IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery

advertisement

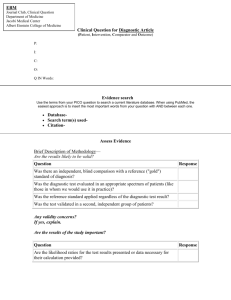

IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development Prepared for AIPLA’s MidWinter Institute for CLE Credits for a Panel Session Titled “IP Value for Personalized Medicine” 2:00 – 3:30 P.M., Thursday, January 31, 2013 Judith A. Roesler, Moderator Authors: Mark J. Stewart, Ph.D. Senior Director – Assistant General Patent Counsel Eli Lilly and Company Indianapolis, IN 46285 (317) 276-0280 stewart_mark@lilly.com Robert L. Sharp Patent Counsel Eli Lilly and Company Indianapolis, IN 46285 (317) 651-1541 sharp_robert_l@lilly.com Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Type of Discovery ................................................................................................................................ 2 III. Business Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 5 IV. Patentability and Infringement Considerations (US) ................................................................ 6 A. Divided Infringement ............................................................................................................................. 6 B. Patent Eligibility ....................................................................................................................................... 7 C. Inherency .................................................................................................................................................... 9 V. Patentability concerns outside the U.S.............................................................................................. 10 A. Article 53 Prohibitions........................................................................................................................ 10 B. Overlapping Patient Populations .................................................................................................... 12 C. Selection Inventions in the EPO ...................................................................................................... 12 VI. Partnering and Contracting Challenges ....................................................................................... 13 I. Introduction The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 along with rapid advances in technology associated with identifying and correlating markers with treatment outcomes necessitates that any company developing a new drug consider a biomarker strategy for such drug. At a conference on personalized medicine in 2007 John Lechleiter, Eli Lilly and Company’s CEO, stated that “the rise of personalized medicine is one of the most important developments in health care today. Personalized medicine will change health care almost across the board . . . But nowhere, I would argue, are the cross-currents of change more powerful or the stakes higher than in the development, manufacture, and sale of 1 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development prescription medicines. In my industry, we would be powerless to resist personalized medicine, not to say foolish.” FDA post-market surveillance along with public concerns related to the safety profile of a number of drugs is driving pharmaceutical companies to focus on tailored therapeutic initiatives. Tailored therapy is focused on tailoring the drug, dose, and dosing schedule to the appropriate patient population with the goal of improving individual patient outcomes with greater predictability. A tailored therapeutic focus involves an assessment of the spectrum of patient responses to a drug therapy and attempts to identity biomarkers that help stratify patient populations into groups with more predictable benefit/risk outcomes. This personalized medicine movement appears exciting and is clearly gaining ground; however, the initiative is rife with hurdles. One particular hurdle in supporting a tailored therapy approach to drug products relates to the fact that many – if not most - large pharmaceutical companies do not have the internal expertise to discover and then commercially develop companion diagnostics that will help identify the right patient, the right dose, and the right schedule. These companies must ultimately find partners with expertise in the appropriate diagnostic or technological area in order to sustain a successful personalized medicine approach. Relying on a diagnostic partner to develop a companion diagnostic that is potentially required in order to obtain approval of a drug significantly complicates an already complex drug development and approval process. Of course, a sound intellectual property strategy is part of that complicated process and central to the successful development and commercialization of a tailored therapeutic. IP strategy drivers for diagnostic related inventions include deep consideration of the following: 1) the type of discovery; 2) the business objectives and associated indirect as well as direct value propositions; 3) patentability and infringement considerations, especially in the US; and 4) the need to collaborate with third parties. II. The Type of Discovery Generally, the strength of patent protection is correlated with the type of discovery. Patent claims directed to the composition of matter are the strongest type of protection and would be available for the discovery of a novel biomarker. Such protection could be used, if desired, to exclude others from using the biomarker in any type of diagnostic for any type of drug. Myriad’s patents on the BRCA genes are examples of this type of protection.1 It remains to be seen, however, whether naturally existing genes and proteins are eligible for patent protection via a composition of matter claim.2 More likely is a discovery that a known marker or group of markers predicts response or dictates the course of therapy for a particular drug or class of drugs. This type of discovery may result U.S. Patent Nos. 5,747,282, 5,837,492, and 5,693,473 See Association for Molecular Pathology, et al. v. United States Patent and Trademark Office and Myriad Genetics. 