Bernard Aronson que lo acompaña. El Secretario General ha explicado en realidad el propósito de este encuentro, así como la importancia y la relevancia de hablar de estos temas ahora. Todos ustedes tienen la biografía del señor Zoellick. No obstante, quisiera destacar, puesto que las personas se conocen fundamentalmente por sus ideas, que el señor Zoellick ha sido uno de los principales promotores del mercado libre a niveles globales, regionales, bilaterales. También ha respaldado mercados abiertos. De 2001 a enero de 2005, el señor Zoellick ha servido como el décimo tercer Representante de Comercio de los Estados Unidos. Ha sido, de 2005 a 2006, Subsecretario de Estado en el Departamento de Estado de los Estados Unidos y actuó como Oficial Principal de Operaciones. Desde el 1ro de julio de 2007, es el décimo primer Presidente del Banco Mundial. El Banco Mundial está compuesto de 185 Estados Miembros. Anteriormente, de 1993 a 1997, el señor Zoellick se desempeñó como Vicepresidente Ejecutivo de Fannie Mae, una corporación financiera en el tema inmobiliario. Tenemos hoy una oportunidad muy especial para conocer, de una de las personas más famosas en el mundo, cuáles son las ideas que nos va a presentar en relación a una nueva imagen o un nuevo papel que tendría el Banco Mundial, después de que varias de las ideas que el Banco Mundial promovió han sido cuestionadas a raíz de la caída financiera, incluyendo la gran crisis financiera que se ha dado en los Estados Unidos y que ha afectado al mundo entero. El tema del mercado es un tema muy controversial. Tenemos, entonces, un gran desafío. Aquí vamos a escuchar en palabras del señor Zoellick cómo es la nueva visión regulada de los mercados y seguramente también cómo vamos a poder progresar en esto. El tema de la privatización ha sido un punto también que ha sido estimulado largamente por el Banco Mundial, incluso en áreas como el agua, la educación y la salud. Vamos a ver cuál es la nueva visión. Finalmente, en la última sesión del Banco Mundial y del Fondo Monetario Internacional, algunas de las cuestiones que han surgido sobre la reforma necesaria del Banco Mundial es la participación en el mismo de los países en desarrollo en igual número que los países desarrollados. La India, por ejemplo, hizo notar su preocupación por la cual solamente 1.4 % de los países en desarrollo participan en el Directorio del Banco. Por lo tanto, vamos a poder escuchar directamente del Presidente del Banco Mundial expresarse directamente sobre estos y otros desafíos, junto con las nuevas ideas que puedan haber para resolver el tema financiero y la crisis que están aquejando al mundo. Tengo ahora el placer de dejar al señor Zoellick con ustedes, y después la audiencia podrá hacerle preguntas. Muchas gracias. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): It is a great pleasure to be in this historic chamber, which has witnessed so much history that was vital to our hemisphere, and it is a particular pleasure to be with my old friend and former colleague, Bob Zoellick. You have already seen his distinguished résumé. I would just add one point. From the time we had together, on every matter that was vital to Latin America during the time I was Assistant Secretary of State, whether it was resolving the conflicts in Central America, negotiating the North American Free-Trade Agreement (NAFTA), promoting debt reduction or promoting democracy, Bob was always an extremely strong supporter and ally of this hemisphere. He remains so today in his new position as President of the World Bank. So, Bob, let me start by looking backwards and looking ahead. When you and I were in government together from 1989 to 1992, Latin America had just suffered a lost decade; hyperinflation was raging in many economies; most of the major economies were suffering from a debt crisis. From that vantage point, the region has made enormous progress. Today, most of the economies are boasting fiscal and trade accounts surpluses. Hyperinflation does not exist though there are a few places where it’s present, but it has largely been controlled. Economies have been growing in most part, so a lot of progress has been made. On the other hand, the development gap that still exists, not just between Latin America and the Caribbean and the United States, but even with the Asian countries, persists. The region doesn’t have the same growth rates or savings rates, so I’d ask you two questions: Do you see the glasses half full or half empty with regards to this hemisphere? And how do you see this hemisphere closing that development gap and what’s the role of the World Bank in that process? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): Thank you, Bernie. Let me just thank the Secretary General for his kind invitation to be here with all of you. I’ve been in this Hall many times before on different occasions, so it’s a real honor to be invited back as part of these series. Thank you, Ambassador, for your introduction. I can’t help at this point, Bernie, but be very focused on the months to come. My major message, which I think everyone now recognizes, is that we’re in a very difficult period that started out as a financial crisis and then became an economic crisis. unemployment crisis. I’m afraid in 2009 it will be an There are elements still dating back to the food and fuel problems that make it very much a human crisis. And so, you are correct that the region has made very important strides over the past decade, but I’m afraid this is going to be a particularly stressful period that we are headed into. Looking beyond that, I would say that as everyone here knows, you really have to disaggregate into regions. So, you have some countries in Latin America that have very much strengthened their fiscal and debt positions, have had relatively open economies, flexibility in exchange rates. Those are the countries that are best positioned to deal with the turmoil to come, although many of them have been major commodities exporters, and so, they are going to have to deal with what looks like to be a big turnaround of commodities prices. You have other countries that have not gone as far in taking on the challenges. They have more rigidities, and those countries, I think, are going to face more difficult days ahead. Central America, which has been very much linked to growth in North America based on remittances and on trade patterns, has less room to maneuver the monetary or fiscal policy. I’m particularly concerned about the Caribbean countries, because with the drop-off in remittances and tourism, I think, they are going to be under special strains. But implicit in your question is the idea—one that I have always liked—which is: Can you take a moment of challenge like this and make it into an opportunity? And you were, I think, properly making an observation that I often make to my friends in Latin America and the Caribbean when I work in this region—since my career takes me to all regions of the world; in fact, later this week I’m heading to China—which is that they need to look beyond this, the Western Hemisphere, because much of the competitive challenge is global. While many countries in the region have strengthened their fiscal and monetary positions and their effort against inflation, there are two major challenges that still have to be undertaken and would help in a point like this. One is some of the structural challenges to allow a more flexible, adaptative, competitive economy; and the other is the investment in social development, education, some of the basic health care. I think the challenge for the upcoming generation of leaders in the region will be how to go beyond this crisis and look to continue to invest in those foundations for future growth. There’s no doubt that there have been some very significant developments. You can see it in poverty reduction in Brazil, Chile, Mexico Peru, and others. We’ve learned some things from this. For example, the program that Mexico launched on the conditional cash transfers called