Ivabradine and Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure (SHIFT)

advertisement

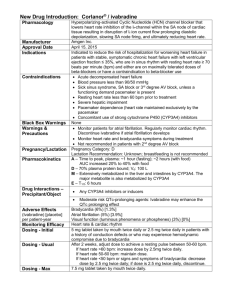

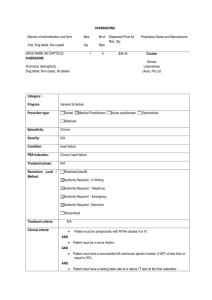

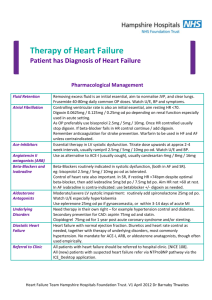

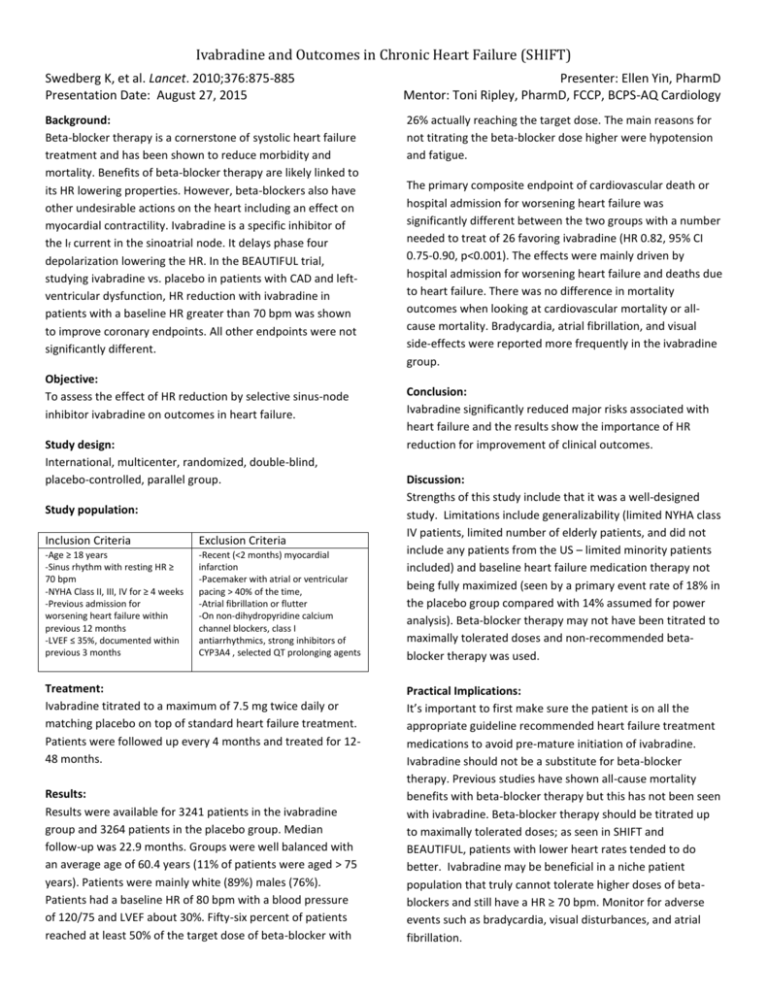

Ivabradine and Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure (SHIFT) Swedberg K, et al. Lancet. 2010;376:875-885 Presentation Date: August 27, 2015 Presenter: Ellen Yin, PharmD Mentor: Toni Ripley, PharmD, FCCP, BCPS-AQ Cardiology Background: Beta-blocker therapy is a cornerstone of systolic heart failure treatment and has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality. Benefits of beta-blocker therapy are likely linked to its HR lowering properties. However, beta-blockers also have other undesirable actions on the heart including an effect on myocardial contractility. Ivabradine is a specific inhibitor of the If current in the sinoatrial node. It delays phase four depolarization lowering the HR. In the BEAUTIFUL trial, studying ivabradine vs. placebo in patients with CAD and leftventricular dysfunction, HR reduction with ivabradine in patients with a baseline HR greater than 70 bpm was shown to improve coronary endpoints. All other endpoints were not significantly different. 26% actually reaching the target dose. The main reasons for not titrating the beta-blocker dose higher were hypotension and fatigue. Objective: To assess the effect of HR reduction by selective sinus-node inhibitor ivabradine on outcomes in heart failure. Study design: International, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group. Study population: Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria -Age ≥ 18 years -Sinus rhythm with resting HR ≥ 70 bpm -NYHA Class II, III, IV for ≥ 4 weeks -Previous admission for worsening heart failure within previous 12 months -LVEF ≤ 35%, documented within previous 3 months -Recent (<2 months) myocardial infarction -Pacemaker with atrial or ventricular pacing > 40% of the time, -Atrial fibrillation or flutter -On non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, class I antiarrhythmics, strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 , selected QT prolonging agents Treatment: Ivabradine titrated to a maximum of 7.5 mg twice daily or matching placebo on top of standard heart failure treatment. Patients were followed up every 4 months and treated for 1248 months. Results: Results were available for 3241 patients in the ivabradine group and 3264 patients in the placebo group. Median follow-up was 22.9 months. Groups were well balanced with an average age of 60.4 years (11% of patients were aged > 75 years). Patients were mainly white (89%) males (76%). Patients had a baseline HR of 80 bpm with a blood pressure of 120/75 and LVEF about 30%. Fifty-six percent of patients reached at least 50% of the target dose of beta-blocker with The primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or hospital admission for worsening heart failure was significantly different between the two groups with a number needed to treat of 26 favoring ivabradine (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75-0.90, p<0.001). The effects were mainly driven by hospital admission for worsening heart failure and deaths due to heart failure. There was no difference in mortality outcomes when looking at cardiovascular mortality or allcause mortality. Bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, and visual side-effects were reported more frequently in the ivabradine group. Conclusion: Ivabradine significantly reduced major risks associated with heart failure and the results show the importance of HR reduction for improvement of clinical outcomes. Discussion: Strengths of this study include that it was a well-designed study. Limitations include generalizability (limited NYHA class IV patients, limited number of elderly patients, and did not include any patients from the US – limited minority patients included) and baseline heart failure medication therapy not being fully maximized (seen by a primary event rate of 18% in the placebo group compared with 14% assumed for power analysis). Beta-blocker therapy may not have been titrated to maximally tolerated doses and non-recommended betablocker therapy was used. Practical Implications: It’s important to first make sure the patient is on all the appropriate guideline recommended heart failure treatment medications to avoid pre-mature initiation of ivabradine. Ivabradine should not be a substitute for beta-blocker therapy. Previous studies have shown all-cause mortality benefits with beta-blocker therapy but this has not been seen with ivabradine. Beta-blocker therapy should be titrated up to maximally tolerated doses; as seen in SHIFT and BEAUTIFUL, patients with lower heart rates tended to do better. Ivabradine may be beneficial in a niche patient population that truly cannot tolerate higher doses of betablockers and still have a HR ≥ 70 bpm. Monitor for adverse events such as bradycardia, visual disturbances, and atrial fibrillation. Ivabradine and Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure (SHIFT) Swedberg K, et al. Lancet. 