2012 WL 3518509, ---F.3d--- (2012). 1 2 2 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development in method of treatment claims which can also be quite valuable especially if such methods read on a drug and/or diagnostic label claim. Generally, the first step in initiating a biomarker strategy is to find a biomarker or group of biomarkers that correlate with efficacy or some other treatment consequence of a particular drug. For example, the presence, absence, or level of a protein marker (e.g., lower or higher than “normal”) may indicate whether a particular drug will effectively and/or safely treat a particular disease in a distinguishable patient population. Identifying a biomarker or group of biomarkers that correlate with a particular drug treatment component more often than not does not involve the discovery of a previously unknown biomarker. In a more common scenario, the biomarkers are generally known proteins; however, their association with the particular drug being studied is unknown. The discovery is usually based on a retrospective analysis of pre-clinical or clinical trial samples taken from animals or patients that have been treated with a particular drug. The samples are screened for the presence of various known markers to determine whether any marker or subset of markers correlate with efficacy or some other treatment consequence. Often these types of discovery efforts are undertaken by the drug developer or involve some type of “fee for service” arrangement with a partner that does mostly “rule based” activities on a pay-as-you-go basis. Unless the partner has the ability to take a discovered correlation and develop that into a commercial companion diagnostic product, it is imperative that any arrangement involving intellectual property arising from the initial discovery give the drug developer the ability to partner and develop a companion diagnostic. Generally this means that the drug developer secures ownership or at least control of such IP. Interestingly, it is this initial “correlation” discovery that generates the most valuable (other than claims to the therapeutic composition or the specific use thereof) and potentially far-reaching IP as it can impact exclusivity for both the drug and the associated diagnostic. Method of treatment claims should be drafted with both the drug label and diagnostic label in mind. Drug labels can be general in nature or refer to specific “types” of assays. The following are three examples of drug labels going from general to more specific in terms of referencing assays: 1) the XALCORITM label states that the drug is indicated for the treatment of patients with locally advanced metastatic non-small cell lung cancer that is ALK-positive as detected by an FDA approved test;3 2) the HERCEPTINTM label states the detection of HER2 protein overexpression is necessary for selection of patients appropriate for Herceptin therapy. Due to differences in tumor histopathology use FDA-approved tests to assess HER2 protein overexpression AND HER2 gene amplification. Overexpression was tested using IHC and amplification was tested using FISH.4 3 4 http://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabeling.aspx?id=676 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/103792s5250lbl.pdf 3 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development 3) the ZELBORAFTM label states that the drug is indicated for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAFV600E mutation as detected by an FDAapproved test. In addition, the label notes that in clinical studies patients were tested using the cobas® 4800 BRAF V600 Mutation test which is designed to detect mutations in DNA isolated from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human melanoma tissue.5 For example, a method claim focusing on the drug label where a marker is identified and the directions are to use a FDA-approved test would consist of some variation of the following: A method of treating disease X in a patient, comprising testing for the presence of biomarker group Y in a biological sample from the patient and administering a therapeutically effective amount of Drug to the patient if the sample tests positive for biomarker group Y. A claim directed at a specific diagnostic assay would include limitations associated with how the presence of the biomarker is determined. Such claims can be extremely valuable as they have the potential to extend the exclusivity of the drug against generic competitors as any generic would be required to also include reference to the diagnostic test to meet FDA requirements. Companion diagnostic (CDx) labels that are associated with a FDA approved test or device will reference the companion drug. For example, the Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH probe test states that the “kit is a qualitative test to detect rearrangements involving the ALK gene via FISH in FFPE non-small cell lung cancer tissue specimens to aid in identifying those patients eligible for treatment with Xalcori® (crizotinib). This test is for prescription use only.”6 A method claim focusing on a diagnostic label that mentions a particular drug would consist of some variation of the following: A method of identifying patients with disease X eligible for treatment with Drug Z comprising testing a biological sample from the patient for the presence of biomarker Y, wherein the patient is eligible for treatment with Drug Z if biomarker Y is present. Less valuable are discoveries of assays and assay reagents as claims covering