the Oportunidades program. In Brazil, it’s the Bolsa Família. There are versions of these in Chile and Peru, and elsewhere. In this crisis, we are now looking with some Central American countries to see how one can apply it. Those programs are vital whether in good or bad times. In good times, they help give a broader segment of the society a feeling that they can climb the ladder of opportunity because, as many people know, those programs direct cash transfers to those most in need, but they link it to sending kids to school and basic health check-ups, which are very important for women in particular. But, in a moment like this, they also become the vehicles to try to put in support for those under stress. I guess the last thing I will say that is particularly distinct about this region is that, as you and I worked on some of the issues of democracy, which are at the heart of the OAS and others, I think the structure reforms relate not only to the economics but opening up to society. What we saw was a more open political process, but many groups that have been cut out, not just for years or decades, but for centuries, particularly indigenous people, didn’t feel they had that ladder of opportunity. This created some dangers that I think could be exacerbated under periods of economic stress. I was just in Haiti not long ago. Here is a country that was one of the first to show the threat of high food prices on social disruption. Then, it was hit by four hurricanes. Since it is the least-developed country in the Hemisphere, in some ways that’s a warning sign of what could happen to others if this difficulty persists. My main thought today would be that 2009 is going to be a difficult year. No one knows how deep this is going to run, and no one knows exactly how the recovery is going to come about, and so, one has to be prepared for dangers. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): So, if I am a Finance Minister who accepts your diagnosis and your prescription for the agenda of social development and market and trade opening, how does the World Bank fit into that? How do other multilateral development organizations fit into that agenda? What were you involved in and what are you focusing on these days? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): One of the most important elements is that, fortunately, we had already changed some of our lending policies for the middle-income countries, which is what most of the countries in the region are, to lower some of the prices, make it simpler, make the maturities more flexible, do local currency financing. What we are finding now is that even some of the economies that have done an excellent job of maintaining their fiscal position and having very well-run budgets over the past five or ten years are finding it hard to get access to international finance, in part because many of the developed countries have put so many government guarantees out there that it’s going to be hard to be able to access money for budgets if you have to go to international markets. If you combine that danger with the fact that one of the lessons of the 97-98 financial crisis is to try to help countries avoid contractionary policies, you find countries—Mexico would be one example; Indonesia is another—where they may want to run very modest budget deficits as a percentage of the GDP. Mexico is still looking at, I think, about 1.8% of the GDP. It is similar for a country like Indonesia. However, they are not certain that they can get the borrowing to run that deficit. They are not really in a position where they need to go to the IMF’s help. We have various lending products. Some of them are contingency lending products that we will use to increase our lending with Mexico, Indonesia and other countries in the region. In Brazil, we’re expanding some of the lending with the states, which are part of Brazil’s broadening of its reform process, but what is important for people to recognize is that many people associate the World Bank with money, because it’s called “bank”. In reality, what the Bank does best is try to help bring and bridge knowledge and learning from around the world. It may be conditional cash transfer programs; it may be microfinance programs; it may be governance and anticorruption programs; it may be fiscal management programs as we’re using in some Brazilian states. And then, combine that with projects that have reached beyond individual projects. So, how can we build markets, institutions, and capacity? That may be covert markets; it may be microfinance markets. We are working with a number of countries in the region to build their own local currency bond markets, so they have those accesses. And then, we do bring capital to the game as well. Let me bring this again home since it looks like you’ve got a folder that looks like it is from Colombia. One of the things that we did recently with Colombia was take advantage of the fact that we have longer terms for some of our lending and local currency to help finance a student loan program for poor students. And so, by having the maturity of our loans match the maturity of student loans, you didn’t have to worry about an asset liability mismatch. By funding it in local currency, we avoided the foreign exchange risk. So, this is an aspect of a social development program that is also investing in the future, and so, we have a number of those tools available. In the Caribbean and in Mexico, we have developed, under various models, insurance products for a natural catastrophe. So, whether it’s a hurricane and wind and rain in the Caribbean and Mexico, whether it’s an earthquake, as your experience shows and as a lot of people in this region would know, they can do a very good job as some countries in Central America did, but they would be extremely vulnerable to an earthquake that could set them back in the course of years. We also put in some special projects trying to deal with the stress of safety net programs for food, and we have used that in a number of countries in the region, starting with Haiti. In general, what we’re trying to do at the Bank is understand our clients’ needs and then approach these as a problem-solving exercise as opposed to just an analytic one, and try to match the range of projects, whether they be knowledge transfer, financing, or different models. This includes not only the formal work that we do through the public sector side, but also the International Finance Corporation (IFC). If you look at our private sector work in IFC, you will see that we are trying to expand, for example, trade finance facilities now, because you’ve seen a big drying up of that credit. One of the things that people have to be alert to is the nature of the problem in the current environment. It is one that you can’t always predict, so you saw a trade drop-off because of demand, but all of a sudden you also saw people have a hard time paying their credit due to the credit contraction. So, we are trying to move quickly with various partners to deal with that sort of issue. Another area would be infrastructure projects. One of the lessons again of the 97-98 financial crisis was infrastructure projects can be good to not only keep people at work, but they also set the foundation for future growth. We discovered a lot of viable infrastructure projects. We are running out of funding mid-stream, so we’re trying to set up a facility, through the IFC and also on our public sector side, to try to support some of those projects. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): You know, it’s interesting because I was waiting to hear whether the word infrastructure would be mentioned; you got there at the end. Most people’s sort of memory in the Bank was traditionally big infrastructure projects. That was the mandate years ago, but it sounds like the focus has shifted enormously. I just wonder what the relative balance in the region is between your involvement in the financing of traditional infrastructure projects, whether by helping existing ones that need financing or new ones, and this whole new area of social development, development of financial markets, insurance products, and the like. Is the Bank fundamentally gravitating, in terms of its focus, to that new mandate, and what is the relative balance? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): We have to add another one, which is climate change. There is another whole aspect that is related to that, and I think part of the challenge is: Can you find win-win opportunities, particularly in a period of stress like now? Let me just build on the climate change, because it is also related to a broader concept of infrastructure. We put together some $6 billion of new climate investment funds in order to help with technology in forestation adaptation. Mexico may be one of the countries first in line, and it’s not, in a sense, a technology that has to be sort of developed. This is existing technology to deal with transportation systems. You can save energy; you can have reduction of carbon; and you can also have much more efficient transportation systems. And so, we are working with Mexico now on one of the first of those projects. What I would suggest would be different from the old view of the Bank on infrastructure. In the McNamara early era, the Bank kind of did the project. In a sense, what we now try to do is work with the public and private sectors. What we are seeing now is where a year ago the challenge was: How could we work with governments to develop private sector projects for infrastructure? And where the challenge was: How do you define the engineering terms and the financing terms to draw in private capital? It’s different than the old days where you would go to a public works ministry. They would have the engineering plans; they just put in the budget year by year. You had to have the package as a whole, so we would spend time talking with governments about how to create this in different sectors. Given the problems now with private capital, the challenge is: How can you work with BMBS in Brazil? How can you work with the Mexican development banks? How can we help connect some of the public financing, but with an eye towards also being able to draw a private sector financing at a later point since the infrastructure needs in Latin America, to become competitive with the East Asian countries, are enormous? Many of you in the region know about the ports, the roads, the airports, the range of facilities, and you can put the name of your own country in front of it—the X cost of logistics and moving products around. There is a huge need, whether it be electricity, whether it be road transport, or others. There just isn’t going to be enough public sector money to do all that, so if you can make it into an effective return, you want to have a public-private mix. In a sense, part of the message for today, but for the Bank in general, is that we have to be alert to market conditions and changing needs of clients to adjust that mix in order to meet the circumstances. Whether it be an effort from our private sector side, or public sector side, or some combination depends on the times and the circumstances. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): Bob, you started off your remarks focusing rightly on the financial crisis, and it’s no secret to you because you pay a lot of attention to Latin America, that populism is rising back up in a number of countries. The populists would argue that this financial crisis is proof that the Washington consensus, the free-market model, and neoliberalism are a failed project and that we need a new model, which they offer, which is much more statist and authoritarian, and “State control” and “State intervention,” because the free-market model has failed. What would be your answer to those voices in Latin America who make that argument? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): I guess I would give a couple of answers. One is, look at the countries in Latin America that are able to deal best with the trials of the current economies, and the countries that have used the market effectively, whether it be the Chiles, the Brazils, the Perus, the Colombias. This isn’t to say that they are not without their challenges, but I think what you will find is that those that didn’t take those steps that we talked about in the fiscal side, didn’t deal with the inflationary issues and didn’t manage their commodity wealth effectively are going to be the ones that are going to find themselves in difficulty. And you would certainly see that if you look around the world. Secondly, I’ll share with you an anecdote. I was meeting at the time of our annual meetings in October with one of the up-and-coming Asian countries that was asking these questions about markets and private property, and how to use them and the challenges of these. I turned to our Chief Economist Justin Yifu Lin, from China, and I said: “Justin, why don’t you address this question”? He answered that we would have to be very careful getting too far away from using markets. They are very important, and you do really want to develop the property rights, so people would invest. That’s at least the message from the Chinese economist who has used this pretty well. I think the third part is that it is natural, at any time of crisis like this, that people examine the system, and that’s a healthy thing to do. We are both old enough to have lived through a few of these crises, and I’ve seen that people predict the end of capitalism, and then, the next day it starts with a solely different form of capitalism again. I think there’s a message there, which is, there is pragmatism about this. There is a role for the State and probably everyone in this room knows that as you deepen that role, you sometimes can run various risks. You run risks of corruption, political influence, sometimes lack of competition. Let me just connect this with one last thought. At these G-20 meetings and others, in addition to talking about what the World Bank can do like expanding its lending and some of the things that we are doing in the IFC private sector side, some of the things that we are doing for the poorest countries, I sometimes try to remind countries to look two or three steps ahead. So, for countries in this region, I’ve made the point to developed countries to please be careful about all the guaranteed debt that you have out there, because while I understand why you need to do it, at this point, if you don’t discipline or have exit strategies, it’s going to make it very hard for developing countries to borrow. But there is a point that’s applicable to developing countries and developed countries, which is, as you tighten up financial systems, please be very careful that the people who don’t get squeezed out are those who have least access today. So, probably many people in the room and others have worked on issues of microfinance, microcredit and saving systems, and we are doing some fascinating experiments about this in a way to pursue the goal that former President Zedillo of Mexico once said to me. He said: “Look, the problem isn’t often that we have too much in the way of markets; it is that we don’t have enough markets reaching out to enough poor people to be able to access.” As everybody know—and this region in particular has seen this— the big guys can figure out a way to take care of themselves. They get special access and special treatment, but if you tighten up the financial and credit system too much, it is the little guy who loses out. The little guy is often the indigenous person, the small business, the female-headed business, and what I am concerned about is that those are often the big job creators. So, if you are really thinking about job creation, you don’t want to shut those out of the system. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): As most people in this room know, before Mr. Zoellick was President of the World Bank, he was Special Trade Representative to the U.S. President, and during his tenure, he paid particular attention to making progress in the Latin American and Central American free-trade agreement, and Peru, Colombia, and Chile. I suspect everyone in this room and everyone in Latin America is wondering where the United States is going on trade. In a way, the question is: Can we take a yes for an answer? And you are not just a smart policy analyst, but you also understand domestic politics. How hopeful or how discouraged are you that this new Congress, and this new Administration is going to find a new formula to move the trade agenda forward in this hemisphere, or are U.S. domestic politics going to steer us in a different direction? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): I wouldn’t want to fool people. I think that domestic politics are going to make it very difficult. You could see this in the discussions during the campaign, not just at the presidential level, but at the congressional levels, and people hear the debate out there. This is a bigger issue than the United States and Latin America. I do feel that with the type of economic forecast that I was suggesting, you are going to see price discounting, and this is going to lead to a whole series of supposed unfair trade actions. We could be in for a round of protectionism here, not of the formal type, but the informal type. Now, to try to find a positive way to deal with this, I would suggest one thing from the United States side and one thing from the regional side. On the U.S. side, I do think that you have to help people adapt to change. I think that if the U.S. does certain things in health care and the ability when you lose a job to still have access to health-care benefits, as people have tried to do with mobility and pensions—and we have talked about ways that you could have wage-insurance programs—that helps deal with some of the anxieties, but it doesn’t deal with all the fears out there. And so, we’ll take some strength of leadership. And here, I have just noted that you have left several parties out like the Labour Party in Britain and the Labour Party in Australia that have been very pro trade. So, there’s a challenge there for those in that group to try to see that they can help deal with worker anxiety, but not try to follow the false siren call of closing up markets. For the region, I just cannot emphasize enough that I think that the new Administration and others want to get off on the right foot with the region. They value the relationships, so they need to hear from the region whether these things are important to them. Obviously, the Colombian FTA, in some way, should be a no-brainer in terms of the benefits to both economies and to the region as a whole. Based on that, the United States would then have free-trade agreements with Canada, Mexico, Central America, the Dominican Republic, Chile, Peru, and Colombia. The Panama Agreement is also one that should pass. That would cover twothirds of the GDP of the Hemisphere, not accounting the U.S., and twothirds of the people. Now, there are also great opportunities to reduce barriers with Brazil and the other countries that are part of it, including on things like ethanol. So, there is an opportunity there, but I honestly think that it would be important for people from the region to explain its significance. And then, I wouldn’t stop with trade. The whole logic of the trade agreements was that they are not operable by themselves. One of the things that I saw that the Bush Administration launched in its waning days was an idea to try to pull the countries together that have free trade agreements with the United Sates and see how they could link these to their development agenda, their business agenda, and their trade facilitation agenda. And obviously, I think they also included the Caribbean countries, which were part of a preferential trade arrangement. One shouldn’t stop with that. One should look for ways that deepen the integration, and then look at ways with which, one way or another, one could still reach for the goal of free trade in the Americas. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): Is there also an opportunity in energy in the inter-American system that the United States wants to reduce its dependence on foreign oil from unstable parts of the world? There are huge reserves of gas and oil in Latin America. You would think that that’s a natural marriage, and of course, the United States imports 30% of its energy from this hemisphere, but is there a chance to vastly expand that in a win-win proposition? Is that something the Bank is thinking about or playing a role in? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): Well, I think the greater issue there is the price of the barrel. Just to again anticipate dangers here, one of the things we have seen is that when oil prices were about $40 to $50 a barrel, food prices moved to almost a oneto-one relationship where it used to be maybe 20 cents to a dollar. I think that one of the problems is going to be with the great volatility. You won’t have people investing in some of the energy production. You don’t have them investing in some of the equipment for energy production. That’s one of the things that happened when some of the growth of the world economy from China and elsewhere led to the surge of oil prices to $150 a barrel. You could be back to that sort of environment in a matter of years. So, what this would suggest is, frankly, if you could work out some greater understanding, hemispheric or more broadly, about some price range, some assurance at the same time that you focus on some of the things that you could do in energy efficiency and clean technologies, and some of the things to reduce the carbon production, it could be certainly of benefit for the region, and it would interconnect it. Of course, as you and the audience know quite well, in some countries there are very sensitive attitudes about tapping the natural energy or mineral resources in a sense of ownership of the public. And here again, maybe you can actually look at some models from elsewhere. You asked about some of the things that we are doing. I’ve been to the Saudi ARAMCO facility, which is a fantastic company, and I have tried to suggest some contact with PEMEX and Saudi ARAMCO. What you actually see is the way that Saudis run Saudi ARAMCO, which is very different from the way Mexicans run PEMEX. So, you could have a stateowned oil company, but one that operates more effectively for the State. In a sense, part of a broader point that we are trying to do at the Bank is encourage South-South learning experiences, because there is a lot of knowledge and experience of different programs, whether it be social development or energy development that you can share across the developing world. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): I’m going to ask one more question, and I know a lot of people in the audience have questions that they would like to ask President Zoellick. I guess my last question is: When you take this financial crisis, how is this movie going to end? A lot of people watching see central bankers and others scrambling to try to catch up, and shoes are dropping. How optimistic are you to a variety of means, to the stimulus packages, a lot of liquidity being put into the financial markets, interventions in banks? Is this thing stabilizing, or are there more shoes to drop? If Latin America and the Hemisphere can get through 2009, are you hopeful or optimistic that 2010 is going to start to see some improvement, or is this movie “hang on to your steering wheel and hope for the best”? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): It will depend on the actions that people will take over the course of early 2009. I think a number of central bankers have taken the right policies in trying to create liquidity. There’s still a huge lack of confidence in counterparties, and so, I think some of the things that the Federal Reserve has done in recent weeks are worth examining by other central banks. They’re basically creating markets in some of the asset-backed securities. I think you’re going to need a big fiscal response by countries that can do so. I think you’ll see that from the United States. You’ve seen it from Britain; France has wanted to do some; Germany has been more reluctant. I’m going to be in China later and I think China will take additional steps. There are some countries in Latin America that have a little bit more fiscal room, but this is where it’s a challenge. Some of them do not have the same space. Then, the question will be: As the unemployment problem increases—and it will increase—will countries take counterproductive policies of a protectionist nature? I do believe that with the right government policy responses, you could start to see a recovery later in 2009, but it’s extremely difficult to predict, because you have these uncertainties and these events that depend partly on the right policy response. THE INTERVIEWER (Mr. Bernard Aronson): Bob, thanks. That was a fascinating conversation. At least, I learned a lot. I’ll now turn it over to Irene for questions and answers. THE MEDIATOR (Dr. Irene Klinger): Thank you very much, President Zoellick, and thank you very much, Mr. Aronson. I think, Mr. Aranson, you were the longest-serving Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. I see that you have developed some other skill. Maybe those who are buying for that position now might think that they will develop additional skills in the future as well and become wonderful interviewers. Thank you very much for the wonderful job. I would like to open the floor for questions from the audience—our ambassadors, as well as the audience in general. I know our ambassadors well, but I’ll ask others to please introduce yourselves. There is also a microphone that will be going around the room. I have first Ambassador Manuel María Cáceres from Paraguay. Ambassador Cáceres, you have the floor. THE AMBASSADOR OF PARAGUAY (Ambassador Cáceres): Thank you, Irene. This is a great conversation. We all have been interested in listening to comments. I have two questions for President Zoellick. The first one is in his capacity as Head of the World Bank. We have seen with our current financial crisis that developed countries have created huge stimulus packages, in the hundreds of billions of dollars, trillions of dollars, and some important developing countries are also aiding their economies. What about for the small developing countries, Mr. President? Is the World Bank thinking of certain packages in order to aid them to weather this difficult situation? That would be very interesting for us to know. My second question is in your capacity as U.S. trade negotiator. Do you see this current situation as an opportunity for the DOHA Round to come to a successful ending? We could see, as you said, more protectionism between countries, or difficult issues of subsidies, but do you think that somehow there could be room to be optimistic about the successful conclusion of the Round? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): On your first question, let me first briefly summarize the ways the World Bank has been trying to help. For the middle-income countries, which include most of the countries in Latin America, our primary tool is the IBRD lending. We have about $99 billion of outstanding loans, and I announced three or four weeks ago that our capital would permit us to do about another $100 billion of lending over the next three years. Just to give you a point of reference, last year our IBRD lending was about $13.5 billion, in part because some of these product changes. We probably would have been in the mid to high teens. This year, it will probably be $35 billion or in that range. That includes all the countries expanding. On your second question, for the poorest countries we have the International Development Association (IDA) funds, which are grants in long-term loans with no interest. In this region, that would primarily be Haiti and some countries in Central America as well. There, what we are trying to do is every three years, we have to raise those IDA funds from donor countries and sometimes contributions from our own income. We have about $42 billion of those IDA funds. This is in IDA-15, and we’ll try to frontload those as much as possible. Then, the third area is the IFC, our private sector side. As I alluded to with Bernie, looking at the problem of trade finance, we already had relationships with about 60 countries and 160 banks trying to help them to do trade finance. We have increased our credit line for that activity to about $3 billion. We were worried about smaller countries that need to recapitalize their banks. If you are the U.S., or Britain, or France, or Germany, you can just put the capital in, but if you are not, what do you do when your banking system runs out of capital? So, we put together a special fund of $1 billion, and the Japanese promptly joined us and added to it. We are still looking for more to help use our investment knowledge from IFC in banking systems in smaller countries where the macro environment is stable to supply that. We are also trying to create an infrastructure fund for viable infrastructure projects through the IFC. The Japanese, the Germans, and others are looking to participate in that. In addition, we want to keep up the activity that we had for emergency food and safety net projects. We have done a lot of those with countries around the world and in the region. I created a rapid financing facility of $1.2 billion to provide that. We already have about $900 million of it committed. The Australians, the Russians, and some others were going to contribute a little bit more. And then, another area that we are trying to work with the Saudis and some Europeans is an Energy for the Poor Initiative. Here, we are trying to partner with some of their lending institutions to try to deal with those that are the most vulnerable, but also in some of the energy infrastructure— some of it off-grid, and others. Then, I made allusions to the fact of climate change. We do have other climate change funds, and these provide another source to, in a sense, do well by doing good. So, that’s another source of opportunity. What these all come back to, Ambassador, is that what we try to do through our country teams—and we have offices in well over a hundred countries—is to try to understand the special needs and circumstances, and then, customize the support based on these various tools. So, I used some big countries as examples, but whether a country is big or small, we would be able to try to adjust. Some of it is policy advice; some of it is sharing the experience. For example, we’ve talked about safety net programs. In some countries that don’t have the public governance infrastructure, you really need to work with things like Food for Work Programs, or School Feeding Programs. Otherwise, if you can work up to a conditional cash transfer program like some of the others in the region, that’s a slightly better system to have, but we try to work with countries based on needs and circumstances. And, indeed, we do this in concert with others. We do this with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), which is a very good partner, and others in the process. As for the DOHA Round, I hope your hypothesis is correct. I have long said that I believe that last year and before, there was a deal on the table. The nature of these trade negotiations require you to get over a 150 economies in agreement, so it’s like doing a big business transaction with a 150 partners, all reaching unanimity, which is not easy. In that environment, it really requires some of the major players to take the leadership role. In this sense, I think the public actually has a mistaken view of trade negotiations. They have this view that it is like a poker game where one wins and one loses, and you keep all your cards close to your chest. In reality—and many of you