Streetcar notes - Lakewood High School

advertisement

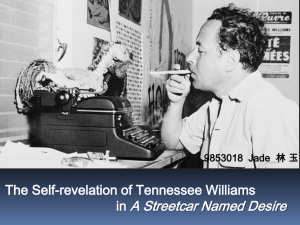

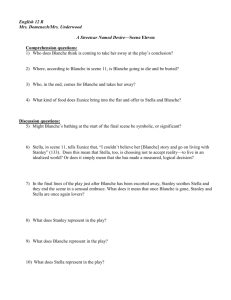

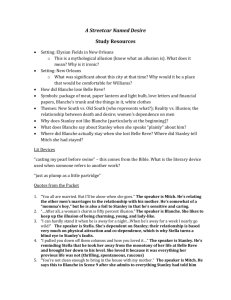

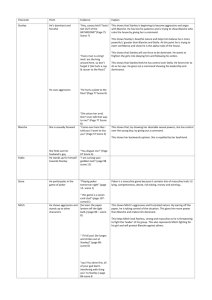

A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams “They told me to take a street-car named Desire, and then transfer to one called Cemeteries . . .” ~Blanche DuBois The Play Reveals the complexities of the individual and the relationships between characters. Requires examination to how characters react to words and actions. Focuses on “modern America,” post-WWWII. Won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1947. Adapted to a film in 1951, starring Marlon Brando as Stanley and Vivian Leigh as Blanche. The film version is differs in some places, as was required to get it produced. (More on that AFTER we read.) Tennessee Williams Born Thomas Lanier Williams on March 26, 1914 in Columbus, Mississippi, the son of Cornelius Coffin Williams and Edwina Dakin. Had an elder sister, Rose, who was eventually committed to a mental institution, and a younger brother Walter Dakin. Particularly close to mother (father worked away from home), a Southern belle and daughter of an Episcopal minister who enjoyed her status as a pillar of town society. 1918, the family moved to St. Louis, MO. Cornelius began to drink heavily. Edwina voiced her resentment at losing both her place in society and her close ties with her parents. As a reaction to his family life and being bullied by children in the neighborhood, Williams began to read books and write stories. Beginning in 1929, Williams studied at the University of Missouri at Columbia, at Washington University in St. Louis, and at the University of Iowa, while making a name for himself as a writer. 1944, debut performance of The Glass Menagerie. Williams moved to New Orleans (the setting for Streetcar). 1947, A Streetcar Named Desire produced in New York and Boston. 1955, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was a commercial success, but by this time Williams’ health was deteriorating and he abused alcohol and drugs. In fits of paranoia, he quarreled with his agent, Audrey Wood, and his lover, Frank Merlo. Over the next few decades, he wrote many unsuccessful plays and several of his earlier acclaimed plays (see above) were revived. Feb. 24, 1983, died during the night in the Elysee Hotel in NY after choking on a barbiturate. Historical Context The play takes place in the French Quarter of New Orleans shortly after World War II. The play explores the plight of impoverished Southern gentry. These families lost their importance when the South’s agricultural base was unable to compete with industrialization. The region’s agrarian economy, in decline since the Confederate defeat in the Civil War, suffered further after WW I. A labor shortage hindered Southern agriculture when male laborers were hired by the military or defensebased industries. Many landowners moved to urban areas to work. With increasing industrialization in the 1920s-1940s, the work force changed, incorporating large numbers of women, immigrants, and blacks. Women gained the right to vote in 1920 and the Southern agrarian family aristocracy ruled by men started to come to an end. After WWII ended, thousands of Americans struggled to determine their places after the war. Women returned from work to the household. Like their husbands, who had newly returned from war (many with depression and PTSD related issues), wives were having trouble acclimating to their old lives. Gender roles were changing, adding to the post-war stress and confusion. People were fighting hard to find a domestic status quo—as reflected in Streetcar. The play introduced American to prostitution, homosexuality, rape, domestic violence, alcoholism, and mental breakdowns/madness. Characters: Synopsis, Symbolism, and Imagery Blanche Dubois 30; from Laurel, Mississippi; widow (married at 16); English teacher She arrives, homeless (she has lost her teaching position and has been run out of the town where she resided), at her sister’s house at the beginning of the play. She wants desperately to leave her past (the Old South along with her sordid choices upon the loss of the family plantation) and begin anew, but is unable to. “Blanche” is French and means “white” or “fair.” DuBois is French and translates as “made of wood” (however, pronounced the American way it would be “do boys”—ironic given her “profession”). Blanche also chooses to wear white. The color white stands for purity, innocence, and virtue; her true nature is not like that at all. DuBois, “made of wood,” suggests something solid and strong, which is the exact opposite of her fragile nature and condition. Stanley Kowalski Stella’s husband and Blanche’s enemy. He dominates and assumes control over people. He wants no interference and, thus, does not like Blanche’s “interruption” of his life and his happiness. Stanley embodies the animal nature of man and is described with animal imagery. He is portrayed as an animal hunting his prey, as he seeks to destroy Blanche. Stella Kowalski Blanche’s sister; Stanley’s wife Stella means “star.” Stella is quite opposite the “star,” giving up her personality to become the woman Stanley wants her to be. Stella’s life revolves around Stanley and sex with Stanley. Stella is the connection between Blanche and Stanley because she contains character traits of both of them. Meaning and Naming: Place Names & Streetcar Names Belle Reve The DuBois family plantation in Laurel means “beautiful dream.” This emphasizes Blanche’s tendency to hang on to illusions. “Belle” is a feminine adjective to describe “Reve,” a masculine noun. This helps develop the theme of gender ambiguity (Blanche). Elysian Fields The name of the street where Stanley and Stella live. Allusion to Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid. Eylsium was part of the underworld and a place of reward for the virtuous dead. This was a temporary place on the souls’ journey back to life. Desire Streetcar that Blanche takes to the Kowalski house. Represents Blanche’s longing for love and companionship Cemeteries Streetcar that Blanche transfers to after Desire. Obvious symbol of death and Blanche’s descent into madness. Symbols throughout the play Games (poker and bowling—scene 3 and 11) Colors (look at Blanche and at the men’s clothing) Light (different characters’ response to light throughout the play) Chinese paper lantern (scene 3 and 9) Meat (Stanley and Stella) Bathing (Blanche) Music (the Varsouviana Polka and the “blue piano”) Bibliography Fischer, L. A Streetcar Named Desire Study Guide. Jericho Schools. N.d. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://www.jerichoschools.org/hs/teachers/lfischer/streetcar/streetcar.htm>. Small, Robert C. Jr. A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Edition of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. Eds. W. Geiger Ellis and Arthea J. S. Reed. NY: Penguin, 2004. Virgil. The Aeneid. Trans. John Dryden. 2001. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~joelja?aeneid.html>. Welsch, Camille-Yevette. “World War II, Sex, and Displacement in A Streetcar Named Desire.” Critical Insights. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press, 1971. Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire. New York: Penguin, 1974.