History - Edward Pawn or Elder Statesman March 1997 Article

Issue: 27 | March 1997 | Page 38-42 | Words: 3949 | Author: Christmas, Matthew

Edward VI

Pawn of elder statesmen or, as Matthew Christmas argues, another Henry VIII in the making?

Historians, teachers and students do not tend to give much time to Edward VI. The legendary late Professor Elton gave his short reign 12 sides in his 492 page book, England Under the

Tudors , and few main stream A-Level textbooks do much more. Can one blame them? After all,

Edward was a sickly child, -clever, oh yes, but he never ruled. He was probably irrelevant and at best a puppet of the more interesting Dukes of Somerset and Northumberland. Elton indeed goes even further in the damning of the boy into obscurity: 'self righteous, inclined to cruelty and easily swayed by cunning men, he exercised such little influence as he possessed in favour of disastrous policies and disastrous politicians.' In fact, he claims that 'he reduced the kingworship of the early sixteenth century to absurdity... the crown was never quite the same after

Henry VIII died.' Latimer was right then, when he preached before the minor in 1549 using the words of the Book of Ecclesiastes: 'Woe to thee, O' land, where the king is a child'. Historians should pass on to consider the effectiveness of the 'real rulers' and whether 1547-1553 was part of a time of crisis.

However, now is the time to pause and consider the issues in more detail. This article will suggest four hypotheses. It will firstly show that the boy who became a young man was not only highly educated, but also intelligent and ruthless enough to apply to the business of government the lessons of what he was taught; secondly, that as the reign progressed and with the fall of

Somerset, he was increasingly important and involved in what was done in his name (indeed, even the Lord Protector ignored him at his peril); thirdly, that on dying less than four months before coming into his majority at 16 he was on the verge of taking full power; fourthly, that it was Edward just as much, if not more, than Northumberland who was the author of Mary

Tudor's exclusion in favour of the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey. Edward VI may well have surpassed his own father, the infamous Henry VIII, as a king who would brook no opposition.

A promising school report

After those oft-quoted words from the Old Testament, Latimer rapidly moved on to preach on another text, 'Blessed is the land where there is a noble king' and proceeded to apply this by cataloguing Edward's virtues: the realm of England was, indeed, fortunate. One can dismiss the verdicts of Latimer, Sir Anthony Cooke, Roger Ascham, John Foxe ('a Prince, although but tender in years, yet for his age and mature ripeness in wit and all princely ornaments, one can see but few to whom he may not be equal, so again, I see not many, to whom he may not justly he preferred') and others as flattery, customary over-the-top panegyric or even Protestant wishthinking in the reign of Bloody Mary. Or one can consider if Sir John Cheke, the young Regius

Professor of Greek at Cambridge, and Edward's other tutors did not, in fact, have a point.

Holbein's picture of the young Prince aged about one depicts Edward resting on a velvet draped panel, on which the Latin text commands him to be like his father. In his later portraits, Edward looks the spitting image of the great Henry. After. all, had not the fifty- eight year old Primate of

All England, Thomas Cranmer, at Edward's triple coronation in February 1547, addressed him as 'God's vicegerent and Christ's vicar within your own dominions'?

The business of making a king was a serious one and no expense was spared. Edward had the best teachers and became fluent in Latin, Greek and French, as well as being a finished scholar

in History and Geography and accomplished on the lute, in the chase and at the butts. Richard

II had become king aged ten in 1377 and at a mere fourteen years of age had personally confronted the Peasants' Revolt and sent the rebels home. Edward VI was expected to rule as soon as possible, despite as a boy of nine stopping his coronation procession to watch an acrobat performing in the street. This may be hard for the twentieth century to accept, but the serious student must do so, just as Edward's courtiers did - with the exception of his uncle,

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset. When the crunch came he paid with imprisonment and ultimately his life.

But surely, all would have paid mere lip service to a weakling, sickly child? This myth demands explosion. Edward was perfectly healthy; although slender of frame. His first of only two major illnesses is recorded by him in his Journal entry for 2 April 1552: 'I fell sick of the measles and the smallpox'. Within three weeks he was better and presided at the Garter ceremony on St

George's Day, 23 April. It may have damaged his health, but it was not until February 1553 that he fell victim to the pulmonary tuberculosis which killed him within five months. It was not until the doctors pronounced that he had only two months to live that thought was given to a different regime. None of Edward's courtiers and officials, not even the powerful Duke of Northumberland, could have hoped to continue in Edward's favour when he assumed power aged sixteen on 18

October 1553 if their actions were not in tune with the King's wishes. Many historians seem to have overlooked this basic reality of power in the tiny world that was the Tudor State. Edward may not ever have had the full, unfettered powers of a king, but his influence should not be assumed to be insignificant. Moreover, it grew and grew.

