Questions from Liberalism Readings

advertisement

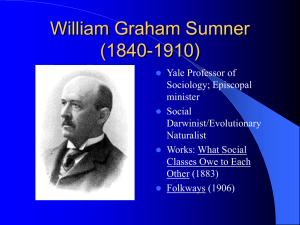

Questions from Liberalism Readings 1. Hobbes On pp. 57-58, Hobbes outlines three principal reasons why he thinks conflict in the state of nature is inevitable. These are "competition," "diffidence," and "glory." What does Hobbes mean by these terms, and why does he think they will inevitably culminate in "war," as he understands that term? 2. Hobbes Hobbes has often been accused of having too negative a view of human nature in the state of nature and, consequently, of rushing too quickly to the notion that people would accept an absolute ruler so long as it provided for their safety. On p. 58, he offers what he hopes will be an empirical proof of his theory of human nature, by describing the behavior of people who actually live in political society, which he imagines to be much safer than the state of nature. What examples does he give to "prove" his theory? Do you find them convincing? By way of updating this argument, we might think of the debate over security versus individual rights in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Do you think most people would opt for greater security, even if it meant a diminution of individual rights? Should they? During the Age of Enlightenment, many philosophical figures rise to the occasion of political struggles and offer their perspectives with varying issues. One of the greatest political works produced during this period of time is Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes maintained the belief that people contradict state of nature where people under human nature, enter into a social contract, in which the people grants the power to act on their behalves to those in greater power, in exchange for safety and protection. However, Hobbes believes human nature to be in continuous struggle because of their desire for power. The struggle for power in turn fuels the endless conflict to obtain power and dominance. As described by Hobbes, the fearful then enters the social contract, giving ways to absolute ruler for survival by any means. This general fear is again experienced by the people in the wake of 9/11. On September 11, 2001, the people of United States had fear reined over them through terrorist attacks on American soil. Following the events of 9/11, congress enacts the USA Patriot Act of 2001. As a response to the terrorist attacks, congress expands the power of protection and as a result, severely limits the individual rights of the citizens and people in America. The Act is signed into law by President George W. Bush as a response to reduce the restrictions in law enforcement agencies to collect vital information to prevent future terrorist acts. Despite of the government’s interest to protect the citizens, major concerns to privacy rights are being raised. To this day, people have engaged in various forms of debate in regard to this issue. Yes, it is the government’s responsibility to ensure the safety of its citizens; however, it should not come at the cost of diminution of individual rights. From the perspective of the law enforcement agencies, it is absolutely necessary for them to assume complete authority over the people in order to provide the essential security and protection which the people seek. The people have also responded that the expanded power and reduced restriction are convenient, but not at all absolutely necessary. And the people should fight to maintain their individual rights. After all, these rights are specifically stated in the US Constitution. Any bypass of the individual’s constitutional rights is a trespass against the beliefs of the Founding Fathers. If people are to surrender their individual rights—even if it is to provide for their safety—human nature dictates that those in power will only seek for more power. People should not succumb to the temptation of safety under absolute ruler and surrender their individual rights. As the US Constitution to be the pillars of this nation, removal of these pillars and the result will be the collapse of an entire nation. 3. Locke In A Letter Concerning Toleration, Locke gives a number of reasons why state power (or the "civil magistrate"), should not be understood as having any say in what religion people should follow. What reasons does he give for this? Similarly, Locke adduces a number of arguments in favor of the notion that a church should best be understood as a voluntary association. What are they? How far should they be understood as limiting any church's power? What legitimate or justifiable powers does any church still maintain over its members, according to Locke? 4. Locke What is the importance of the development of money for Locke's argument about the extent of property accumulation in the state of nature? What are the consequences of his argument from the standpoint of economic equality? Does Locke think this will be a problem? Why or why not? Labor creates property with limits to accumulation. Locke believes that there should be limits to accumulation of property but with the introduction of money, that makes accumulation of property unlimited. He is aware of the problem and acknowledges it because one can only have what can be used before spoiling; having more creates waste and is an offense to nature. However he does not specify which principles government should apply to solve the problem. 