this type of subject matter do not generally impact the drug label and are usually easy to design around. The discovery and patenting of new platform technologies, however, can be extremely valuable to a diagnostic company with the capability of using such technology to bring companion diagnostics to market. With respect to considering proper claim scope in view of the assay(s) used to detect the presence, absence, or level of the biomarker(s), it is important to consider how a potential competitor may attempt to avoid patent infringement while at the same time demonstrating the equivalence of its device to a legally marketed device. A 510(k) is a premarket submission made to the FDA to demonstrate that the device to be marketed is substantially equivalent to a legally marketed device, the predicate. Substantial equivalence is established with respect to intended use, design, energy used or delivered, materials, chemical composition, manufacturing process, performance, safety, effectiveness, labeling, biocompatibility, standards, and other characteristics, as applicable. When drafting claims, it is important to consider other feasible methods or techniques for measuring the biomarker and include in the specification and/or 5 6 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202429s000lbl.pdf http://www.abbottmolecular.com/static/cms_workspace/pdfs/US/Vysis_ALK_FISH_Probe_Kit_PI.pdf 4 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development claims basis for reasonable alternative steps in order to account for the relative low hurdle for a 510(k) on a different, but “substantially equivalent,” diagnostic. III. Business Objectives Pharmaceutical companies must evaluate how to protect potential biomarkers throughout the drug development lifecycle. While there are some companion diagnostics developed late in the drug lifecycle, particularly to differentiate a late-stage or even launched product in the marketplace, most biomarkers are considered early in the development lifecycle. Unfortunately for these early development stage discoveries, at the time the initial discovery is made, it is completely unclear as to whether the discovery has commercial value and could lead to the development of a companion diagnostic. Furthermore, pharmaceutical companies without the core capability to commercially develop and sell diagnostic kits or assays are often conflicted as to whether to devote limited resources to file patents that may not necessarily extend the exclusivity for the drug product but instead relate primarily to such diagnostic kits and assays. The two overarching considerations that drive the IP strategy associated with a correlation invention discovered by a pharmaceutical company early in the drug product lifecycle are as follows: the drug developer must have freedom-to-operate in the use of the biomarker(s) for the clinical trials necessary for gaining approval of the drug; and if the use of the marker as a diagnostic is required by either a regulatory agency or a reimbursement agency, the drug developer must ensure the diagnostic is available to the health care provider or patient. Depending on the competitive landscape related to the drug, drug target and potential biomarkers, waiting to file a patent application until more data is generated and there is more certainty regarding the commercial value could be problematic. It is entirely possible that a competitor working with the same drug target could discover a biomarker correlation that, if patented, could create a freedom-to-operate risk. Freedom-to-operate risks can be mitigated either by publishing the relevant data or by filing a patent application. Although potentially more costly, filing a provisional application is the most efficient way to create prior art for a competitor that may make a similar discovery in the future. In addition, the commercial value of the invention can be reassessed within the provisional year and the application can be updated during that time as well. If a PCT application is filed at the year date, the owner has an additional 18 months to assess the value before spending more resources to prosecute the patent globally. Finally, to ensure that, if required, a diagnostic can be made available to the healthcare provider or patient, a diagnostic assay kit must be commercially developed and approved by the FDA. A partner may be unwilling to devote resources to what will be perceived as an extremely risky business proposition without some assurance of exclusivity should both the drug and companion diagnostic be successful. Without patent protection ensuring a diagnostic partner of exclusivity for a proposed diagnostic, pharmaceutical companies will be forced to pay significantly more to cover the partner’s risk of competing diagnostics in the marketplace. 5 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development IV. Patentability and Infringement Considerations (US) Although the patent law should be applied consistently across all technologies, the unique nature of biomarker-related inventions has raised some interesting legal issues in terms of how traditional legal principles should be applied to such inventions. These issues include: 1) divided infringement; 2) patent eligibility; and 3) inherent anticipation. A. Divided Infringement The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently addressed the issue of whether a method claim can be infringed if the steps of the claim are not performed by a single entity.7 Method of treatment claims associated with biomarker correlations are especially susceptible to divided infringement issues as a claim may require that the steps be performed by a doctor or other caregiver (treating the patient by administering the drug) and a laboratory technician (performing an assay to detect a biomarker). Specifically, the Federal Circuit determined whether a defendant (hereinafter, “D”) may be held liable for induced infringement if the D has performed some of the steps of the claimed method and has induced other parties to commit the remaining steps (Akamai case),8 or held liable if a D has induced other parties to collectively perform all the steps of the claimed method, but no single party has performed all of the steps (McKesson).9 In a 6 to 5 opinion, the court held that “[i]nducement requires that the alleged infringer knowingly induced infringement and possessed specific intent to encourage another’s infringement. . . . It is enough that the inducer causes, urges, encourages, or aids the infringing conduct and that the induced conduct is carried out.”10 In Akamai, D will be liable for inducement if 1) D knew of plaintiff’s (hereinafter, “P”) patent; 2) D performed all but one of the steps of the method; 3) D induced a party to perform the final step; and 4) the party in fact performed the final step. In McKesson, the D can be held liable for inducement if 1) D knew of P’s patent; 2) D induced the performance of the steps of the method claimed in the patent (even if multiple parties were required to perform such steps); and 3) the steps of the claim were actually performed (by one or more parties). As “correlation” claims would generally be asserted based on 35 U.S.C. § 271(b)11 against a generic that copies a drug label wherein the label requires use of a companion diagnostic test to identify the appropriate patient population to treat or against a diagnostic company that references a specific test to be used in conjunction with the drug, such claims can be, and generally are, drafted such that more than one party is required to perform all the steps of the method. There are, however, reasons to also include claims that only provide steps that can be performed by a single party. The en banc decision in Akamai and Mckesson was a 6 to 5 split decision. The dissenters were primarily concerned with what is required for direct infringement 7 Akamai Technologies Inc., et al. v. Limelight Networks Inc. and McKesson Technologies Inc. v. Epic Systems Corp., (Fed. Cir. 2012) (En Banc). 8 Id. at 9. 9 Id. 10 Id. at 15. 11 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) states that “[w]hoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” 6 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development under § 271(a) and whether that requirement should carry through to § 271(b). In other words, one cannot win on an inducement theory unless there is direct infringement under § 271(a). The majority declined to address § 271(a) infringement leaving the single-entity rule intact to prove direct infringement. In doing so, they also imposed the “new” standard which differentiates “actual” infringement under § 271 (b) which is still a requirement from “actual” infringement under § 271 (a) which must comply with the single-entity rule. The en banc court decision was a six judge per curiam decision that not only changed the law, it generated two dissenting opinions supported by numerous Federal Circuit judges. Therefore, it is quite possible the Supreme Court will consider, and perhaps even reverse, the Federal Circuit on the issue of whether all the steps of a claimed method must be performed by a single entity to find induced infringement.12 Because of the lack of predictability with respect to the future direction of the divided infringement law in the U.S., and to maximize options in U.S. or O.U.S. infringement litigation, Dx method claims should be drafted to cover the situation where all the required claim steps are performed by a single entity as well as the situation where multiple entities perform all the steps of the claimed method.13 B. Patent Eligibility Correlation claims necessarily involve patent eligibility issues as the correlation itself will likely be considered a “natural principle.” This area of law is in a state of flux, but it is likely that method of treatment claims which include the step of administering a specific drug to treat a specific patient population will be eligible for patenting. In fact, the current USPTO guidelines specifically state: “a claim that recites a novel drug or a new use of an existing drug, in combination with a natural principle, would be sufficiently specific to be eligible because the claim would amount to significantly more than the natural principle itself.” However, method claims that can be performed by a single entity are generally more vulnerable to patent ineligibility issues than those that require multiple parties to perform all the steps - which is an additional reason for including both types of claims. Although “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas” are not patentable subject matter under § 101 of the Patent Act, Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U. S. 175, 185, “an application of a law of nature . . . to a known structure or process may [deserve] patent protection,” Id. at 187. But to transform an unpatentable law of nature into a patent eligible application of such a law, a patent must do more than simply state the law of nature while adding the words “apply it.” See, e.g., Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U. S. 63, 71–72. It must limit its reach to a particular, inventive application of the law. 12 Akamai Technologies Inc., et al. v. Limelight Networks Inc. and McKesson Technologies Inc. v. Epic Systems Corp., (Fed. Cir. 2012) (En Banc). 13 On December 28, 2012, certiorari petitions were filed in both McKesson and Akamai. Petitioners ask the Supreme Court to review and reverse the Federal Circuit’s holding that third party infringement liability can be found in the absence of direct infringement by any party under 35 U.S.C. 271(a). A response is due February 4, 2013 in McKesson and a response in Akamai is due on February 1, 2013. 