It is important at this point to mention Edward's scholarship as it does not merely represent what might have been. As well as some school-boy exercises in the French language and over a dozen 'orationes' or declarations on a number of diverse subjects, Edward has left us an important and unparalleled collection of documents in his own handwriting - perhaps more than any other Tudor. In addition to a host of letters to a variety of key figures in Court and Council,

Edward wrote seventeen political and state papers from 1551 to the end of his life, many of which were delivered to the Council, as well as a substantial Journal or Chronicle from the beginning of his reign, with the entries from March 1550 being almost on a daily basis until the end of November 1552. Professor Jordan was of the opinion that the Journal was a unique document in early modern history and commented that it was in many cases the major or even only source for aspects of our knowledge of not only events but also the workings of government in this period.

Despite being sidelined by Somerset, therefore, from the age of about twelve-and-a-half Edward was clearly taking a close interest and an increasing part in government. To take a few references almost at random, his Journal covers subjects such as trade (22 September 1550), payment of the king's debts (10 October 1550), foreign policy (30 May 1552),defensive fortifications (10 March 1551), marriage policy (19 July 1551) and the state of the coinage (6

May 1551). He was clearly well-informed and involved. Critics will still, no doubt, dismiss

Edward's role, but was he not during the time of Warwick's ascendancy from around February

1550 more active as a king than Henry VIII had ever been in the early years of his reign, with his well attested indolence and sheer indifference to public events?

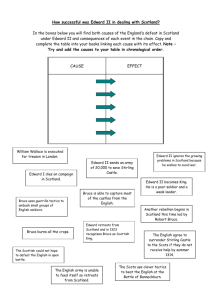

Clearly then, Edward had the potential and interest to rule, but what of the claim that he actually took a real part? Was the Journal not merely part of his education and his political papers just essays in sixteenth-century work experience? There is no doubt that Somerset took advantage of his close blood relation- ship to Edward and of the boy's age to ignore him as much as possible. Indeed, Somerset's undoing was that, in addition to failing to solve many of the problems inherited from Henry VIII as well as causing others, and failing to handle the rebellions of 1549, worst of all he ruled without reference to the other Regency Councillors appointed in

Henry's will, having acquired the power in spring 1547 to appoint new Privy Councillors and dismiss others. It is not surprising then that Somerset treated Edward with disdain in Whitehall,

leaving him with little money and a reduced Household under the control of Sir Michael

Stanhope, his brother-in-law, whilst he ruled with the aid of the dry stamp and proclamation from his new palace of Somerset House. Indeed, as W R Jordan and recently John Guy have commented, Somerset was a 'quasi- king'. Penry Williams in his recent book sums it up best when he states, until the Protector's fall in October 1549, Edward was a cypher in politics, exercising little influence of his own'.

The pivot of power

However, he continues, 'He was like the king on a chessboard, having small room for manoeuvre, but crucial to the development of the game. Control of his person determined the possession of power'. It was to ensure physical possession of the king that Somerset had had his own brother executed on thirty-three counts of high treason and it was thus to reassure the people that Edward was shown to the citizens of London during the rebellions of 1549 and after the fall of Somerset in October of that year. Moreover, in the panic which seized Somerset as he realised all had turned against him, he left his hunting in Hampshire and rode like the wind to

Hampton Court where the king was in residence. He immediately issued a proclamation ordering a general muster to defend King and Protector, before retreating with the boy to the defences of Windsor. But, crucially, even at this tender age, Edward could have saved his uncle had he made it clear that Somerset was his choice of Regent. However, as David Starkey makes clear, the king signalled his regal distance from Seymour for all to see. He fell conspicuously ill with a convenient chill and complained bitterly of his cold, shabby surroundings, writing 'Me- thinks I am a prisoner here. Here be no galleries, nor no gardens to walk in.