5. Paine According to The Rights of Man, what is the rationale behind Paine's claim that only the present generation has any claim on the politics of today? Do you find this argument convincing? Why or why not? Paine claims that only the present living people, the present generation, has any claim on politic of today because first of all, it is them that are being “accommodated.” This means the politics caters to their wants and needs and not those from the past so they are the participants and concerns of their politics. They have the authority to direct the politics in which ever direction they so choose including how it is organized, administered, or functioned. This argument is very convincing to me as I agree that we, in our current time, define the ways in which politics works to our favor. Those in the past may have helped form foundations but the present day politics is formed by the interests of present day people. And seeing how interests change with the passing of each generation, it is clear that politics too changes with time. 6. Declaration of Independence What are the specific grievances listed by the colonists in The Declaration of Independence? How might one read these grievances from the perspective of liberalism? How might one read them from the perspective of republicanism? The grievances expressed in the constitution are the suspension of various law-making abilities, the lack of proper representation in the English government for taxation and other actions, the disbandment of local representative bodies, the suspension or ignoring of local law, the appointment of various government officials, the housing of soldiers in the colonies houses without consent, the regulation of trade, and the general material damage done to the colonies in the pursuit of these things. A liberalistic reading of the Declaration of Independence would stress the grievances, and cast them as violations of the “inalienable rights,” or the guaranteed freedoms, of all “Men.” On this reading, the colonies are justly revolting because of the “tyrant,” the ‘bad guy,’ the English government has formed itself into by these actions; the English government has committed many grievous ethical violations by these, which all, in essence, are suspensions of freedom – that which is tantamount to the suspension of the possibility of a “pursuit of happiness” under a liberal reading. The suspension of certain privladges of trade, for example, would be cast as the inability of a man to make his livelihood because of the will of the English government, a decision made without contract from the man, without proper consideration and compensation. A republican reading would hold that because “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” the English government implicitly forfeited its right to govern over the colonies, as the “Men” which the government, by its nature, consists of are not “among” the “Men” of the English government. Rather, these “Men” which are in their constant the substance of government reside in local governing bodies, so the “Declaration of Independence” is primarily informative with spirited rhetoric – something like, by the nature of government we now govern ourselves, and you are bad, bad government for impeding this, trying to substitute this, without meeting certain conditions – rather than the document of revolt and blame many of us understand it as. 7. Declaration of Independence If you were part of a group whose members had been systematically denied the rights that Jefferson sets forth in the Declaration, how might you go about arguing for inclusion? What does the Declaration suggest is the appropriate response to government if such rights are continually violated over a long period of time? 8. Declaration of Independence In the final, seldom-remembered list of complaints about the behavior of King George III, the Declaration discusses Native Americans. What does it say about them, and what does this say about the history of liberalism? 9. Declaration of the Rights of Man Which article of the Declaration most clearly attacks the notion of ascribed status and aristocratic privilege? Why? 10. Declaration of the Rights of Man Which articles of the Declaration most clearly attack political absolutism? Why? The article that most clearly attacks political absolutism is #3 where it essentially states that France shall have no leader or group of leaders with absolute power or any power that is not granted from the state itself. Essentially it prohibits kings or any absolutist type of leadership. It also ends the idea of divine right by saying sovereignty is granted by the State. Also #14 states that political absolutism cannot exist because all citizens have a voice either directly or indirectly. 11. Smith Smith argues that, in addition to the natural propensity to truck, barter, and exchange, there is another feature of human life that separates us from animals. Do you think there is sometimes a tension between these two elements of human existence? Why or why not? 12. Smith In a fascinating argument that is all too often overlooked, Smith maintains that, "The difference of talents in different men is, in reality, much less than we are aware of." He goes on to add that while it may offend the "vanity of the philosopher," the fact is that: "By nature a philosopher is not in genius and disposition half so different from a street porter as a mastiff is from a greyhound" (p. 90). On Smith's account, then what accounts for the "very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions" (p. 90)? 13. Kant Kant gives two broad sets of reasons why individuals have not heretofore thrown off their immaturity. What are they? 1. Laziness: it’s easy for people to just have others do their thinking for them and warn them of what they believe is dangerous. 2. Cowardice: People fear thinking for themselves after years of infantile dependency. 14. Kant To what extent does Kant believe any generation can legitimately limit the willingness of future generations to dare to know? Which institution does Kant use as an example of one that might well attempt to engage in such behavior, and what does he think of it? 15. Mill Mill famously declares that: "If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind" (p. 97). Mill gives three basic reasons for this claim. What are they? Do you find them convincing? Why or why not? 16. Mill On pp. 98-100, Mill insists on the fundamental importance of individual eccentricity for democracy, especially among those whom he calls "geniuses." This argument seems strange. Why are eccentrics so important in a democracy, according to Mill? 17. Mill Unlike many of his contemporaries, Mill was far more consistent in the application of his liberal democratic principles. For example, he advocated extending the suffrage not only to the working class, but also to women, and was a committed opponent of slavery. However, it also must be noted that Mill was an employee of the British East India Company, the central tool of British imperialism on the subcontinent, and consistently maintained that neither liberty nor democracy were applicable in less "civilized" parts of the globe (like Asia). In such places, he claimed: "Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided that the end be their improvement, and the means justified by actually effecting that end" (p. 95). What reasons does he give for this position in the piece we read? 18. Sumner At the beginning of this piece, Sumner argues that "every man and woman in society has one big duty." What is that duty, according to Sumner, and why would it be a fundamental mistake to try to go beyond it? 19. Sumner The key figure in Sumner's analysis is the one he calls "the Forgotten Man." Who is this individual? How and why is he forgotten? Why does Sumner believe that the case of the Forgotten Man illustrates the problem of enabling government to do more than protect the persons and property of its citizens? “The Forgotten Man”, defined by William Graham Sumner, is a person of group of people that is treated with neglect and basically forgotten. He describes it as someone who is worth, industrious, and self-supporting yet at the same time neither poor nor weak. In conclusion, the “Forgotten Man” is part of the working class. Sumner uses the example of a drunkard who is in the gutter. As we pass by we develop a feeling a pity towards him. Yet when we see a policeman picking him up, we say that society, using the policeman, saved him from his suffering. Now the workman who paid the wages of the policeman is the “Forgotten Man,” since he never gets noticed and is passed by since he did his job honestly, without complaints. According to Sumner, “Consequently the philanthropists never think of him, and trample on him…” Since the Forgotten Man is unfortunately neglected, Sumner believes that this causes a sense of loss and waste from the government. 20. Green Green makes a radical break with many classical liberals, like Locke, who argued that the right to property was a natural or pre-political right. That is, for Green property rights are not sacrosanct emanations from natural or God-given law that government must never infringe upon. How does Green go about defending this claim, and do you find it convincing? Why or why not? Green defends the idea of property rights by that ownership is crucial to the right of pursuit of happiness. Green stresses the right of individual lawn ownership by defining it necessary for the development of the individual’s ethnics. The last defense that Green states is that individual should have land to be used as they please. I find Greens defense convincing because land ownership does the teach the individual the ethics of pride and responsibility which today is crucial to survive in the outside world. 21. Green Green argues that the ancient republics of Greece and Rome were ultimately inferior to modern industrial societies, even with all the problems of the latter, because they were built on slavery. They were states in which "the elevation of the few is founded on the degradation of the many" (p. 106). Moreover, Green claims that this is not only true of involuntary slavery, but voluntary slavery as well: "We condemn slavery no less no less when it arises out of a voluntary agreement on the part of the enslaved person. A contract by which anyone agreed for a certain consideration to become the slave of another we should reckon a void contract" (p. 107). Now, at least one highly influential neoclassical liberal, Robert Nozick, defended the justness of voluntary slave contracts in his celebrated book, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974). Why does the welfare liberal Green reject voluntary slave contracts? Why might some neoclassical liberals or libertarians like Nozick defend them? Should people have the right to voluntarily enslave themselves in a free society? Why or why not? According to Green freedom is not something that can be had by the cost of the loss of the freedom of others. Further, free society is the construct by which possessions are guaranteed. If members of society become possessions by contract whether by compulsion or voluntary it is anathema to the concept of freedom. Nozick and other neoclassical liberals and libertarians will argue that in a free society, dictating the extent of ones freedom is in and of itself a diminishing freedom. Everyone has the right to do as they please so long as it does not harm others. Although I believe society needs to be protected by it's government, I do not believe it has the right to interfere with someone’s right to "enslave themselves" as Green says. Diminishing someone's freedom because we feel their decision is bad for them is not freedom at all. 22. Green At the conclusion of this piece, Green maintains that "we shall probably all agree that a society in which the public health was duly protected, and necessary education duly provided for, by the spontaneous action of individuals, was in a higher condition than one in which the compulsion of law was needed to secure those ends" (pp. 107-108). Nevertheless, Green does not believe this will happen; therefore state intervention is absolutely necessary to achieve these ends. What reasons does he give for this failure? Are his reasons historically convincing? Why or why not? 23. Roosevelt Roosevelt argues that, in various ways, the opponents of the New Deal have been "deceitful." What examples does he give to justify this assertion? 