A Streetcar Named Desire_2011-2012

advertisement

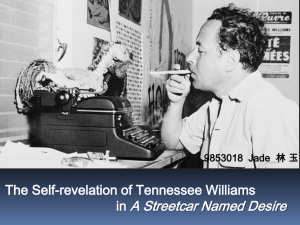

A Streetcar Named Desire – Tennessee Williams, 25 October, 2011 Biographical background [See Powerpoint for a photo of Williams] [See Powerpoint for a breakdown of the key events of Williams’ life] - - - Although he was born in 1911, Tennessee Williams did not exist until 1939, when he changed his name from plain Tom to Tennessee. Although there are various versions of how this renaming came about, one story suggests it was a nickname that Williams acquired when his friends couldn’t remember which Southern state he came from. They knew it had a long name, but in fact it was Mississippi, not Tennessee. Whether true or not, it does suggest that Williams was keen to stress his Southern identity, and as we’ll see, that Southernness was very clearly expressed in Streetcar. [For name stories, see Donald Spoto’s biography of Williams, The Kindness of Strangers, pp.66-67.] With his sister Rose, Williams grew up in various Southern towns, eventually settling in St. Louis, Missouri, where his father was branch manager of the International Shoe Company. During the 1920s, Williams wrote short stories, poems, articles, and travelled around Europe with his grandfather in 1928. Is persuaded to be a playwright by a production of Ibsen’s Ghosts that he sees in 1936. 1937: several plays produced by the Mummers amateur group in St. Louis. Studied playwriting and production at University of Iowa, 1937-1938. 1939: lives for a time in French Quarter of New Orleans. Perhaps has first significant homosexual relationship here. 1940: takes a playwriting seminar in New York with John Gassner, and has first lengthy homosexual affair in Provincetown. Rose is institutionalized in 1943 and is treated with lobotomy. 1944: The Glass Menagerie premiered in Chicago and transfers to a highly-successful Broadway run in 1945. Williams actually wrote a version of Streetcar during rehearsals for The Glass Menagerie in 1944, set it aside to write Summer and Smoke, and then came back to it when he was living in New Orleans in the autumn of 1945. He worked on it some more there and then re-wrote the play in one month whilst summering in Key West in 1946. Despite Williams’s misgivings (he was convinced that the play would be a failure, perhaps because of the great success of The Glass Menagerie), it ran on Broadway successfully for 855 performances, and became the first American play to win all three major awards: the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, and the Donaldson Award. New Orleans, immigration Williams came to live in New Orleans first on December 26, 1938, making a break from his family in an attempt to define his life and his work more sharply. As critics have noted, it was here that he changed his name from Tom Williams to Tennessee Williams. In the stage directions to the play, Williams describes the area around Stella and Stanley’s building as ‘poor but unlike corresponding sections in other American cities, it has a raffish charm. […] You can almost feel the warm breath of the brown river beyond the river warehouses with their faint redolences of bananas and coffee.’ This is the Vieux Carré, or French Quarter of New Orleans, indeed the street on which the building sits, Elysian Fields, is named after the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris. Perhaps gives the sense of a place both within and outwith America – its ‘melting-pot’ atmosphere should suggest what is best about the country, and Williams notes that ‘New Orleans is a cosmopolitan city where there is a relatively warm and easy intermingling of races in the old part of town.’ (p.115) Such intermingling foregrounds the intermingling of blood that has gone on between Stanley (a ‘Polack’), and Stella (of high-bred, French Huguenot ancestry). Williams called this area of New Orleans ‘[t]he last frontier of Bohemia. A place in love with life.’ From the 1920s onwards, the French Quarter of New Orleans was home to many writers, artists, and musicians, and before that it is generally regarded as the birthplace of the blues and of jazz – a blend of African harmonies and rhythms and European instrumentation, and the soundtrack to A Streetcar Named Desire: from the ‘blue piano’ which sounds at the beginning and then throughout, to the ‘hot trumpet and drums’ which are most prominent at the end of scene ten when Stanley takes Blanche into the bedroom. In addition, Williams includes other characters who are also immigrants: the Mexican woman, Pablo Gonzales, and the Hubbel couple all come from different parts of the world. Williams wants us to consider New Orleans is a place of almost intoxicating sensuality: looking at the sky ‘attenuates the atmosphere of decay’; Williams suggests that we can ‘almost feel the warm breath of the brown river’; we can smell the bananas and coffee; and hear the sound of the ‘blue piano’. Class and the South It seems quite possible that Streetcar’s concerns with death derive in part from the turmoil of the recent world war, and that the clash of old and new civilisations in the play mirror the struggle that had been taking place between the old world of Europe and the new world of America. And America would soon take over from Europe as a superpower, as much of Europe began rebuilding. Yet there is also a personal strain here, since during 1946, Williams – who was a hypochondriac – believed that he was dying of pancreatic cancer (which he wasn’t). But he genuinely seemed to believe that Streetcar would be the last play he ever wrote. (See Donald Spoto, The Kindness of Strangers, p.139.) Such actions have lead some critics to see Blanche as a metatheatrical agent: playing a part, drawing attention to the costumes and props of the theatre, and even organizing the lighting of her face and body. This rather suggests an explicit connection between Blanche and Williams himself. According to Kazan, ‘Blanche DuBois, the woman, is Williams. […] Blanche DuBoisWilliams is attracted to the person who’s going to murder her… […] I saw Blanche as Williams, an ambivalent figure who is attracted to the harshness and vulgarity around him at the same time that he fears it, because it threatens his life.’ (p.139) Kazan’s sense of Williams’ deep involvement in the character is supported by one of the original titles for the play, ‘The Moth’, which suggests a creature that is attracted to its own destruction. We get a sense from Williams’s New Orleans of things being stripped back to their base elements. The possibility of new beginnings. This elemental quality is exemplified both by the primitive violence that we experience in the theatre when we see Stanley throw plates around the stage, and by the ritualistic chanting of the Mexican Woman, offering flowers for the dead. Blanche, who lives on elaborate illusions cannot cope with such a reduction to basic humanity and reacts by dressing herself up, trying to inhabit her illusions through alcohol, and placing paper shades over the lights to avoid having to look at reality. And it is the combination of two base and basic concerns of human existence, desire and death – the opposites which Blanche identifies for Mitch in scene nine – which seem to sum up the atmosphere of this part of New Orleans and much of the play. Given that, in Greek mythology, Elysium was the area of the Underworld described as the resting place for heroes or those of great moral virtue, the entry of Blanche into Elysian Fields – and the existence of Stanley within it – holds some considerable irony. Christopher Bigsby has noted that, ‘[a]s the twentieth century rushed away from it, the South became an aesthetic rather than a social fact.’ (‘Tennessee Williams: the theatricalising self’, in Modern American Drama, 1945-1990, p.48), and that in Blanche, ‘[t]he barren woman condemned to an asylum becomes a perfect image of the South.’ (‘Tennessee Williams: the theatricalising self’, p.50.) There is a direct contrast between Stella, who has accepted the new kind of society in which the aristocracy has lost all its power. In The Little Foxes, the character of Ben says that ‘the Southern aristocrat can adapt himself to nothing. Too high-tone to try.’ (The Little Foxes, Act One, p.157.) Whilst Blanche is associated with barrenness in the sense of her being first married to a gay man, and that she is childless, Stella on the other hand is about to have a baby. In The Little Foxes, Lillian Hellman showed how a newly ambitious and industrializing South had become a place where only the ruthless could survive, turning the old Southern values of hospitality and gentility into commodities to be bought and sold. In the tragic downfall of Blanche too – morally, physically, emotionally, mentally, Williams suggests that the old Southern values and identities have been destroyed, and replaced by characters like Stanley. Blanche (and perhaps the American audience) might like to see him as an invader, a ‘Polack’. In Scene One, Blanche says that Polish people are ‘something like Irish, aren’t they?’ (p.124), thereby showing both the limitations of her upbringing and her tendency to consider all immigrants to America in exactly the same way. However, as Stanley says so forcefully in scene eight, ‘a one hundred per cent American, born and raised in the greatest country on earth and proud as hell of it’. Given his actions towards Blanche and Stella during the play, this selfidentification raises difficult questions about American society. Are his actions representative of a typical American? Arthur Miller (who we meet next week,) said that Streetcar had a tremendous effect on him as he wrote Death of a Salesman. But it was ‘[n]ot the story or characters or the direction, but the words and their liberation, the joy of the writer in writing them, the radiant eloquence of its composition’. (See Miller’s autobiography, Timebends, p.182.) Miller saw in Streetcar a linguistic link with Europe, ‘the whole tradition of unashamed word-joy that, with the exception of Odets, we had either turned our backs on or […] used archaically’. (Timebends, p.182.) Things to consider What aspects of Stanley’s character and behavior make him particularly American? Support your ideas with at least two examples. Pick one of the alternative titles for the play, and explain why it might also have been suitable. ‘If [Williams] had written plays in the days before the technical development of translucent and transparent scenery, I believe he would have invented it. […] It was a true reflection of the contemporary playwright’s interest in – and at times obsession with – the exploration of the inner man. Williams was writing not only a memory play but a play of influences that were not confined within the walls of one room.’ (Quoted in Bigsby, A Critical Introduction to TwentiethCentury American Drama, v.2: Williams/Miller/Albee, pp.49-50.) o In what ways does Williams use the stage and stage effects to show the inner woman or memory of Blanche DuBois? o Pick one particular episode where the ‘play of influences’ is particularly obvious, and explain the effects of this combination. Pick out and explain two examples of imagery or symbolism that Williams uses which seem to encapsulate some of the key ideas in the play.