Somerset was doomed when it was thus clear that the King had no time for him, as the Journal makes manifest. Edward comments, as Somerset's time ran out, 'the Council, about nineteen of them, were gathered in London, thinking to meet with the Lord Protector and make him amend some of his disorders'. It was Edward who declared that Somerset had treasonously threatened that 'if he were overthrown, he would run through London and cry "Liberty! Liberty!" to raise the apprentices' (19 October 1551). Somerset denied it, but no one would gainsay the king. Not once does he refer to Somerset as even his uncle and, whilst being fascinated with the detail of the trial of late 1551, the entry execution on 21 January 1552 is as cold and dismissive as it was possible to be 'the Duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o'clock in the morning'. Nothing more. The boy was clearly the son of Henry VIII.

Active Monarch

The man who was to become the Duke of Northumberland never made the mistake of his predecessor. His elevation to the Presidency of the Council and appointment as Great Master of the King's Household in February 1550 marked a complete change in the life and role of

Edward VI. Northumberland never forgot that he was merely a councillor, however grand, with no blood relationship with his King. Although he made physical possession of the King his first act in toppling Somerset, he treated him very differently. Edward was now nearly thirteen and needed to be acknowledged, and, if Northumberland was to remain his trusted and key councillor when Edward came of age, he had to work with him. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that Edward's own writings become much more detailed and show a greater grasp of the minutiae of government from this time. That is not to say that Northumberland did not manipulate where he could. He clearly exploited Cranmer's influence with his Protestant protègè in order both to secure the addition of his own adherents to Edward's Privy Chamber in the persons of men such his own son-in-law, Sir Henry Sidney, his brother, Sir Andrew Dudley, and others such as Sir Thomas Darcy, and also to nullify the influence of Wriothesley, Arundel and

any who threatened his position. The Privy Council was also packed with his supporters, such as the Duke of Suffolk, Sir John Gates and Sir William Cecil, many of whom served also in the

Privy Chamber. But, one should not assume, therefore, that Edward was thus shut out. One could argue that Northumberland simply imposed his men upon the king; but Edward would clearly now have none of the 'catholic sort' about him. He had previously commented that he was not surprised that Bishop Thirlby had voted against the first Prayer Book, as a bishop who had spent so long with the emperor was bound to 'smell of the interim'. All of his servants shared two characteristics - his religion and his favour.

In August 1551, aged almost fourteen, Edward began to attend meetings of the Council on a regular basis, as well as being educated by Sir William Cecil, Sir William Petre and others in the business of state-craft. As Court and Council now so overlapped, the servants in his Privy

Chamber with whom he discussed the affairs of the day were also the very officials who debated in the Council and suggested policy in the conciliar form of government which

Northumberland advocated in contrast to his predecessor. Indeed, Jehan Scheyfve, the Imperial

Ambassador, commented in 1552 that 'Northumberland... is beginning to grant him [Edward] a great deal of freedom'. Edward kept a full, open table at Greenwich over the Christmas of 1551 and made a successful progress with a punishing schedule through the South in the summer of

1552. Williams comments that 'it was a sign both of restored order in the provinces and of

Edward's emergence as an active monarch'.

Personal power

In fact, Edward could not wait to exercise his prerogative powers. In the spring of 1552 the

Council under Northumberland's Presidency agreed that the king should attain his full majority and assume complete responsibility for the government of his kingdom in October 1553 when he became sixteen, two years earlier than might have been expected. Thus, are we to deduce that when he died less than four months before this majority, he was merely a puppet of his elders and of no real relevance to affairs of state? This idea does not make sense and the evidence does not support it. One should turn at this juncture to the political papers which the boy composed. There is not room here to discuss them in detail, but they clearly show a King who was appraised of the issues of the day, interested in the minutiae of administration and demanding response from his Council - as shown in the 'Memorandum as to Ways and Means'

(Summer 1552) and 'Certain Articles Devised and Delivered by the King's Majesty for the

Quicker, Better, and More Orderly Dispatch of Causes by His Majesty's Privy Council' (15

January 1553). His 'Memorandum for the Council' (13 October 1552) considers the financial problems of the government and broadens out into a searching set of proposals. Twelve members of the Council (an unusually full attendance, including Northumberland, Suffolk,

Winchester and Cecil) were present to discuss them. This was more than lip service to a puppet king.

If doubters as to this theory of involvement demand actions, then they can have them. In March

1551, Mary entered London at the head of a large retinue of knights and gentleman.

