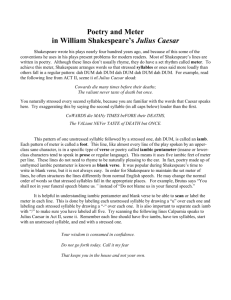

Scansion Handout

advertisement

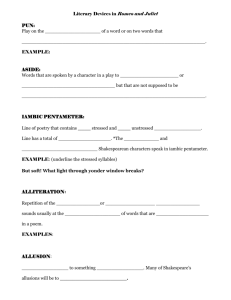

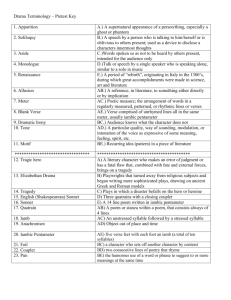

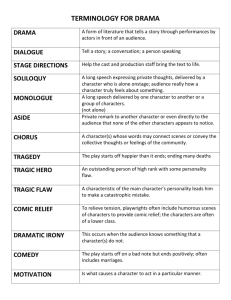

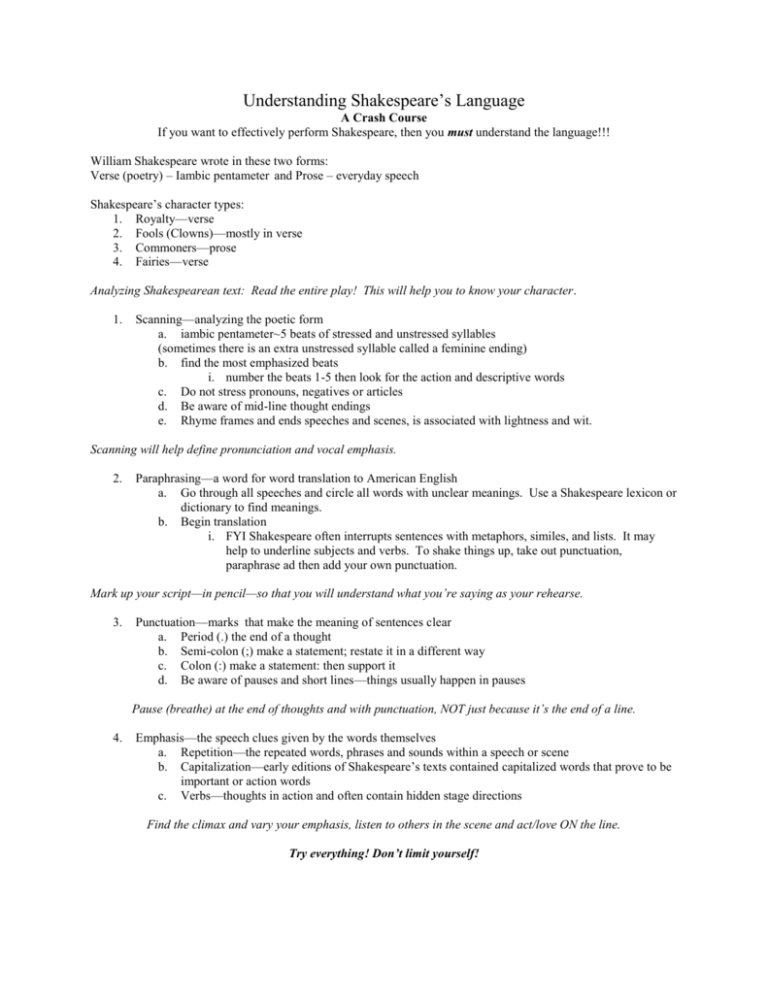

Understanding Shakespeare’s Language A Crash Course If you want to effectively perform Shakespeare, then you must understand the language!!! William Shakespeare wrote in these two forms: Verse (poetry) – Iambic pentameter and Prose – everyday speech Shakespeare’s character types: 1. Royalty—verse 2. Fools (Clowns)—mostly in verse 3. Commoners—prose 4. Fairies—verse Analyzing Shakespearean text: Read the entire play! This will help you to know your character. 1. Scanning—analyzing the poetic form a. iambic pentameter~5 beats of stressed and unstressed syllables (sometimes there is an extra unstressed syllable called a feminine ending) b. find the most emphasized beats i. number the beats 1-5 then look for the action and descriptive words c. Do not stress pronouns, negatives or articles d. Be aware of mid-line thought endings e. Rhyme frames and ends speeches and scenes, is associated with lightness and wit. Scanning will help define pronunciation and vocal emphasis. 2. Paraphrasing—a word for word translation to American English a. Go through all speeches and circle all words with unclear meanings. Use a Shakespeare lexicon or dictionary to find meanings. b. Begin translation i. FYI Shakespeare often interrupts sentences with metaphors, similes, and lists. It may help to underline subjects and verbs. To shake things up, take out punctuation, paraphrase ad then add your own punctuation. Mark up your script—in pencil—so that you will understand what you’re saying as your rehearse. 3. Punctuation—marks that make the meaning of sentences clear a. Period (.) the end of a thought b. Semi-colon (;) make a statement; restate it in a different way c. Colon (:) make a statement: then support it d. Be aware of pauses and short lines—things usually happen in pauses Pause (breathe) at the end of thoughts and with punctuation, NOT just because it’s the end of a line. 4. Emphasis—the speech clues given by the words themselves a. Repetition—the repeated words, phrases and sounds within a speech or scene b. Capitalization—early editions of Shakespeare’s texts contained capitalized words that prove to be important or action words c. Verbs—thoughts in action and often contain hidden stage directions Find the climax and vary your emphasis, listen to others in the scene and act/love ON the line. Try everything! Don’t limit yourself! Shakespearean Language Terms You Should Know Scansion: the art of indicating stresses in a poem—more than just pointing out the syllables, but listening to how the poem should sound and therefore gathering meaning Foot: the basic “molecule” of poetry, usually consisting or two or three syllables Iamb: a foot containing one unstressed syllable, followed by one stresses syllable Meter: when stresses occur at fixed intervals in a line of poetry or blank verse, it is said to have meter Pentameter: a line containing five poetic feet Iambic Pentameter: you can figure it out, I think (or if you don’t feel like thinking, it’s a line of poetry with five iambs per line) Blank Verse: Unrhymed iambic pentameter Shared verse line: the five feet of one line are shared by more than one character Elision: eliminating or “mushing” words or syllables together to preserve the meter Verse: another term for poetry Prose: everyday, un-metered speech Assonance: Repeated vowel sounds Consonance: Repeated consonant sounds Masculine Endings: a ten beat line that ends on a strong syllable Feminine Endings: an eleven beat line that, therefore, ends on a weak syllable Alexandrine Lines: a twelve count line that, therefore, ends with a strong syllable Half Lines: an incomplete line, often left that way for emphasis or to allow action Couplets: the last two rhymed lines ending a speech Hamlet II ii Oh what a rogue and peasant slave am I! Is it not monstrous that this player here, But in fiction, in a dream of passion, Could force his soul so to his own conceit That from her working all his visage wann’d. Tears in his eyes, distraction in’s aspect,\ A broken voice, and his whole function suiting With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing!