Spare a moment from the hurly burly outside, to take a leisurely stroll

advertisement

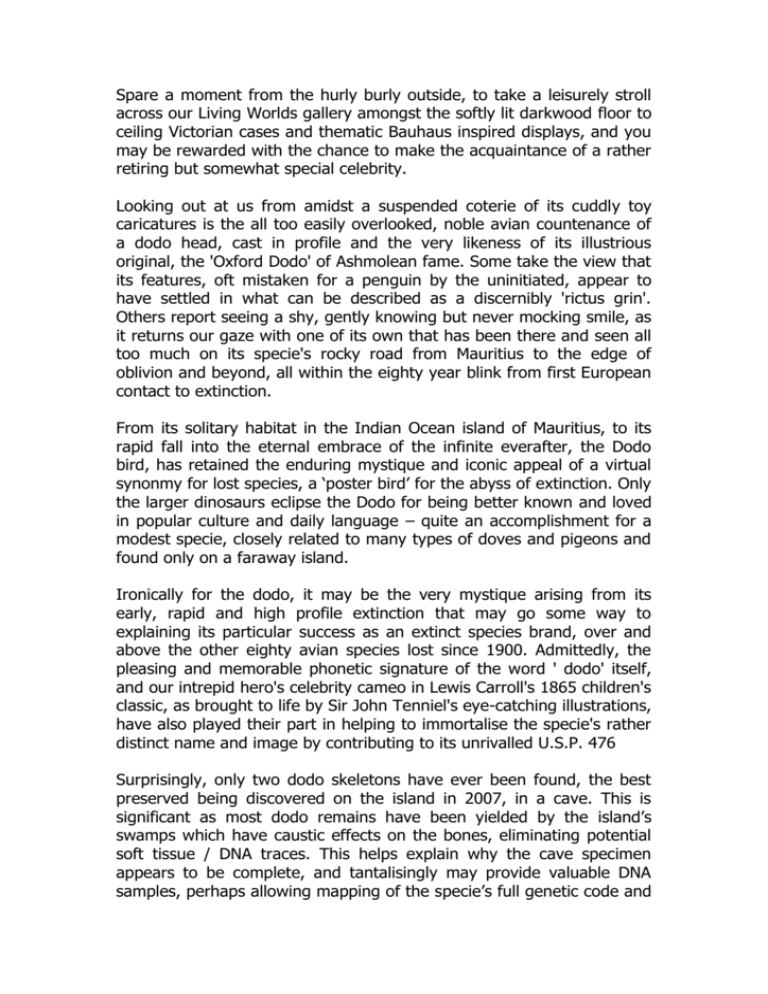

Spare a moment from the hurly burly outside, to take a leisurely stroll across our Living Worlds gallery amongst the softly lit darkwood floor to ceiling Victorian cases and thematic Bauhaus inspired displays, and you may be rewarded with the chance to make the acquaintance of a rather retiring but somewhat special celebrity. Looking out at us from amidst a suspended coterie of its cuddly toy caricatures is the all too easily overlooked, noble avian countenance of a dodo head, cast in profile and the very likeness of its illustrious original, the 'Oxford Dodo' of Ashmolean fame. Some take the view that its features, oft mistaken for a penguin by the uninitiated, appear to have settled in what can be described as a discernibly 'rictus grin'. Others report seeing a shy, gently knowing but never mocking smile, as it returns our gaze with one of its own that has been there and seen all too much on its specie's rocky road from Mauritius to the edge of oblivion and beyond, all within the eighty year blink from first European contact to extinction. From its solitary habitat in the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, to its rapid fall into the eternal embrace of the infinite everafter, the Dodo bird, has retained the enduring mystique and iconic appeal of a virtual synonmy for lost species, a ‘poster bird’ for the abyss of extinction. Only the larger dinosaurs eclipse the Dodo for being better known and loved in popular culture and daily language – quite an accomplishment for a modest specie, closely related to many types of doves and pigeons and found only on a faraway island. Ironically for the dodo, it may be the very mystique arising from its early, rapid and high profile extinction that may go some way to explaining its particular success as an extinct species brand, over and above the other eighty avian species lost since 1900. Admittedly, the pleasing and memorable phonetic signature of the word ' dodo' itself, and our intrepid hero's celebrity cameo in Lewis Carroll's 1865 children's classic, as brought to life by Sir John Tenniel's eye-catching illustrations, have also played their part in helping to immortalise the specie's rather distinct name and image by contributing to its unrivalled U.S.P. 476 Surprisingly, only two dodo skeletons have ever been found, the best preserved being discovered on the island in 2007, in a cave. This is significant as most dodo remains have been yielded by the island’s swamps which have caustic effects on the bones, eliminating potential soft tissue / DNA traces. This helps explain why the cave specimen appears to be complete, and tantalisingly may provide valuable DNA samples, perhaps allowing mapping of the specie’s full genetic code and heralding a host of new information about the Dodo. Across the passage of time, the global stage has many times been swept clear of the species that had long held sway, prior to our relatively brief time in the limelight, the dinosaurs again being the best known. We are privileged today to be able to snatch glimpses of many of these vanished species of flora and fauna, spanning the ancient through to the all too recent, through the refracted lens of scientific study painstakingly pieced together from the Victorian tangibilities of the fossil record and taxidermy, through to the virtualities of contemporary preoccupation with digital capture and genetic decoding. 