Poetry and Meter in William Shakespeare*s Macbeth

advertisement

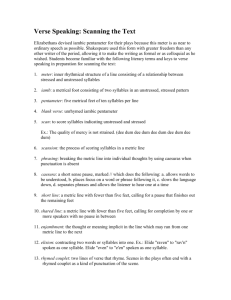

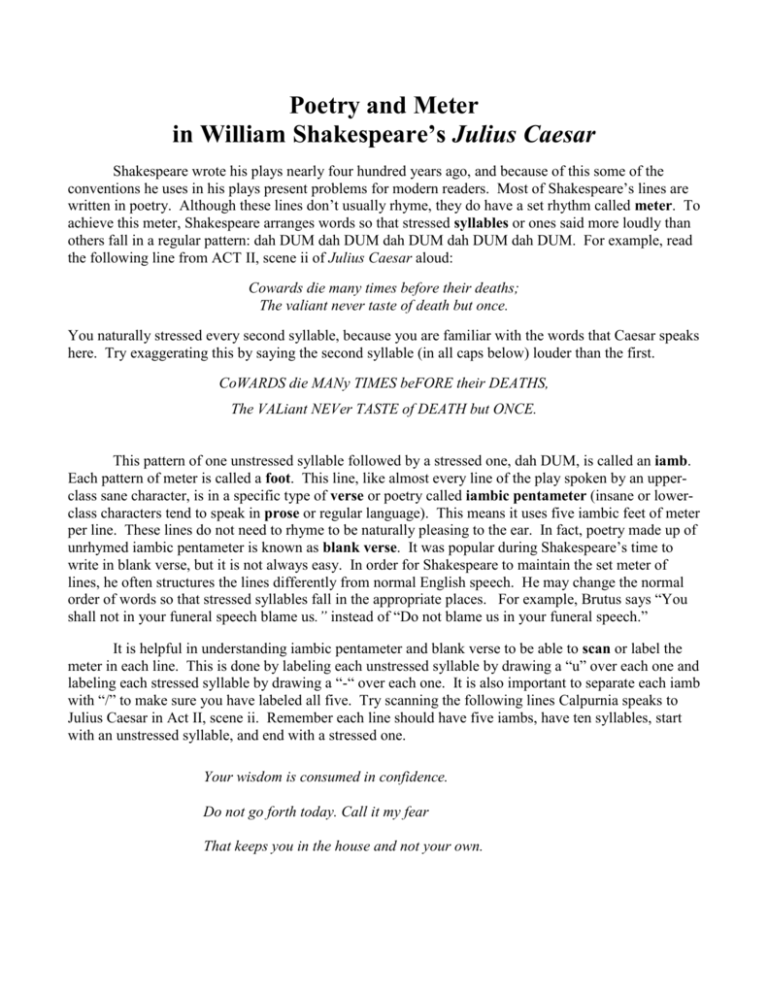

Poetry and Meter in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar Shakespeare wrote his plays nearly four hundred years ago, and because of this some of the conventions he uses in his plays present problems for modern readers. Most of Shakespeare’s lines are written in poetry. Although these lines don’t usually rhyme, they do have a set rhythm called meter. To achieve this meter, Shakespeare arranges words so that stressed syllables or ones said more loudly than others fall in a regular pattern: dah DUM dah DUM dah DUM dah DUM dah DUM. For example, read the following line from ACT II, scene ii of Julius Caesar aloud: Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once. You naturally stressed every second syllable, because you are familiar with the words that Caesar speaks here. Try exaggerating this by saying the second syllable (in all caps below) louder than the first. CoWARDS die MANy TIMES beFORE their DEATHS, The VALiant NEVer TASTE of DEATH but ONCE. This pattern of one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one, dah DUM, is called an iamb. Each pattern of meter is called a foot. This line, like almost every line of the play spoken by an upperclass sane character, is in a specific type of verse or poetry called iambic pentameter (insane or lowerclass characters tend to speak in prose or regular language). This means it uses five iambic feet of meter per line. These lines do not need to rhyme to be naturally pleasing to the ear. In fact, poetry made up of unrhymed iambic pentameter is known as blank verse. It was popular during Shakespeare’s time to write in blank verse, but it is not always easy. In order for Shakespeare to maintain the set meter of lines, he often structures the lines differently from normal English speech. He may change the normal order of words so that stressed syllables fall in the appropriate places. For example, Brutus says “You shall not in your funeral speech blame us.” instead of “Do not blame us in your funeral speech.” It is helpful in understanding iambic pentameter and blank verse to be able to scan or label the meter in each line. This is done by labeling each unstressed syllable by drawing a “u” over each one and labeling each stressed syllable by drawing a “-“ over each one. It is also important to separate each iamb with “/” to make sure you have labeled all five. Try scanning the following lines Calpurnia speaks to Julius Caesar in Act II, scene ii. Remember each line should have five iambs, have ten syllables, start with an unstressed syllable, and end with a stressed one. Your wisdom is consumed in confidence. Do not go forth today. Call it my fear That keeps you in the house and not your own. Sometimes, however, Shakespeare rhymes lines in iambic pentameter. These rhyming couplets are usually found at the end of scenes, acts, and entire plays. They let the audience know the moment is over. Sometimes Shakespeare also uses these couplets to give importance to a magic speaker or a moment of foreshadowing. Try scanning this rhyming couplet Brutus speaks at the end of Act V, scene iii, ‘Tis three a clock; and Romans, yet ere night We shall try fortune in a second fight. Julius Caesar, like all of Shakespeare’s plays, is full of these wonderful passages in blank verse and rhyming couplets. Below is a list of the major terms addressed in these pages. These are not the only poetic elements this play posses, but they are a good place to start. Take some time now to look back at the information on this sheet define these terms below, and look for examples of them as you read later. (Hint- Some of these terms are defined on this sheet, but you may need your textbook to look up others. The important thing is to make sure you understand them all) prose verse drama verse drama syllables meter foot iamb iambic pentameter blank verse rhyming couplet scan