7 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development The Court has expressly noted that method of treatment claims are patentable subject matter in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 132 S. Ct. 1289, 1293 (2012); however, correlation claims that involve a “new” method of treatment using a drug known in the art may be susceptible to a challenge on § 101 grounds. The claim at issue in Prometheus was a method of optimizing therapeutic efficacy for treatment of an immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder that involves administering known drugs and then determining specific drug metabolite levels wherein certain levels indicate a need to increase or decrease the amount of drug administered. In its reasoning as to why this claim is ineligible for patent protection under § 101, the Court noted the drugs to be administered were well-known in the art and characterized the natural law as the relationship between metabolite levels and toxicity or effectiveness. The Court suggested that this “relationship exists in principle apart from any human action. The relation is a consequence of the ways in which thiopurine compounds are metabolized by the body – entirely natural processes. . . . A patent cannot merely recite a law of nature and then add the instruction ‘apply the law.’” Although it is difficult to discern a “test” that can be easily applied to determine whether a claim is patent eligible, the Court stated that the claim must encompass “something more” than the natural law and that if the “something more” is well understood, routine, conventional activity previously engaged in by researchers in the field – the claim is not eligible. Following Prometheus, the Federal Circuit revisited its decision in the case Association for Molecular Pathology, et al. v. United States Patent and Trademark Office and Myriad Genetics (“Myriad”). In that proceeding, the CAFC maintained its decision that the method claims with steps that involved “analyzing” sequences and “comparing” them were not patent eligible, but the method for screening potential cancer therapeutics was patent eligible as it involved growing transformed cells and determining the rate of growth of those cells. The Federal Circuit noted that, following Prometheus, just because a claim contains transformative steps it may still be ineligible if such transformative steps rely on natural laws. In this case, however, not only do the claims contain transformative steps but “at the heart of claim 20 is a transformed cell, which is made by man, in contrast to a natural material.” The method claims with the steps of “comparing” or “analyzing” two gene sequences were not patent eligible because they claim only abstract mental processes. The claims recite nothing more than the abstract mental steps necessary to compare two different sequences. It did not help that the claims were limited to BRCA genes primarily because Myriad’s claims do not apply the step of comparing two sequences in a process. “Rather the step of comparing two DNA sequences is the entire process that is claimed.” Although the Federal Circuit recently upheld the validity of the claims drawn to genes in Myriad, a petition for a writ of certiorai was granted by the Supreme Court on November 30, 2012. The patents before the Court claim isolated genes containing mutations that can be used to detect a patient’s predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer. The Court has agreed to consider the specific question of whether human genes are patentable. 8 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development The USPTO issued interim § 101 examination guidelines following the Prometheus case (See, http://www.uspto.gov/patents/law/exam/2012_interim_guidance.pdf). The guidelines apply to method claims which have a natural principle as a limiting step. The test applied is whether the “steps that integrate the natural principle into the claimed invention such that the natural principle is practically applied . . . are sufficient to ensure that the claim amounts to significantly more than the natural principle itself.” The USPTO, as well as the courts, include within the definition of a natural principle, a correlation that occurs naturally when a drug interacts with a naturally occurring substance, such as blood, “because even though it takes human action to trigger a manifestation of the correlation, the correlation exists in principle apart from any human action.” It is likely a correlation that involves correlating the presence of one or more markers with the ability of a drug to treat a disease is a natural principle. Thus, a claim that is limited only to the correlation such as a method of predicting whether a patient will respond to a particular drug that involves determining whether a marker is present is likely not eligible. The Office suggests that “the additional elements or steps must relate to the natural principle in a significant way to impose a meaningful limit on the claim scope. The analysis turns on whether the claim has added enough to show a practical application. In other words, the claim cannot cover the natural principle itself such that it is effectively standing alone.” The steps that impose a limit on the application of the natural principle must be “meaningful.” That is, such steps cannot simply amount to insignificant extra-solution activity. The USPTO guidelines provide the following example of what might amount to “extra-solution activity” and thus, fail to save the claim from ineligibility: “a claim to diagnosing an infection that recites the step of correlating the presence of a certain bacterium in a person’s blood with