Apologising to her brother that she had not come before owing to ill-health, Edward replied that

God had sent her illness whilst granting him health and then proceeded to demand that she give up her Catholicism, even in private. Her Household officers were to be arrested if they permitted private masses, despite any assurances which Somerset was supposed to have made in the past. All the evidence demonstrates that Edward was the driving force behind his sister's persecution. It was only after Charles V threatened war if Mary was made to conform that he relented, as his Journal makes clear. But in finance also, Edward would not tolerate opposition, even as early as October 1551. Lord Richard Rich, the Lord Chancellor finally got his comeuppance when he refused to forward a royal commission because it had not been signed by enough councillors. As his Journal of 1 and 2 October demonstrates, Edward was outraged and

wrote to him stating that this would put him 'in bondage'. Rich gave in, fell ill and soon gave up office. John Murphy observes that the letter in question was one which the king 'had willed any

[one] about me to write'; it had been produced by Edward's private secretariat in his Privy

Chamber. As Murphy continues, 'This showed very clearly which way the wind was blowing… it was Northumberland's great skill to trim his sails to the wind. With the King he was everything; without him, he was nothing'. Rich had found this out to his cost, as had Somerset before him.

The succession - whose plot?

The exclusion of Mary and Elizabeth from the throne and the setting up of Jane Grey to rule after Edward's death have been much debated. Whilst this would have made Northumberland the father-in-law of the Queen Regnant, Edward's 'Device' was not a plot hatched by John

Dudley for his benefit. It originated with Edward to ensure a Protestant successor. It was only when he became really ill in the last two months that it was realised that Edward's insertions in the succession, the various 'heires masles' of the women named, had not been born - and there was no impending prospect that any would be! It was only then that Jane herself was made the heir. Undoubtedly, Northumberland would benefit, but when Jane had married his son, she was not the heir to the throne and it was expected that Edward would live long. Northumberland, like all his contemporaries, was merely making another wise marriage, in this case by connecting himself through his fourth son to the daughter of his chief ally, the Duke of Suffolk. It was only later that this excellent marriage alliance was to give Northumberland's son a crown, however briefly. The judges summoned to draw up a formal will at first refused, pleading the existing statutes of 1544, but at Edward's insistence they gave way, letters patent were issued and the

Councillors swore to observe Edward's settlement. The minor may have been challenged but, whilst he lived, his word was law

This article cannot hope in so short a space, and with incomplete evidence available in such a short reign, to prove that Edward ruled. Of course, he did not. However, it does seem that a closer examination of the evidence than is usually undertaken at A-Level suggests that Edward was anything but irrelevant and that from 1550, and as he grew older, he took an increasingly significant and individual role in the work of his Council acting in his royal name.

Who was Who?

Sir William Cecil,

Thomas Cranmer,

John Dudley,

Lord Thomas Darcy,

Sir Andrew Dudley,

Secretary of State (1550 1553)

Archbishop of Canterbury

Vice Chamberlain and Captain of the Guard (1550)

Lord Chamberlain (1551-1553)

Northumberland's brother and one of the Principal

Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber (1550-1553)

Viscount Lisle (1542), Earl of Warwick (1547), Great

Master and Lord President (1550), Duke of

Northumberland (1552)

Henry FitzAlan,

Sir John Gates,

Henry Grey,

William Parr,

Hugh Latimer,

William Paulet,

Sir William Petre,

Lord Richard Rich,

Edward Seymour,

Thomas Seymour,

Sir Henry Sidney,

Sir Michael

Earl of Arundel, Lord Chamberlain (1546-1550), fell foul of Northumberland

Vice-Chamberlain, Captain of the Guard, keeper of

Edward VI's dry stamp (1551-1553)

Marquis of Dorset (1547), Duke of Suffolk (1551), father of Lady Jane Grey

Earl of Essex, Marquis of Northampton, Great

Chamberlain (1550-1553) former Bishop of Worcester

Lord St John, Earl of Wiltshire, Marquis of

Winchester, Lord Treasurer (1550 - 1553)

Principal Secretary (1544-1553)

Lord Chancellor (1547-1551) brother of Jane Seymour and uncle of Edward VI,

Earl of Hertford (1541), Lord Protector (1547), Duke of Somerset (1547)

Younger brother of Somerset, Lord Seymour of

Sudeley and Lord High Admiral (1547), secretly married Catherine Parr (1547), suitor of Princess

Elizabeth (1548)

Northumberland's son-in- law, close friend of Edward

VI, Gentleman of the Privy Chamber (1550 - 1553)

Somerset's brother- in-law, First Gentleman of the

Privy Chamber, keeper of Edward