LESSON THREE CHINA TO 1985 Communism in post

advertisement

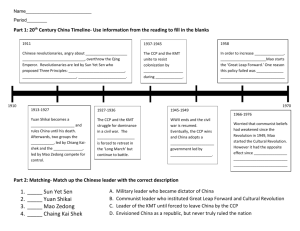

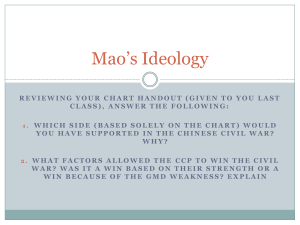

LESSON THREE CHINA TO 1985 Communism in post-war China had different roots from that in the Soviet block and followed a very different course. When in 1945 the war with Japan ended, US negotiators tried to effect a reconciliation between the nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek, and the communist Mao Tse-tung. The following spring, when Soviet forces evacuated Manchuria, a full-scale civil war broke out between communists and nationalists. Early victories persuaded Chiang that he could smash communism. In April 1948 he was appointed president by a new national assembly. The communists worked to achieve the support of the peasantry (peasant), and their army swelled in number. In late 1948 the nationalists were defeated in Manchuria, and by September 1949 the nationalist cause had collapsed. Mao Tse-tung became head of a new communist republic in October 1949. Chiang fled to Taiwan. In 1949 the Communist Party set up a "democratic dictatorship" under Mao. Although other parties were tolerated, the communists dominated. The 4.5 million party members grew to 17.5 million in 1961 (and 46 million in 1988). The first priority was agriculture. (real estate) In September 1950 an Agrarian Reform Law was announced, under which 300 million peasants benefited from the redistribution of 700 million mou(equal to one sixth of an acre) of landlord estates. By 1957 the villages were collectivized, pooling resources but retaining private ownership. The slow pace of change encouraged Mao to gamble on what became known as the Great Leap Forward. Launched in February 1958, it was a programme to modernize China in three years, based around the Maoist concept of the people's commune. 1 By November 1958 the countryside was organized into 26,000 communes, each responsible for abolishing private ownership and charged with delivering immense (and entirely unrealistic) increases in agricultural and industrial output. It was the age of the "backyard furnace", when 600,000 miniature blast furnaces were set up across China's villages and towns. The Great Leap Forward was a grotesque failure: economic output declined sharply; a severe famine killed 20 million. Mao, who had stood down as chairman of the republic in 1959 to concentrate on developing his ideological input to the revolution, found himself isolated by moderate elements in the party, led by Liu Shao-ch'i, who wanted to replace Maoist Utopias with socialist realism on the Soviet model. In 1961, despite Mao's fears that the Party was being taken over by a bureaucratic, revisionist elite, the Great Leap Forward was abandoned. Undeterred, in 1966, in alliance with the army and its leader, Lin Piao, Mao introduced a second revolutionary wave. Supported by enthusiastic young communists who shared Mao's fear that the revolutionary tide was ebbing, and who faithfully followed The Thoughts of Chairman Mao, (a collection of Mao's revolutionary beliefs, distributed by the million), Mao encouraged violent rooting out of deviationists. His wife, Chiang Ch'ing, led the Cultural Revolutionary Committee, which was responsible for imposing Maoist conformity and committed endless atrocities in the name of ideological purity. In 1968 the violence was threatening the complete collapse of Chinese life. Lin Piao was called on by Mao to restore order. The following year a party congress unanimously elected Mao party chairman and The Thoughts of Chairman Mao were adopted as the official party line. Lin Piao was groomed as Mao's successor and the army came to play a prominent part in national politics. Once again Mao feared for his political position. In 1970 he isolated Lin politically, and in 1971 foiled an attempted military coup, which ended with Lin Piao's death in September in a plane crash in Outer Mongolia. Mao, now a sick man, was unable to prevent his young and ambitious wife and her allies on the Cultural Revolutionary Committee from continuing a radical Maoist course. When Mao died on9 September 1976, Chiang and her "Gang of Four" tried to seize control of the state. By 1976 the army and much of the elite had had enough of ultra-leftism. Chiang and her coconspirators were arrested, tried and expelled from the party. A more moderate leadership, keen to pursue economic modernization, emerged under Hua Guofeng. Thanks to detente with the US, which in October 1971 led to China's entry to the United Nations, China was able to base her modernization on closer links with the international community. In 1978 the Cultural Revolution was officially declared at an end. In the 1980s China began to unravel the legacy of Maoist oppression and economic mismanagement. PART TWO – CHINA AFTER MAO Following the death of Mao, in1979 China embarked on economic reforms. Initially intended as modest changes to the command economy inherited from the Maoist era, these have in time turned into a transition toa market economy. Ushered in by Deng Xiaoping, within the first five years the reforms accomplished a complete decollectivizationof the rural economy, the opening wide of China toforeign trade and investment and the beginnings of aradical transformation of the state industrial sector. In 1980 the government created four Special Economic Zones (SEZ) close to Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan (Hainan became the fifth in 1988). The SEZs are special administrative zones offering a package of inducements to attract foreign direct investment. Between 1978 and 1998 China's annual GNP growth rate averaged over 9.5per cent. Exports grew 19-fold from 9.8 billion in 1978 to $182.7 billion in1997, making China the 10th largest trading country. Foreign direct investment soared from $1.7 billion in 1985 to $45.3 billion in 1997. In the countryside, collectively owned land was parcelledout from 1979 to households on 15 to 20-year leases, which have since been renewed. By 1984 almost all land wasfarmed by 2 households and within six years farm output had grown by 52.6 per cent. The reform of the state industrial sector began in 1984, and, in contrast to that of the rural economy, has been tortuous and remains to be finished. Though state enterprises remain important, Chinese industry is now diverse in terms of ownership and China is in effect no longer a planned economy. Notwithstanding its successes, the Chinese economy faces major problems of loss-making state enterprises, rising urban unemployment, the need to provide jobs for surplus rural labourers and large regional disparities in wealth. Political reform, although not absent, has lagged behind economic reform. Formally the oneparty state remains intact but under pressure from social changes. The period since 1979 has alternated between a loosening and a tightening of political control and the ideological straitjacket. With the passing of the Maoist era, 1978-9 saw the emergence of demands for a "Fifth Modernization" - democracy - to accompany the Four Modernizations of the economy and science and technology. The "Democracy Wall" with posters of uncensored expressions was shut down and its leader Wei Jinsheng sentenced to 15 years im prison. Following a loosening of political control and the criticism of the Party by the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi, in 1986 there were demonstrations in 15 major Chinese cities demanding greater democracy, Deng Xiaoping, who earlier talked about political reforms, responded by clamping down hard. The party secretary general, Hu Yaobang, was sacked for his liberal views. The conservatives in the party launched an "Anti Spiritual Pollution" campaign to counter the seeping effects of "bourgeois" liberalism. Hu Yaobang's death in April 1989 acted as the catalyst for demonstrations against corruption and for political reform. Supported by the general public, students occupied Tiananmen square. Demonstrations ended with the sending in of the army in Peking on 4 June and led to the dismissal of the then general secretary of the party, Zhao Ziyang, and the appointment of Jiang Zemin. In the run-up to the 10th anniversary in 1999, the nervous leadership arrested dissidents who tried to register new political parties. Following Tiananmen, economic reforms came to a halt. Fearing a reversal of economic reforms, in 1992 Deng Xiaoping launched a fresh round of economic liberalization which by accelerating the growth rate outflanked the conservative critics of liberalization. ba number of campaigns against corruption. The National People's Congress (China's Parliament), previously a rubber stamp, has grown in stature and begun to play a role in the formulation of laws while direct elections have been held for the choice of village leaders. Political change there certainly is, but it is still a long way from a well-functioning democracy. But if China has all the makings of a military super-power and an economic giant, it remains a developing country with a substantial percentage of its population living in dire poverty. 3 4