a particular type of bacterial infection with the additional step of recording the diagnosis on a chart.” Recording the diagnosis on a chart does not “save” the claim because it “does not integrate the correlation into the invention.” A claim to a new way of using an existing drug in the context of a discovered correlation (and clearly any method of using a new drug) will likely be patent eligible because the claim does not preempt every substantial practical application of the natural principle (e.g., the correlation). The USPTO guidelines specifically state: “a claim that recites a novel drug or a new use of an existing drug, in combination with a natural principle, would be sufficiently specific to be eligible because the claim would amount to significantly more than the natural principle itself.” C. Inherency Inherent anticipation should be considered when claiming a method of treatment involving administering a known drug for a known therapeutic purpose based on a previously unknown correlation with a biomarker or group of biomarkers. In the U.S., inherent anticipation cannot be established by probabilities or possibilities. The missing characteristic must be 9 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development “necessarily present, or inherent, in the single anticipating reference.”14 Thus, unless the correlation is absolute (meaning all patients with the biomarker respond or do not respond as the case may be), drafting claims directed to correlation inventions to avoid inherent anticipation should not be difficult. Inherent anticipation is of particular concern when a patent application claiming a correlation invention is filed later in the product life-cycle (for example, during or after phase III clinical trials) after a public disclosure of patients being treated with the drug. Thus, to address this particular inherent anticipation concern, the patent application should include claims that include a limitation associated with “selecting patients” based on performing “specific tests” to ensure novelty. V. Patentability concerns outside the U.S. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss patentability issues in all major jurisdictions, it is important to briefly discuss the law as it is evolving in Europe related to diagnostics especially because many jurisdictions outside of the U.S. generally follow the European approach to patentability. A. Article 53 Prohibitions In Europe methods of diagnosis practiced on the human or animal body are prohibited under Art. 53 EPC. The relevant portion of Article 53 states that European patents shall not be granted in respect of: “methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body; this provision shall not apply to products, in particular substances or compositions, for use in any of these methods.” Thus, when considering diagnostic method claims for Europe, it is important not to include the step of treating the subject with the drug. Alternatively, claims can be reformatted as second medical use claims. In addition, the Enlarged Boards of Appeal has issued a recent decision, G1/04, wherein the Board held that a claim is excluded from patentability only if it includes all the steps necessary to make a diagnosis – i.e.: 1. the diagnosis for curative purposes sticto sensu, representing the deductive medical or veterinary decision phase as a purely intellectual exercise; 2. the preceding steps which are constitutive for making that diagnosis – e.g. examination phase to collect the data; comparison of the data with standard values; and the finding of any significant deviation; and 3. the specific interactions with the human or animal body which occur when carrying those of the preceding steps which are technical in nature. 14 Schering Corp. v. Geneva Pharm., Inc., 339 F.3d 1373, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2003). 10 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development A common way of ensuring that the claim is not excluded as being a method of diagnosis is to omit the step of obtaining a sample from the subject and to start from the point at which the sample is already isolated. In addition, it is also useful to include dependent claims or literal language of the description to corresponding in vitro or non-invasive diagnostic methods. In contrast to the case law generated by the Prometheus case in the US, in Europe the claims were granted (see, EP1115403) on 14 December 2005 and were not opposed: Claim 1: An in vitro method for determining efficacy of treatment of a subject having an immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder or a non-inflammatory bowel disease (non-IBD) autoimmune disease by administration of a 6-mercaptopurine drug, comprising determining in vitro a level of 6-thioguanine in a sample from said subject having said immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder or said non-inflammatory bowel disease (non-IBD) autoimmune disease, wherein said treatment is considered efficient if the level of 6- thioguanine is in the range of about 230 pmol per 8 x 108 red blood cells to about 400 pmol per 8 x 108 red blood cells 15. The Myriad case (EP 699754) was upheld in amended form by the Technical Board of Appeal. Even though these claims are not technically “correlation” claims as discussed above, such claims are instructive as to what the EPO will consider as patentable Dx methods: 1. A method for diagnosing a predisposition for breast and ovarian cancer in a human subject which comprises determining in a tissue sample of said subject whether there is a germline alteration that is a frameshift mutation in the sequence of the BRCA1 gene coding for a BRCA1 polypeptide altering the open reading frame for SEQ ID NO:2 said alteration being indicative of a predisposition to said cancer. 