have seen this in your own experience—it is a mutual problem-solving exercise. You are trying to liberalize while dealing with the other guy’s politics. The problem is getting the politics aligned globally all at once. In this current environment, for example, there are sensitivities in India. You have Indian elections now; India has been suffering terrorism. That will be a challenge going forward. I will say— and this is in reference to Bernie’s question—I think there would be a good opportunity here for the current Administration to try to see if it can reach a framework and, in a sense, carry some momentum into the next Administration. I’ll be very direct on this part. If you wait for the 535 members of the U.S. Congress to give you a go ahead, you are going to wait for a long time. Their job is basically to criticize and to represent particular interests. It is the job of the trade representative to look across that, try to see the bigger interest and make a deal go forward. At this point, I’m not up on the details and particulars, but frankly, in some ways I would love to be in the position now where in your own country’s interest, you could discipline some of the agricultural subsidies, open markets. One of the odd things about being a trade negotiator is that if you give away too much, guess what you have done? You have probably helped your economy; you have cut subsidies; you’ve opened markets. The challenge is the politics, but in this environment, keep in mind that the NAFTA deal was cut in late 1992 after the elections. Actually, it was cut a little before the elections. The DOHA Agreement or the Uruguay Round agricultural accord was done in December of 1992. So, there’s some history here of doing a framework, and then having cross administrations in the U.S. take responsibility. I personally think that that would be a good idea. THE MEDIATOR (Dr. Irene Klinger): Thank you, Mr. Zoellick. Ambassador Ospina, you have the floor. El Embajador Ospina de Colombia. THE AMBASSADOR OF COLOMBIA (Ambassador Camilo Ospina): Gracias, Presidente Zoellick. En la reunión del Grupo de los 20, se propuso la creación de un sistema de regulación financiera global y de un sistema de verificación global. Había de alguna forma consenso entre la mayoría de los países. Tal vez, Estados Unidos fue el que tuvo la posición de no aceptar esa posibilidad. Sabemos que el Banco Mundial está desarrollando la agenda de lo acordado en el Grupo de los 20 y que en marzo, habrá una nueva reunión. ¿Qué tan viable ve usted esa posibilidad de crear instrumentos de regulación global para los sistemas financieros? THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): If you look at the Work Plan that came out of the G-20 meeting, there was an extensive discussion of work in the financial supervision and regulatory area. I wouldn’t suggest you are going to see a global regulator. I think what is much more likely is that you’ll see efforts of groups like the Financial Stability Forum (FSF), which will add developing country members, the IMF, the VASO, and others, and some of the World Bank’s activities trying to bring countries together on common principles and solve common problems. It wasn’t just the U.S. that was a little cautious on this. In fact, I would actually mention that some of your Latin partners, whom I won’t identify, were a little concerned that some of the European ideas seemed to be so regulatory that they could actually stymie some of the development in Latin America. So, I think this is going to be a mixed effort. There were good ideas from a wide range of countries. For example, in the Brazil meeting of finance ministers, there were all also central bankers present. The Chinese Central Banker made an excellent presentation about the dangers of what economists call pro-cyclical policies. In other words, you can actually have regulatory and accounting policies that deepen the effect of the cycle. Some of this has led to the discussion about what people refer to as “Mark-to-Market” under fair value accounting, and when it becomes “Mark-to-Model,” and when it becomes “Mark-to-Myth”. So, there are challenges on how to make some of these systems work. What I personally am focused on at this point—and this applies to developed and developing economies—is that I’m concerned that governments haven’t yet figured out how they’re going to absorb the losses and bring private capital back into the system. You have had a lot of losses taken by some of the private banks. The governments have inserted money in, in various forms: subordinated debt, preferred stock, and others. I think they are going to have to recognize transparently that a lot of that money is going to have to pay for losses, that it is not a loan and that it is actually going to pay for losses embedded in the system. Otherwise, what private investor would ever put private money back in these institutions? As you saw, this happened with some of the sovereign funds. They put capital in and it was just chewed up right away. So, if you look at the expected losses from a number of these institutions, in some ways I think the government is going to have to be clear with what was referred to sometimes as the “bad bank, good bank model,” setting aside the bad assets and saying we’ll take account of these. And if you look at the rescue for Citigroup, this tended to be a little bit more transparent in that nature. This is another good example—and all of you know this from your public service—sometimes things all move very fast, and governments are trying to keep things liquid and institutions going, but they need to think towards the second and third order issue. In this case, you are eventually going to have to get capital back in these institutions, but people are not going to do it if they feel that they’re just going to lose their capital. So, one of the decisions I think you are going to see governments make over the next four to five months is how they do recognize some of the losses on some of those bad assets. There could be issues related to accounting too where, as opposed to just absorbing the heat, if you have what financers call the “match book” between the assets and liabilities of its duration match, you don’t have to recognize the losses as long as you have the liabilities there. These are some of the tensions on the supervisory and regulatory side. One thing to be careful about—which I’ve seen in the U.S. system at various times, and it’s going to be true globally—is that there is a tendency among regulators to close the bond door after the horse has left. They actually make it harder to deal with the problems by catching them after the effect. I think some of the issues in the financial and regulatory supervision area could fall on that category. However, I’ll give you one other anticipatory topic, which is interesting. When they look at the present crisis, many people say that there was all this liquidity after the Internet boom in 2001, that people didn’t watch this closely enough and that it led to this “lot-of-moneychasing yield,” and this boom, and then bust. Well, if you compare liquidity today with liquidity in 2001, it makes 2001 look like a desert. So, again, you have to think that at some point, the velocity of money will pick up, and when it does, central banks are going to have to be in a position to withdraw some of their liquidity. You also have to make sure that the banking supervisors don’t repeat the mistakes of the past, because you could get an even bigger boom bust, looking three or four years out if you are not careful. THE MEDIATOR (Dr. Irene Klinger): Thank you very much. I have a question from the audience here in the third row. Please, if you can introduce yourself, sir. THE AUDIENCE: Yes, I am Roberto Jiménez Ortiz. I am from El Salvador and a former Bank Executive Director (ED). Two questions for the President. First, during the 1997 Asian crisis, the Bank was unprepared and didn’t know it was coming. The same happened five years before with the tequila crisis. Now, how well prepared was the Bank for this crisis, especially to the financial system in Latin America? My second question refers to the governance issue in the World Bank. As you may know at the G-20, one of the issues in the Bretton Woods Project is the reform of the Bank. As you know, the Board of the Bank is dominated by the G-20—by the G-7, maybe by the G-5, I would say—and Latin America needs more voices there. What would you recommend from your point of view as one of the brokers there? What kind of governance proposals would be willing to go through? And lastly, given that you have some Fannie Mae credentials even if from 20 years ago, you mentioned something about derivatives. In reference to derivatives, Wall Street now is a little nervous about them. What are derivatives? Are you trying to get a new instrument in the Bank? Can you explain this to us? Thank you. THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): There are a lot of needs to those questions. In the first one, I think one area that I was pleased about and on which we were a little ahead of the curve is the food and fuel crisis. I was watching the food crisis starting to increase and was challenging some of my economists to run through the implications of this. Not surprisingly, at first many people looked at it in aggregate. They said that this would help countries that have commodities and that they’ll get more revenue. And I said that it is very important to disaggregate, because even with a commodity-producing country, the poor may get hurt. So, we moved quite quickly, and I was trying to support the U.N. agencies with some of this rapid financing facility and drawing attention to the need to support the U.N. World Food Program, which needed to go from about $3 to $6 billion. On the full scope of this financial crisis, I don’t think that anybody could anticipate exactly what we have encountered. All during the course of the year I could see that it was going to be particularly challenging. What I tried to do at our annual meeting in October was to identify that the events of September and October, in my view, pushed us into a new level. In that sense, we tried to use the meeting to point out to people—and I tried to use forums like this to do so—that I think we were going to be in a difficult space for 2009, and perhaps beyond. Your second question is about voice and accountability. Let me give you some of the basics on this. We obviously have to work with our shareholders. Management can do things like change the composition of our staffing, so I have appointed eight officers—seven of them are from developing countries. My first Chief economist is from a developing country, but in addition—and you are right—we can try to bring our shareholders together. In fact, we took a first step this autumn as, frankly, the region that was most poorly represented on the Board was Sub-Saharan Africa. We have 24 chairs and we agreed to add one for Sub-Saharan Africa, because we only had two for that region, so we will add a chair for Sub-Saharan Africa. In terms of the voting, we have adjusted the voting a little bit, so the share of developing countries is now up by 44%, and for IDA up to 48% of the total. The number of chairs now on our Board has a majority of developing countries, but here is where the challenge comes in. You have to figure out the balance among what. If you did it on size of the economy, the U.S. would actually have a greater share, because it actually has 17% of the vote, and it’s bigger as a percentage of GDP. And then you would have to decide if you did it only on the size of the economy, then some of the African or Caribbean countries would have no representation, and that wouldn’t be right. So, how do you get that balance among those various interests? What I tried to do while taking this first step was suggest that we need to take more steps. To give us an independent view, I have asked former President Zedillo to chair a governance group to step back—and actually, we’ll again have more members on this commission from the developing world than the developed world—in order to look at some of these issues over the course of the coming year. Now, there are other issues, and I’ll just give you some of the tensions involved with this. Of the 24 current chairs, eight are from Europe. Now, Europeans often talk about improving governance, but they don’t talk about giving up any of their chairs. To be fair to them, when it comes to IDA—and your colleague from Paraguay asked about IDA—the Europeans are pretty generous contributors. One of the problems with this balance is that if you take the Nordic countries, for instance, they have been pretty good contributors. They would really like to have a chair, and it’s hard for them to get the money if they don’t have a chair that at least represents the Nordic and Baltic countries. These are the balances that you have to have. Should the chairs represent the size of the economies, the size of the economies plus some special representation for the poorest? Does it matter whether countries contribute to some of the special programs we have for the poorest? How do you get that interconnectivity? I will say this: there aren’t many decisions that actually go to our Board by voting, and so, I do think the main thing is making sure you have the participation in the discussions and in the day-to-day process. Now, there’s another big question that I do think people have to ask. It is a little strange to have a full-time board. I’m sure Luis Alberto Moreno will talk to you about this from the Inter-American Development Bank standpoint (IDB) as well. Our direct expenses for our Board are $70 million a year. I just did a review using 365 days a year, and we produce 17 papers a day for that board. You have a board that was created before the era of air travel and, to be honest, one of the questions one should face is: Does that make sense for this period? There are benefits of it. You do have greater interaction, but you also have drawbacks. So, those are some of the questions that Dominique Strauss-Kahn, President of the International Monetary Fund, asked a commission that is chaired by Finance Minister Trevor Manuel of South Africa to address, and I’ve asked President Zedillo to do the same with another commission. Regarding your third question on derivatives, let me just say this, and this is the last thing on the financial crisis. When I was at the G-20 heads’ dinner, Mario Draghi, Chairman of the Financial Stability Forum, talked about making securitization work again, and one of the heads of government said that this was terrible. To be honest, you are not going to make the financial system work in many countries unless you get securitization working again. One of the problems now that people talk about is the fact that banks in the U.S. are not lending. They are actually lending, but they don’t have the ability to remove the product from their books, so you have got to make securitization work. In reference to derivatives, they are a form of securitization. Let me give you an example of why they can do so many good things. We are using weather derivatives. Because agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa is primarily based on rainfall, if the rainfall doesn’t reach certain levels in a country like Malawi, we will give special payments to the farmers in that country. This has already been done with the U.N. World Food Program where they have to manage currencies, prices, and other uncertainties. We are trying to help them improve their risk management, and we figured they could probably get 20% added efficiency. So, I don’t think that you want to end all derivatives. I think that there will be lessons, as was the case with some of the credit derivatives. You have to have clearing houses and settlement mechanisms to make it work better, and there are issues related to the supervision of how institutions use derivatives, but I don’t think you want to throw out the baby