File

advertisement

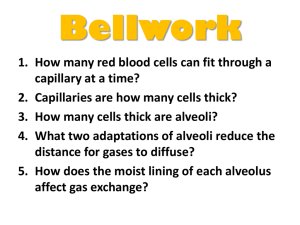

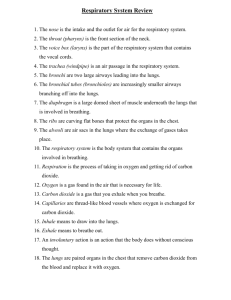

Lesson 4- The Respiratory System and the Renal System Assignment: • Read Chapters 5 and 6 in the textbook. • Read and study the lesson discussion. • Complete Lesson 4 Worksheet Objectives: After you have completed this lesson, you will be able to: • Identify the basic components of the respiratory tract. • List and discuss the function and control of breathing. • Identify and name the basic structures in the renal systems. • Explain the functions of the renal system. • Identify structures within the kidney and detail the formation of urine and its regulation. • Evaluate urine and blood as a measure of the health of the animal and the urinary system. • Discuss the clinical significance of the academic material in this lesson. • Identify common disorders of the respiratory and renal systems. The Respiratory System One fundamental concept that you need to remember as you are working through these lessons is that all animals, including humans, contain about 99% of the same genetic material. It is the remaining 1% that distinguishes humans from dogs, and birds from alligators. This is why most of the discussions regarding systems of the body can be related to all animals, including humans. In other words, anatomy, physiology, function, and disorders of these systems, for the most part, are very comparable in all species. According to information obtained from ThinkQuest.org, All animals need food, water, and air to survive. The respiratory system of each animal is what meets these needs. Oxygen is taken from outside and exchanged with carbon dioxide in the lungs. That exchange is called respiration and is composed of four basic events: • pulmonary ventilation—Air inside the lungs is exchanged with fresh air from the outside. • external respiration—Fresh air in the lungs is moved into the blood, and used air in the blood is moved into the lungs to be removed. • respiratory gas transport—The circulatory system pumps the blood into which the fresh air has been moved throughout the body. • internal respiration—The cells of the body remove air from the red blood cells and move the carbon dioxide into them. External Respiration The subsystem that removes carbon dioxide from the lungs and moves in fresh air from outside is made up of the nasal cavity (nose), the pharynx, the larynx, the trachea, the bronchi (and all the smaller branches of the bronchi), and the air sacs, or alveoli, to which the entire external respiration subsystem leads. The respiration zone consists of the bronchioles (not the large bronchi), the alveolar ducts, and the alveoli, all of which basically make up the lungs. This is where the oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged. All other organs in the external respiration subsystem make up the conducting zone. During the trip that air takes through the conducting zone, it is humidified, cleaned, and warmed so that it does not harm any of the delicate organs that it passes through. When the air finally reaches the alveoli, it is closer to the air in the tropics, which is the kind of air the lungs prefer. The nose is the first and last organ that air passes through. The nose serves some very important functions. As part of the conducting zone, it cleans the air of dust and other impurities, warms the air if it is too cool, and moistens the air if it is too dry. Though not related to respiration, the nose also helps humans speak and is the organ that gives you the power to smell. After passing through the external nares (nostrils), air passes through the nasal cavities. The nasal septum separates the two nasal cavities. Immediately after passing through the nostrils into the nasal cavities, the air begins to be purified, humidified, and warmed. The skin of the vestibule, the part of the nasal cavities behind the nostrils, has sebaceous and sweat glands and hair follicles, which catch the dirt and other impurities that may be in the air. The hair growing out of the follicles are called vibrissae. The olfactory mucosa is what detects scents that are inhaled. The serous glands excrete enough lysozyme, an enzyme that destroys bacteria, to keep the air breathed mostly pure, which is about a quart a day. The pharynx, most commonly known as the throat, serves dual purposes. Not only does it move the air into the lungs, but it also moves food into the stomach. [The length of the pharynx varies and depends upon the animal. The pharynx is separated into three different regions. Location and function determine these separations.] The nasopharynx is located above the part of the pharynx that food enters. At the base of the nasopharynx are the soft palate and its pendulous uvula. When swallowing, there is a possibility that food will enter into the nasopharynx and nose. This would severely disrupt breathing. So when an animal swallows, the soft palate and its pendulous uvula point upwards, blocking off the nasopharynx so that neither air nor food can pass through it … . The middle