24. Roosevelt What sorts of programs does Roosevelt single out as essential ones for the continuation of the New Deal in his second term? How are these programs illustrative of the welfare liberal conception of "positive freedom"? 25. Allen Throughout this essay, Allen compares current debates about censoring and making illegal certain types of speech and behavior to the Prohibition movement. On Allen's account, what lessons should we learn from the failures of Prohibition that are applicable today? 26. Allen What is the fundamental difference between Allen's understanding of the importance of individual liberty for democracy, and that set forth by J.S. Mill? Put differently, why isn't Mill a modern libertarian like Allen? Or is he? J.S. Mill’s view on the importance of individual liberty is the most important part of any government. He believed that a person should have control on how they thought, and the actions they took. He said that they should do so as long as it doesn’t affect another person. Allen on the other hand believed that a person’s individual freedom was more important. I would offer that they are somewhat similar to each other. Most would argue that freedom and liberty could mean the same thing, and I for one attend to agree. Therefore, Mill’s could be looked at as a modern libertarian like Allen. 27. Rothbard Despite the fact that libertarians take some positions generally associated with the political left wing, and some positions associated with the political right wing, Rothbard does not believe that they are confused. Indeed, he argues that libertarianism is the only truly consistent variant of liberalism as an ideology. Why? 28. Rothbard Why, precisely, is the regulation or restriction of free speech, or the outlying of pornography and drugs by the state, a form of "aggression" on individuals? Is preventing people from doing something the same as attacking them? Why or why not? The restriction of free speech, and outlying of drugs and pornography may not present an immediate physical threat but still applies the threat of forceful action against the individual if he/she does not cease their behavior and/or actions which in Rothbard’s eyes are “victimless crimes”. Later action can always include physical detainment and incarceration. The idea of preventing someone from doing something cannot be seen as an “attack” because there are ways to prevent someone from doing something other than by means of violence like talking to the person instead and circumstances must always be taken into account. However, the more intense and severe the means of prevention become, the thinner the line between dissuasion and aggression becomes. 29. Rothbard At the conclusion of his essay, Rothbard argues that land and animals should be understood originally as unowned "resources" that can legitimately become the private property of individuals. How does this process unfold, according to Rothbard? How does it hearken back to Locke's arguments? Is his argument about what makes "resources" into private property a convincing one? Why or why not? At the conclusion of his essay, Rothbard argues that land and animals should be understood originally as unowned "resources" that can legitimately become the private property of individuals. How does this process unfold, according to Rothbard? How does it hearken back to locke's arguments? Is his argument about what makes "resources" into private property a convincing one? Why or why not? According to Rothbard, Unowned resources such as land and animals are given, to all humans, equally. And that no one should have privileged access to these resources. And, Rothbard also says; that any man who works on this land, or domesticates these animals, for the production of goods or the advancement of humanity. Should then, by this law, be granted ownership of these resources. He believes that this is the undeniable law of nature and should be observed by every person on earth. This is similar to Locke’s ideas of how every man is entitled to property and the freedom to do with it what he chooses, as long as it does not infringe on another mans liberties. And that that freedom is, according to Locke, God given (or as Rothbard puts it, Given by nature). And that no earthly authority, or state, can invade those rights.The fact that someone can obtain ownership of such resources, though the “taming” of them, is a legitimate statement. Because these resources, in a way, belong to everyone. And whoever takes the time and dedication to domesticate these resources, for the use of all mankind. Is righteously using them and deserves, by that right alone, to take ownership. 30. Ball Why does Ball think "Marketopia" is unfair? Do you find his argument convincing? Why or why not? 31. Ball There does not seem to be anything inherently unfair about treating your professors as "service providers," and seeing yourselves as "costumers" partaking of their services. Nevertheless, Ball still seems to think there is something wrong with this model. Why? Do you agree with his argument? Why or why not?