TP_ChrisWhittaker

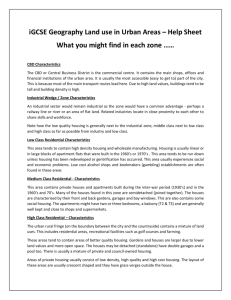

advertisement

Christopher Whittaker 1 Job Decentralization and Residential Location: A Concise Technical Presentation of the Work by Leah Platt Boustan and Robert A. Margo Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Urban economists often ask a similar question in relation to the origins of cities: which came first, the jobs or the workers? Leah P. Boustan and Robert A. Margo set out to provide some insight into this question. Specifically, they question how the spatial distribution of employment opportunities influences urban Americans' choice of residential location. The question and research is largely prompted by a trend of suburbanization in the United States over the past 50 years. Since 1960, the share of metropolitan Americans living in suburbs away from the central city has risen noticeably. Over the same period of time, the number of metropolitan residents working away from the city has similarly risen. Thus, urban economists question whether it was workers following jobs or jobs following workers that caused this decentralization of both employment and population. The pair's results suggest that the decentralization of employment appears to have been an important (though by no means complete) cause of residential location and suburbanization. From these results, they conclude that in order to attract residents to central cities, creating new jobs in the Central Business District (CBD) is more effective at the margin than simply creating jobs in the larger metropolitan area. Their work ultimately adds to the tools that urban economists have to analyze urban growth, building on such work as the monocentric city model. Presentation of the model Boustan and Margo seek to "estimate the impact of employment location on residential location" (3). Though an ideal experiment would randomly place the location of a given industry randomly throughout a city and look at where its workers choose to live, rarely are opportunities like this available on such a large or measurable scale. In reality, the variation between locating work and workers may be endogenous as workers seek to reduce commuting costs and businesses seek to provide compensation in the form of a decreased commute time. Since causality would be difficult to demonstrate, Boustan and Margo use a natural experiment to evaluate the impact of employment opportunities on residential location. The two choose to look at employment in state government in a capital city as a reasonable analogue. According to Boustan and Margo, employment in state government in a capital city has two important advantages that make it a reasonable choice. First, the location of state government long predates any form of suburbanization; originally most state capital cities formed prior to the 1900's Christopher Whittaker 2 and workers located adjacent to the CBD. Second, the majority of buildings in the capital that engage in state government still remain in the CBD (and likely will continue to do so). Therefore, state capital cities and their government buildings vary spatially based on historical reasons that are unrelated to current residential development patterns. Therefore, the model focuses solely on worker decisions and avoids "concerns about reverse causality" (3). However, due to the particular development of the cities, there are possible differences between state workers in capital and non-capital cities (for instance, level of education). To address this concern, Boustan and Margo compare state workers to both private and public-sector workers in their cities. In their words, "the key identifying assumption is that state workers in both city types [capital and non-capital] are otherwise identical but for their 'assignment' to the state capital" (5). However, as workers are engaged in different types of employment (see table 1, pg. 6), Boustan and Margo begin with a model to test whether observable characteristics of the state workforce vary between capital and non-capital workers. They estimate: Xijk = α + β1(state worker × capital city)ijk + α2(state worker)ijk + β3(capital city)ijk + εijk , (1) where that X is a vector of individual characteristics, including race, gender, age, and educational attainment and i, j, and k are used to index individuals, metropolitan areas and class of worker (i.e. state worker or not), respectively. The β1 coefficient is of particular important, as it reflects the interaction between being a state worker and living in a capital city. Boustan and Margo use a sample that includes more than 700,000 full-time workers in 127 metropolitan areas, 25 of which are state capitals (5). After running a regression analysis given this first equation (eq. 1), they find that "the main effects of being a state worker and living in the capital city are large and significant" (6). However, given several dimensions of personal characteristics, the only exception in which state workers in capital cities differ from state workers in other metropolitan areas is race. That is, state workers in capital cities are less likely to be black. They resolve this, stating that because African Americans are more likely to live in central cities, "if anything, the racial difference will work against our main findings" (6). Thus, the similarity of state workers in both capital and non-capital cities along observable dimensions (such as age, gender, education, race, marital status, etc.) supports their use of a difference-in-differences estimator, or the interaction of state work and capital city in the above vector equation (eq. 1). Christopher Whittaker 3 Boustan and Margo then