ear is also connected to the wall of the nasopharynx so that ear pressure can be equalized. Infections in the nasopharynx are commonly followed by ear infections because of this. The mouth leads to the oropharynx. The mucous lining the walls of the oropharynx change slightly to adapt for handling food as well as air. It is here that the two tonsils are located. One is at the entrance from the mouth into the oropharynx and the other is somewhat deeper. The laryngopharynx also serves as a common passageway for both food and air. At the base of the laryngopharynx is the esophagus, which directs food and air to where they should be. Sometimes it can get confused and make mistakes. Swallowing air can lead to burping more often. Inhaling food or liquid causes an animal to cough until it is expelled. The larynx, also known as the voice box, is what allows animals to "speak." The larynx has an inlet at the top that allows substances to pass through it or not. When food is being swallowed, the inlet is closed, forcing food into the stomach. When air is being breathed, the inlet is wide open so that air can enter the lungs. The trachea, or windpipe, connects the larynx to the bronchi. This organ differs from others in the neck in that it is flexible, stretching to four or five inches long and about one inch in diameter. The trachea is lined with mucous called the mucociliary escalator, which represents the mucous and cilia and carry the foreign substances up to be swallowed. The trachea is made up of between sixteen and twenty cartilage rings in the shape of a "C." Because the trachea is so flexible and twistable, without these cartilage rings, it would collapse under the partial vacuum formed when inhaling. The open part of the "C" shape is covered with the trachealis muscle, which can stretch itself to prevent tracheal tearing when swallowing large things. When an animal coughs, the muscle also contracts to force air out at a faster speed to dislodge food or other stuck foreign objects. The trachea branches off into two main bronchi, the left and right primary bronchi, which lead to the left and right lung, respectively. The right lung is slightly wider, shorter, and taller than the left, which makes it more vulnerable to foreign invasion. At this point in breathing, the air has been moistened, purified, and warmed. The first few levels of bronchi are supported by rings of cartilage. Branches after that are supported by irregularly shaped discs of cartilage, while the latest levels have no support whatsoever. Respiration begins when the terminal bronchioles lead into the respiratory bronchioles. These bronchioles are covered with thin-skinned air sacs that allow for gasses to pass through them. These sacs, which contain alveoli, are called alveolar sacs, and are at the end of the alveolar ducts. The alveoli are very small curves in the sac walls. The lung has millions of alveoli, which give the lungs an incredible surface area for gas exchange. Though fairly impossible to measure exactly, the surface area is approximated at 70-80 square meters or a square between eight and nine meters on each side. The alveoli are covered in interlinking capillaries through which blood flows. The alveoli and the capillary walls form the respiratory membrane. The lungs rely simply on diffusion to exchange the gasses, and that moves enough gas to have a steady supply of oxygen in the body. The respiratory membrane is [very thin,] so diffusion happens pretty efficiently. For maximum efficiency, the amount of blood passing through a capillary on an alveoli and the amount of gas exchange should match precisely. When there is not enough gas in the alveoli, certain pulmonary vessels tighten, slowing the flow of blood, which causes more blood to flow elsewhere. When there is a lot of gas exchange happening, those vessels widen, allowing more blood to pass through. A similar process happens to bronchioles. When an alveoli has a lot of carbon dioxide in it, the bronchioles that connect it to the outside air widen, allowing it to leave more quickly. With the lungs coming in direct contact with the air, you would think that it could supply its own blood supply. This isn’t so. The bronchial arteries, which branch from the aorta, supply the lungs with oxygen, and the bronchial and pulmonary veins take old blood away. The pleurae is a thin, double-layered tissue which lines the walls of the lungs and heart. Due to the fact that it produces pleural fluid, the pleurae helps the lungs to glide easily against the rib-lining tissues, the thoracic wall, when the lungs take in air. Also, the pleurae is essential to breathing because it serves as potential space. This important function helps the lungs form a vacuum which sucks in air from the atmosphere. In addition, its capability to stretch and divide the lungs into two compartments, a lower and an upper lung, allows other organs to move without interfering with respiration. As mentioned before, respiration is the result of a vacuum formed inside the lungs. The lungs themselves don't have muscles, so they can't force themselves to expand. Instead of each alveoli or bronchiole having a muscle, there is one big muscle called the diaphragm. The diaphragm lines the lower part of the chest cavity, sealing it off air-tight from the rest of the body. When the animal inhales, the domeshaped diaphragm contracts, straightening itself out. This lowers the pressure in the chest cavity, causing air outside the lungs to rush in to fill the space. Though air can expand, … the low pressure inside pulls in air to equalize the pressure. The lungs, connected at the ends by cartilage, expand, stretching the cartilage to allow room for the lungs to hold air. With the ribs expanding outward only a few millimeters, and the diaphragm lowering only a few millimeters, the volume of the chest cavity increases by about half a liter, which is the average inhaling amount. The exact opposite is the cause for expiration. When the diaphragm relaxes, moving upwards, the chest cavity [decreases] in volume, raising air pressure in the lungs and forcing air out into the atmosphere. Muscles, such as the diaphragm, cannot push out, but only contract. When an animal inhales, different tissues in the chest cavity stretch. Relaxing the diaphragm allows them to return to normal size, which raises the pressure, thus forcing the air out … . If an animal needs to exhale quickly, such as in coughing or sneezing, the abdominal walls can contract, doing the same things that the stretched tissues do. Elasticity is incredibly important. Animals who suffer from asthma type conditions do so because their lungs have lost most of their original elasticity. As a result, they must actively breathe out; it doesn't happen automatically anymore. This condition requires animals to expend extra energy just to stay alive. Internal respiration is the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen in the cells of the body. It happens in much the same way as gas exchange in the lungs through diffusion. Red blood cells carry the oxygen to the body and bring back the carbon dioxide to the lungs. Watch this video which explains what respiration is and why living things need to breathe. The respiratory system is susceptible to a number of diseases, and the lungs are prone to a wide range of disorders caused by pollutants in the air. The most common problems of the respiratory system are asthma, bronchiolitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, and pulmonary hypertension. Each one of these disorders attacks some part of the respiratory system and is very comparable to the conditions in humans. Being able to identify respiratory structures and their associated functions, from the nose to the lungs, allows veterinarians to diagnose and treat such disease conditions as pneumonia and roaring. Moreover, the respiratory rate provides a key piece of information to practitioners when accessing the overall health of animals. The status of the respiratory system affects the breathing, and therefore the total health, of animals. The Renal System The renal system is also known as the urinary system or the excretory system. This system can be subdivided into two major functional subdivisions: the first is the kidney, where the manufacturing of urine takes place. We will consider in this lesson the structure of the functional unit of the kidney, the nephron, in detail. The second subdivision of the system is the excretory passage, which consists of all of the structures for collecting urine and draining it out of the body, including the ureter, the bladder, and the urethra. We will consider each of these separately a bit later. According to Dr. Thomas Caceci, a professor from the Virginia—Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, "The kidney did not evolve primarily as an excretory organ. Though we think of it as one, and though in mammals that is one of its important functions, the primary purpose of the kidney is to control the flux of ions out of the body, and to conserve water." In other words, the kidney is responsible for controlling what is included in waste materials. If you split a kidney along its long axis, you will be able to differentiate between the cortex and the medulla. The cortex is the outer region. This is where the first parts of the urine-producing nephrons and parts of some tubules are located. The medulla is the deeper region and is composed entirely of tubules (Caceci). Dr. Caceci continues, "The kidney is a place in which blood is filtered. The blood flow is the driving force behind urine formation, so it is important to consider vascular relationships before we look at the process of urine formation in detail. Blood enters the kidney via the renal artery, and is distributed through a series of smaller vessels." After entering the kidney, each renal artery breaks up into subdivisions. In these subdivisions is a network of arteries which directly supplies blood to the capillaries in the renal system. It is the capillaries that clean the waste from the blood. Eventually, drainage from all of the capillaries is collected into larger and larger veins until it leaves the kidney through the renal vein. According to Dr. Caceci, The nephron [is] the basic unit of the kidney. Urine production is essentially a process of filtration followed by modification of the filtrate. Urine starts as an ultrafiltrate of blood, from which all of the formed elements and most of the larger soluble elements (e.g., proteins) have been removed. Blood is brought to the renal corpuscle via the route described above. Propelled by the pressure of continuing filtration, the urine is driven through the rest of the nephron, and the various parts of it modify the product until it’s released and drains out through the excretory passages. The exact concentration and composition of the urine varies, depending on what needs to be cleared and how much water is available to do the job. There are many complicated inner-anatomical parts to the nephron, but, for the purpose of this course, it is important to remember that each nephron is a continuous tubular unit. It empties through its collecting tubule into a larger collecting duct. This duct receives input from many nephrons. It could be compared to several garden hoses emptying into the same tank. Up to a million nephron can be found in a typical mammalian kidney (Caceci). The rest of this first phase consists of a complicated mixture of anatomical and chemical processes that basically filters and prepares urine so that it can be removed from the body. Since the body has produced urine, it is now necessary to get rid of it. The urine sets in the collecting system (ducts) and flows through a series of tubes to the outside. The renal pelvis is the upper end of the ureter, attached just below the tips of the kidney's lobes. It catches the urine and drains out. The ureter is simply a muscular tube that connects the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The urinary bladder is a temporary storage organ for urine; its capacity is measured in milliliters …. The wall of the bladder is similar to that of the ureter, but there are said to be three layers of smooth muscle …. There is also a fair amount of elastic connective tissue in the wall to provide for elasticity and dispensability (Caceci). The urethra is the final passageway of the excretory system. It is the tube that releases urine from the vulva (or penis) out of the body. The general health of any animal depends on how well the urinary system functions. Waste products build up in the body when this system fails to function. Serious disorders and even death from toxicity in the body can result. The following are common urinary system disorders: • Nephritis is an inflammation of the nephron in the kidney. This condition can be caused by almost anything that irritates the kidneys. Most of the time, this condition is not fatal, and no damage to other kidney parts is expected. • Pyelonephritis refers to the inflammation of the renal pelvis and connective tissue of the kidney. Bacterial infection or urinary blockage is usually the cause of this condition; however, it can also be caused by viruses. • Cystitis is an inflammation of the bladder and most often occurs because of an infection caused by bacteria that enter the bladder through the urethra. • Urethritis is an inflammation of the urethra that results most of the time from a bacterial infection. Most of these inflammatory diseases of the urinary system lead to difficult or painful urinating. • Bladder or kidney stones form from the salts of calcium and uric acid. These stones form by precipitation around some sort of bacteria, blood clumps, or similar foreign substances. Diet can also predispose bladder or kidney stones. • Blood in the urine is a symptom and not a disease. This could mean that there is the presence of a serious disease in another part of the renal system. Urine can also be an indicator of cancer in the kidney or bladder. It is very important that the kidneys be kept in normal functioning condition with sufficient water consumption. Insufficient water increases the specific gravity of the excretion, thus increasing the work of the excretory system. This leads to irritation and inflammation. Try this drag and drop quiz about the parts of a kidney. Try some target practice to review the components of the kidney and nephron. Summary Veterinarians depend on their extensive knowledge of the renal system to treat common illnesses in animals including dehydration and bladder infections, but this same knowledge is also used to detect other, more serious health issues like potential kidney failure. Specialized knowledge of urine is also helpful to anyone in this field of medicine. Sources Cited: Caceci, Dr. Thomas. "Urinary System." Veterinary Histology. 1998. 28 Dec. 2006 <http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/Curriculum/VM8304/lab_companion/Histo-Path/VM8054/Labs/La Oracle Education Foundation. "The Respiratory System." ThinkQuest. 1996. 28 Dec. 2006. <http://library.thinkquest.org/2935/Natures_Best/Nat_Best_Low_Level/Respiratory_page.L.html>.