100 However, such dramatic changes have been as a result of the universal processes of life itself, such as climate change, tectonic movements, major asteroid impacts. This is simply no longer the case. The rise of just one specie, ours, has changed the rules of the game as we continue to wield a grossly disproportionate impact on species and environments with unprecedented rates of habitat and species loss across the complexities of the planet's interwoven ecological webs. The tale of the humble dodo is most edifying for the way in which it quietly illustrates the early impact of these changes on one specie, and what they could spell for life on earth. The extinction of the dodo can be attributed to a single factor - human intervention: a wide range of predatory species including dogs, rats, pigs, monkeys, cats and others were introduced to Mauritius by early Dutch and Portugese explorers visiting the then uninhabited island. These species predated upon the birds or their eggs, which were conveniently laid on the ground, almost as a banquet. When crew and passengers made landfall fresh food was a priority and fuelled large scale hunting of the dodo, made all too easy due to its lack of both flight and fear, as it had evolved in a habitat where it had no predators. Large numbers may also have been hunted to be taken back for display, scientific specimens and curios. Within a single modern lifetime both the dodo and its eggs were hunted to extinction. The way in which the dodo was so swiftly and silently despatched, with little popular or scientific awareness or concern about its loss perhaps typified both attitudes to extinction up to the mid twentieth century, as well as how the drivers of change in the planet's biodiversity have shifted from extrinsic to anthropogenic. The dodo looking at us from behind the glass on our gallery, has seen much of it though not all: 'habitat change, loss and degradation', 'overexploitation', 'invasive alien species' all played their role in the dodo's early exit. However, its relatively early demise spared it the more recent drivers such as the rapid climate change, pollution, and introduced pathogens currently wielding the scythe for today's species. 339 The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was founded in 1948 as the world's first global environmental organisation and remains the largest to this day. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species connects the work of scientists and organisations from almost all nations to assess the relative risk of extinction across the species; to catalogue those plant and animal species which are moving towards extinction (i.e. those listed as Critically Endangered, Endangered and Vulnerable)using scientifically rigorous criteria; and to promote global awareness of their situation with a view to managing or reversing the risks posed. 96 A vibrant example of the potency of such international 'grass roots' cooperation in both raising public awareness and pioneering new conservation strategies, can be seen right here at Manchester Museum's state of the art Vivarium. Under Curator of Herpetology, Andrew Gray, the Vivarium works both on the ground in Costa Rica, Honduras and Guatemala through 'cutting edge' field work and research within habitats, alongside local people and partnerships as well as through the provision of free, accessible and informative 'live' displays, daily 'handling sessions', expert led tours, and a 'transparent' window onto the backstage laboratory areas. This provides accessible entry points for the public to make tangible, emotional connections with the species, their habitats and conservation status as well as promoting direct awareness and support for front line conservation efforts. Such global connectedness and co- operation gives us a powerful and positive message about just what we can, have and must do to protect the planet’s biodiversity and prevent too many other species from sharing the fate of the dodo looking out at us from the wrong side of a museum display case.