demonstrate that state workers in capital cities are more likely to work downtown. This corresponds to the aforementioned benefit of state capital formation, where historical government buildings have long existed prior to current suburbanization trends. The regression that underlies this conclusion is the same as equation 1, but the dependent variable is replaced with a binary indicator variable for either working or living downtown (8). Now, "if workers based their residential location decisions on their job location we would expect that state workers in capital cities are also more likely to live downtown" (8). They proceed to show that this is true, that state workers in capital cities are 10 percent more likely to live downtown. The overall question is motivated by the relationship between employment and population locations. Boustan and Margo use the following estimating equation to look at this relationship: 1 if live in cityijk = α + β(=1 if work in city)ijk + θXijk + j + k + εijk. (2) Again, the difference-in-differences estimator can be used as a viable instrumental variable for working in the central city (9). The two present a fourth table, utilizing equation 2, that demonstrates the relationship between employment and residential location. I have included this particular table below because of its significance in the overall conclusion. They estimate the equation using both ordinary least squares (OLS) and the difference-indifferences estimator as an instrumental variable (IV) for working in the city center. They ultimately rely on the differences-in-differences estimator to reduce selection bias. They find that the relationship between working and living in the central city does not vary much between the OLS and instrumental variable treatment, but that "the effect of working in the CBD on residential location triples in size" (9). This is significant, because working in the CBD has a larger effect on housing location than simply working in the metropolitan area. The results from this table, using the instrumental variable, can be extrapolated to predict the overall effect on adding jobs to both the city and to the CBD. Since they note that 15 percent of jobs 4 Christopher Whittaker are typically located in the CBD, the following equation can be used to calculate the effect of adding 1,000 jobs to the city. (% jobs in CBD)(residents to CBD) + (% jobs in rest of city)(X) = Y residents in city (3) Applying the fact that 15 percent of jobs are typically located in the CBD to the coefficients under column 2 (IV) from table 4, we can calculate the impact of adding 1,000 jobs to the city. (0.15 jobs in CBD)(356 residents to CBD) + (0.85 jobs in rest of city)(X) = 246 residents in city (4) We find that X is equal to 227, providing a cumulative effect of adding jobs to the city of 246 new residents. This shows us that adding jobs to the CBD has a 57 percent greater effect on having residents locate in the central city than simply adding jobs to the city as a whole (=(356-227)/227). Boustan and Margo conclude by applying their results to the time variation in urban decentralization in the US between 1960 and 2000. As the percent of workers who worked in the city fell from 59.3 to 42.3 percent, using the instrumental variable estimate we can infer that "the share of workers who lived in the city would corresponding fall by 4.2 points (or 17% × 0.246; second column of table)" (10). Since the central city metropolitan population fell by 18.8 points over this same time period, we can infer that employment decentralization accounts for around 22 percent "of the observed suburbanization of population from 1960 to 2000" (10). Implications and extensions The model has several relevant implications for urban economics, policy development and methodological research. From the urban economic policy side, there are two primary implications. The first is a convenient "Rule of Thumb" for policymakers that want to understand the effects of urban population change with respect to the effects of proposed policies (18). In general, the model allows a policymaker to assume that one urban resident will be added or subtracted to the central city for every four jobs created or destroyed, respectively. This is a useful tool for back-of-the-envelope calculations, allowing policymakers to quickly analyze the impact of potential policy decisions. Second, the findings provide some pushback to the amenities-based theory for urban growth. While the creation of endogenous amenities (such as museums or art galleries) may lead to a revitalization of Christopher Whittaker 5 downtown urban areas, Boustan and Margo claim that unless job creation remains the central function of city centers, any amenities-based (or consumption-based) downtown revivals will fail to reach their full potential (18). Concerning methodological implications and extensions, Boustan and Margo believe that the historical record will continue to reveal opportunities for natural experiments in urban economics that have often been overlooked due to a prevailing notion that "locations are rarely determined by exogenous forces" (18). Ultimately, this study demonstrates the usefulness of understanding the relationship between job decentralization and metropolitan suburbanization trends. Further research could utilize this model with respect to global suburbanization trends, particularly in Europe and other developed nations. Original Paper Citation Boustan, Leah Platt, and Robert A. Margo. "Job decentralization and residential location." BrookingsWharton Papers on Urban Affairs Annual 2009: 1+. Academic OneFile. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.