with the bath water. THE MEDIATOR (Dr. Irene Klinger): Thank you very much. I’ll have to take the last question, because Mr. Zoellick has to go. Embajador Efraín Cocíos del Ecuador tiene la palabra, pero le ruego ser breve. Gracias. THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): I could have answered more questions, but your ambassadors are trained to ask multiple questions. It must be the way the Secretary General runs it. [Laughs.] THE AMBASSADOR OF ECUADOR (Ambassador Efraín Cocíos): Muchas gracias. El señor Bernard Aronson, en el transcurso del diálogo con el señor Zoellick, cuando se refirió a lo que él llamó el surgimiento de algunos populismos en América Latina, dijo que estos presuntos gobiernos populistas –presuntos, es mi afirmación– están propugnando la tesis de “más Estado y menos modelo libre”. Obviamente, la respuesta del señor Zoellick fue exactamente que lo correcto sería dar una respuesta con más “modelo libre mercado” y menos “Estado”, es decir, más inhibición del Estado en los problemas. Entonces, aquí la pregunta que cabe es la siguiente: ¿Cómo así tuvo que intervenir el Estado en los Estados Unidos para salvar a los bancos y al sistema financiero en general y no se dejó al libre mercado que solucione la crisis? Gracias. THE PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD BANK (Mr. Robert Zoellick): I think you are making a debating point that is a parity of what I said. I said that the countries that have done better in Latin America have been ones that have tried to adapt to market needs in terms of their fiscal policies, their monetary policy, and some of their currency flexibility. That is just a fact. We can debate policies, but it is a little harder to debate facts. In terms of government intervention, as I said, my view on this has always been of a pragmatic one. I know the history of my own country’s role with government intervention throughout the 19th century; some of it was done by the State level. As I said in my answer to Bernie, you have to understand the pros and the cons of this. So, there’s the danger that the government starts to control investment or control companies. For example, this was what was done in the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact states, and it didn’t work very well in that more extreme model. And then, we have seen in Latin America models where you had favored oligarchies and oligopolies. It worked out very well for those who were the favorite people, but it didn’t work out very well for those who were left out of the system. When I used the examples of Brazil’s Development Bank, Mexico’s Development Bank and others, I also said that there is obviously a very important role for some of those State institutions to play, but each society has to figure out how far it wants to take it and whether at some point it can interfere with some of the possibilities for private investment. As I talked about infrastructure, I mentioned how you create various public-private sector models, but let’s even go much more basic. There’s a fundamental role for the State in determining property rights, contracts, rule of law, and enforcement. Then, beyond that, it’s up to various polities to decide how much they want the government to intervene, whether they want them to control natural resources. Frankly, from the perspective of the World Bank, what we try to do is show different experiences out there. We had a growth commission that was chaired by Michael Spence, a former laureate of the Nobel Prize, which drew together people from all over the world, scholars, public officials, and others. The basic message was that there are very few countries—you really can’t find any—that grew if they didn’t have openness to international markets. Some of them were more open on the export side than the import side for a period, but even that had to change if they wanted to be able to get lower-cost inputs. Investment in their citizens was very important, and education, basic social welfare, as well as building the foundations became very, very important. There clearly was a key need that if the government was involved, it did so in a transparent way to try to reduce the dangers of corruption and favoritism. There are different models out there, and one of the benefits, I hope, in democratic systems is that people can help select those models, to be able to choose from. You can see what has been done well in East Asia, and you can see what has been done in Western Europe. Again, I’ll just take another region, Sub-Saharan Africa. When I go to Sub-Saharan Africa now, which has been growing pretty well—if I might add—over the past ten years, but also faces dangers from this crisis, I am struck by the fact that what I hear coming out of that region is probably what you would have heard from Europe fifty years ago. People want energy; they want infrastructure; they want regional integration linked to global markets; and they want healthy private sectors, particularly for some of the smaller businesses to be able to get going and create jobs. In some ways, there are some basic principles, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t have government interventions, particularly in a period like this one where you’re going to need to have your central banks and also, as I said, you need to have a good fiscal response at present if you can afford it. But this is where the devil is in the details. The United States is very fortunate as it can have a very big fiscal expenditure and, frankly, the U.S. dollar still goes up. For some of the countries represented in this room, it’s not so clear that they can do that. And so, you need to know the pros and cons of any of the actions, and partly what we try to do as an institution is make countries available aware of what their choices are, and what the experience has been. However, ultimately—and this is a key point to which the Bank was moving to before I got there, and one that I certainly endorse—no development program works unless you have national ownership. It must be owned by people, and they must have their own sense that they have control over their future as best they can in a globalized environment. So, what we try to do is help them make informed choices, and then, it’s up to them and their representatives in government to make them and to stand by them with the public. [Applauses.] THE MEDIATOR (Dr. Irene Klinger): Muchísimas gracias, señor Zoellick y también señor Bernie Aronson, por este excelente diálogo en la tarde de hoy. Justamente, esto era lo que pensaban nuestros Embajadores, Representantes Permanentes ante la OEA, cuando plantearon la idea de llevar adelante la Cátedra de las Américas para fomentar y fortalecer el debate hemisférico sobre los temas que aquejan al Hemisferio Occidental y al mundo en general. Les agradezco por haber contribuido en este proceso. Quisiera también agradecer a la Universidad San Martín de Porres, representada aquí por el señor David Cunza que ha sido nuestro socio en este esfuerzo durante todos estos años, así como a aquellos que nos han apoyado en algún u otro momento, como la República Popular China, Francia y España. Asimismo, quisiera agradecer a aquellos que transmiten la Cátedra de las Américas, que la difunden a través de satélite, como son la Voz de las Américas (VOA), la Red Internacional Hispana de Televisión (HITN TV) en los Estados Unidos, EDUSAT de México, Venevisión Continental y varias cadenas de radio y televisión que llevan la señal a los Estados Miembros de la OEA, así como a través de Webcast. Quisiera agradecer a la audiencia aquí, a todos ustedes y a todos aquellos que nos escuchan a lo largo y ancho de nuestro Hemisferio e invitarlos a la Trigésimo Segunda Cátedra de las Américas, que tendrá lugar el 12 de enero 2009, con la participación del Presidente Luis Alberto Moreno del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID), en la cual cuando podremos seguir discutiendo temas de importancia para nuestro Hemisferio. Muchísimas gracias a todos.