2. A method for diagnosing a lesion of a human subject for neoplasia associated with the BRCA1 gene locus which comprises determining in a sample from said lesion whether there is an alteration that is a frameshift mutation in the sequence of the BRCA1 gene coding for a BRCA1 polypeptide altering the open reading frame for SEQ ID NO: 2, said alteration being indicative of neoplasia. 6. A method for diagnosing a predisposition for breast and ovarian cancer in a human subject which comprises determining whether there is germline alteration 5385insC in the BRCA1 gene in a tissue sample of said subject, said alteration indicating a predisposition to said cancer. For comparison, invalidated Claim 1 of Prometheus’ U.S. Patent No. 6,355,623 read: A method of optimizing therapeutic efficacy for treatment of an immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder, comprising: (a) administering a drug providing 6-thioguanine to a subject having said immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder; and (b) determining the level of 6-thioguanine in said subject having said immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorder, wherein the level of 6-thioguanine less than about 230 pmol per 8×108 red blood cells indicates a need to increase the amount of said drug subsequently administered to said subject and wherein the level of 6-thioguanine greater than about 400 pmol per 8×108 red blood cells indicates a need to decrease the amount of said drug subsequently ad ministered to said subject. 15 11 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development 7. A method for diagnosing a breast or ovarian lesion of a human subject for neoplasia associated with the BRCA1 gene locus which comprises determining whether there is mutation 5385insC in the BRCA1 gene in a sample from said lesion B. Overlapping Patient Populations If the patient population identified in the second medical use claim overlaps with the patient population in the prior art. The EPO Case law in this respect is not straightforward and includes contradicting cases which do not allow for clear guidance. The current Case Law of the EPO Technical Boards of Appeal suggests that if the patient population to be treated is clearly distinguishable with respect to its physiological or pathological status from the group previously treated the claim is novel16. However, if the patient population to be treated also potentially overlaps with the group previously treated, there is conflicting case law as to whether the claim is novel. In T 233/96 the Technical Boards of Appeal held that the treatment must be carried out on a novel group of subjects which is clearly distinguishable with respect to its physiological or pathological status from and does not overlap with the group previously treated to be novel. However, in the recent Decision T1399/0417, where T233/96 was also taken into account, the Technical Board of Appeal considered that the patient population was distinguishable from that disclosed in the prior art and the selection was of a specific patient group. Even though said patient population overlapped with the patient group disclosed in the prior art, the claim was still novel over that art. There has been significant discussion in the Pharma industry committees in respect of which approach the Examining Divisions at the EPO will be applied in future cases. If, for example, compound X is a known and approved drug for the treatment of disease X, and it is established that Biomarker A is present in a significant proportion of patients/population, the EPO considers that it is beyond reasonable doubt that at least one patient has been treated in the prior art and therefore the above claim is anticipated. There is still an argument that this type of claim is a selection invention (see below). For the time being, however, it appears the EPO will reject such claims and any arguments that the above type of claim constitutes a selection invention will have to be submitted to a Technical Board of Appeal. C. Selection Inventions in the EPO The current EPO Case law is consistent in requiring that the patient population selected is NOT an arbitrary selection. This is also consistent with selection invention criteria. Therefore a functional relationship must exist between the particular physiological or pathological status18 of this new group and the therapeutic effect obtained. In other words, the peculiar feature See sero-positive vs. Seronegative piglets (T 19/86) or haemophilic patient vs. normal, non-haemophilic subjects (T 893/90). 17 Similar approach was also taken in T 836/01 and T1642/06. 18 Referred to as a “different technical effect” in T 836/01 and “a new clinical situation” in T 836/01. 16 12 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development identifying the new group of patients must have a real impact on the result of the treatment, since it is able finally to "change" the treatment itself. VI. Partnering and Contracting Challenges For many pharmaceutical companies without a core diagnostic capability, once the initial discovery correlating a marker or set of markers to some aspect of treatment with a particular drug is made, it is necessary to find a partner to develop such discovery into a commercial product. The choice of partners is often extremely limited and depends on such things as: long term corporate stability; experience and competency in meeting regulatory requirements for the specific type of assay contemplated; the type of platform technology capability; global presence and ability to supply the market; exclusivity commitments with another party working on the same drug target; experience in the relative disease area; and finally intellectual property considerations. Once an appropriate partner is selected, the different business