Endpoints of Resuscitation: How Much Is Enough?

advertisement

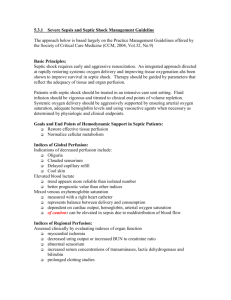

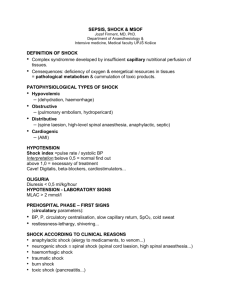

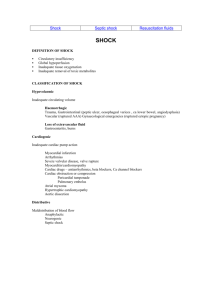

Shock is the clinical manifestation of inadequate tissue perfusion secondary to circulatory collapse. Shock can be grouped into four groups, based on etiology: hypovolemic, cardiogenic, obstructive, and distributive. The first three groups are characterized by low cardiac output. Distributive shock, which encompasses sepsis and anaphylaxis, is usually a problem of the periphery, with high cardiac output and very low systemic vascular resistance. Treatment of shock is dependent on the underlying pathology, but end organ perfusion remains the goal of therapy. Current guidelines recommend a combination of MAP, CVP, urine output, lactate, and central oxygen saturation to determine effectiveness of resuscitation. We will discuss the current guidelines, review the pathophysiological basis for each endpoint, as well as touch on ongoing controversies within this field of study. The primary goal of resuscitation in shock should be restore adequate tissue perfusion, and therefore, cellular metabolism (1). Although the mechanisms behind shock are varied, initially resuscitation is problem based. Therefore, a patient with severe pneumonia and one with tamponade both face issues with tissue hypoperfusion, but with very different etiologies. Identification of tissue hypoperfusion is very important, as is monitoring effectiveness of therapies. The landmark study by E. Rivers in 2001 introduced us to early goal directed therapy, and the resuscitation end points utilized. His team included mean arterial pressure (MAP), central venous pressure (CVP), central venous saturation (ScvO2), urine output, and oxygen saturation as the endpoints of resuscitation (2). These endpoints were chosen due to evidence supporting their role in monitoring global and molecular oxygenation, although there are benefits and caveats for each one. The use of these endpoints has been widely accepted by critical care (3), and has been studied as a prognostic marker as well as an endpoint (4). Although there has been improvement in outcomes in patients with severe sepsis, circulatory shock continues to have a high mortality. Septic shock is characterized by a derangement of microcirculation, something not necessarily seen in other forms of shock. Ongoing research is centered on evaluation of these endpoints, and the relationship of oxygen consumption, delivery, and tissue perfusion. For example, lactate has long been used as a marker for tissue perfusion, but concerns regarding clearance in the face of renal and hepatic dysfunction, as well as epinephrine induced elevations, have led many to question its utility as an endpoint (4, 5). Furthermore, there is ongoing debate whether we are targeting the correct thing; whether pressure is equivalent to flow, or if lactate is truly a measure of metabolism, or if lactic acidemia is merely an epi-phenomenon (5, 6). 1. Vincent, Jean-Louis, DeBacker, Daniel. Circulatory Shock. NEJM 2013; 369 (28): 1726-1734. 2. Rivers E et al. Early goal directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. NEJM 2001; 345 (19): 1368-1377. 3. Dellinger, R et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013; 41 (2): 580-637. 4. Jansen, Tim C et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2010; 182: 752-761. 5. Bakker, Jan et al. Clinical use of lactate monitoring in critically ill patients. Annals of Intensive Care 2013; 3:12. 6. Dunser, Martin W et al. Re-thinking resuscitation: leaving blood pressure cosmetics behind and moving forward to permissive hypotension and a tissue perfusion-based approach. Crit Care 2013; 17:326.