Mao Zedong`s Domestic Policies - Mr. O`Sullivan`s World of History

advertisement

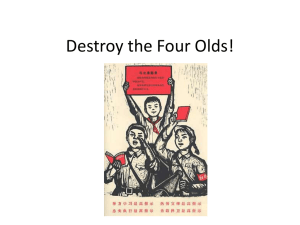

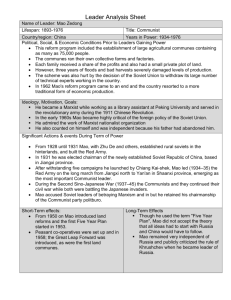

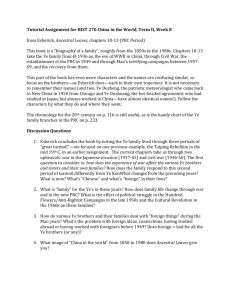

Mao Zedong’s Domestic Policies Education From the start of the PRC, there were aims to vastly improve education levels. Mao vowed that under Communism, China would see a large spread in education amongst the people, and a serious decrease in illiteracy. 1949 Most peasants were barely literate or completely illiterate, able to read little and write nothing. The literacy rate (people with basic reading and writing skills) stood at only 20% of a county populated by over 541 million people. By the middle of the 1950s a national system of primary education had been set up and led to the great increase in literacy that Mao had promised. By 1976 literacy now stood at 70%, a huge rise and a victory for Mao. Language Reform The PRC adopted a new reform of the Chinese language in 1955. They introduced a new form of written Mandarin (pinyin) to overcome the problem of differing pronunciation across China that meant that sometimes people couldn’t understand each other from region to region. This also helped the people of the PRC because previously their language had no alphabet. Despite these great victories for Mao, he did not have a completely positive effect on education in the PRC. In the last decade of his life all of the past achievements in education were worthless. A census compiled after his death showed these shocking statistics: • <1% of people had a university degree • 11% had received schooling after the age of 16 • 26% had received schooling between the ages of 1216 • And only 35% had received schooling after the age of 12! Embarrassingly for the Communist officials who succeeded Mao, they found that whilst Mao was in power only 6% of those responsible for running the government and the party had been educated beyond the age of 16. This may explain why the party’s ideas for modernising China were so unrealistic. The main reason for the decline in educated young people in China was, of course, the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) 130 million of China’s young people stopped attending school or university between 1966-70, and education was totally undermined during this period; pupils and students were encouraged to ridicule and beat their teachers, and reject all forms of traditional learning. Nothing was regarded as being of any real necessity any longer. Learning and study were dismissed as worthless unless they served the revolution, and it was seen as more important to train loyal party workers than to prepare China’s young people to take their place in a modern state. THEN Mao sent these rebellious young people “up to the mountains and down to the villages” in 1967-72 instead of insisting that they went back to school.