goals of the drug developer versus the diagnostic developer make contracting extremely difficult. The drug developer’s goal is to ensure that a diagnostic kit or assay is available to support clinical trials of a relevant drug and/or available to patients at the time of drug approval whereas the diagnostic developer’s goal is to maintain exclusivity for the kit or assay and receive direct value from the sale of kits or assays. The differential risk and reward propositions associated with bringing a drug to market versus a diagnostic to market also make contracting quite challenging. The role of IP in determining how the risk and reward propositions will be distributed is critical. IP considerations can be grouped into two categories. The first category deals with IP that each party brings to the table prior to negotiating a collaborative arrangement. The second category is associated with IP that is generated during and arising out of the collaboration by the parties either separately or jointly. Regarding the first category, the more typical scenario is one where the drug developer, either alone or with a different partner, has done initial screening of pre-clinical or clinical samples and has observed a relevant correlation with a marker or group of markers and a relevant aspect of treatment with a particular drug. If such a correlation is patentable as a method of treatment claim (see above), such patents can be extremely valuable as they may provide exclusivity for both the drug product and the diagnostic product. Thus, coming to the negotiation table with this type of IP may shift the risk/reward paradigm in a positive way towards the owner of such IP. Another common scenario is one where the drug developer, after screening patient samples and observing a correlation, seeks to develop an in vitro diagnostic assay that can form the basis for a commercial kit to be developed by a partner. For example, such initial assay work may involve discovering and optimizing antibody reagents for an immunoassay. Novel and inventive reagents might also form the basis for additional intellectual property. If such reagents are valuable to a potential diagnostic partner, the drug developer may retain more value and control. Generally, the diagnostic developer will come to the negotiation with IP covering various aspects of its platform technology. This is only indirectly important to the drug developer. If the platform technology is particularly desirable and the diagnostic company has relevant IP that has 13 IP Considerations Associated with Companion Diagnostic Discovery and Development the effect of limiting potential partners, the diagnostic company can leverage this fact during negotiations. The primary consideration for the drug developer is not whether the diagnostic company has a strong IP position related to its platform technology but rather whether the diagnostic company has freedom-to-operate when using such technology. Therefore, there is generally very little IP that a diagnostic company can bring to the table to enhance its negotiation position if the initial correlation discovery is made by the drug developer. Thus, the initial IP position has the potential to shift the paradigm from a true collaborative risk sharing relationship to one that is closer to a fee for service type of relationship. The reality, however, is that because there are generally a limited number of partners with the appropriate capabilities, these diagnostic companies have enough leverage to negotiate a collaborative risk sharing arrangement. The second category relates to IP arising out of the drug developer and diagnostic developer collaboration. Generally, the drug company is interested in controlling through ownership or exclusive licensing, any IP that relates to the drug product whereas the diagnostic company is interested in controlling IP that relates to the diagnostic and general platform technology. The difficulty with this type of an arrangement is that it is possible that IP could be generated where there is not a clear separation between drug and diagnostic related IP. A particular patent filing for example could relate to both the drug and the diagnostic (see discussion of method of treatment claims above). While co-ownership is a possibility, drug companies would want to prevent diagnostic companies from licensing competitors in the drug space and/or enforcing such a patent against a competitor’s drug and the diagnostic company would have similar concerns in the diagnostic space. Further, neither party is interested in being pulled into litigation it has not initiated which is virtually guaranteed with a patent that is coowned. These issues are difficult to work through. Relying on inventorship being determinative of ownership and ensuring that if one party has sole ownership, the other party at least has a nonexclusive license with the right to sublicense in the relevant space (e.g., drug or diagnostic) may solve certain scenarios where the IP relates to both the drug and diagnostic and the inventor or inventors are all employed by one company or the other. A further complicating factor relates to ownership and licensing of IP should the collaboration terminate prematurely. For example, if the diagnostic company fails to develop or is unable to adequately supply the market place, the drug company may be forced to find another partner and may need access to diagnostic company’s IP. Business deal structures in this area are still not well developed. Drug companies are resistant to sharing drug revenue yet may be unable to launch a drug without the co-development of a companion diagnostic. Diagnostic companies make money selling the diagnostic on the order of tens of millions yet those sales are almost entirely dependent on the success of the drug. 14