2010;376:875-885 Presentation Date: August 27, 2015 Questions: 1. Do you agree with the FDA approval using the heart rate of 70 versus 77 as seen in the sub-group analysis? 1 Sub-group analyses are usually not powered for the primary outcome. Therefore, I believe it was appropriate for the FDA to approve ivabradine for patients with a HR ≥ 70 bpm based off the inclusion criteria. From a practicality standpoint, it also makes sense to use 70 bpm as the threshold. However, clinicians should also use clinical judgement to determine if adding ivabradine would be beneficial if a patient’s HR is between 70-77 bpm. 2. Given the bradycardia concern, should this agent be started inpatient or would you feel comfortable starting on an outpatient basis? 1 Patients should only be started on ivabradine if the baseline HR is ≥ 70 bpm. For patients in SHIFT, on average at 28 days after ivabradine initiation, the HR fell by about 10 bpm. Most patients should not experience bradycardia. Symptomatic bradycardia happened in about 5% of patients, while asymptomatic bradycardia happened in about 6% of patients with only 2% withdrawing from the study due to symptomatic or asymptomatic bradycardia. Therefore, I would feel comfortable starting the agent as an outpatient with frequent follow-up in patients with concern for bradycardia. 3. Would you start a patient on digoxin or this to reduce readmission for a patient with HFrEF? 1,2 When comparing SHIFT to DIG, digoxin led to a significant 15 (9-21)% relative risk reduction in the primary endpoint compared with a 18 (10-25)% relative risk reduction with ivabradine, both P<0.001. In both trials, the primary effect was on heart failure hospitalization without any significant effect on CV death. Heart failure hospitalization was reduced by 26 (17–34)% with ivabradine and by 28 (21–34)% with digoxin, both P< 0.001. The results of both trials are very similar although patients were not on beta-blocker therapy in the DIG trial (beta-blocker use not reported). Considering this, the decision to put patients on digoxin vs ivabradine should be patient specific. It depends on a patient’s comorbidities and insurance coverage. For example, if a patient has atrial fibrillation, digoxin would be a better choice for the patient. If a patient has renal dysfunction, ivabradine may be a better choice as it does not need to be renally adjusted. Cost, patient compliance, and drug/drug interactions should also be taken into account. It should also be noted that of the patients in SHIFT, 22% were already on cardiac glycosides. Presenter: Ellen Yin, PharmD Mentor: Toni Ripley, PharmD, FCCP, BCPS-AQ Cardiology 4. What is the perceived mechanism behind the increased risk of atrial fibrillation with ivabradine? 3,4 The molecular subunits of the If channel are the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide gated (HCN) channels. Several genetic alterations of the HCN channel gene have been reported to be associated with asymptomatic sinus bradycardia, sinus arrhythmia, and atrial fibrillation. Ruairidh et al. proposed that polymorphisms in the HCN4 locus, or other HR related loci, may affect the risk of atrial fibrillation on ivabradine treatment by changing the electrical activity in pulmonary vein myocytes. However, this is postulated using data extrapolated from rabbit studies. Atrial fibrillation is also common in patients with CAD and cardiac failure so incident atrial fibrillation cannot be completely pinpointed to drug administration. 5. How much weight do you give to the ‘death from heart failure’ outcome? 5 The validity of cause-specific mortality as an endpoint rests on the fundamental assumption that the cause of death can be determined accurately. The mode of death in patients with heart failure is frequently difficult to determine. An endpoint validation committee reviewed and adjudicated all pre-specified events according to definitions included in a charter. These definitions were not included in the main SHIFT article. When considering cause-specific mortality, the number of events is reduced, and this reduces the statistical power of the analysis to detect any difference between the treatment groups. When a difference is significant, the comparison can only be considered informative. A significant difference in a specific mode of death does not offset the lack of difference in all-cause mortality. 6. Regarding insurance coverage, what have people been required to prove in order to get coverage? 6 Ivabradine is a tier 3 drug on most insurance plans requiring prior authorization. According to Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, requests for ivabradine may be approved if the following criteria are met: ≥ 18 years AND NYHA class II, III, or IV heart failure symptoms AND LVEF ≤ 35% AND will be utilizing in combination with a beta-blocker OR has a contraindication or intolerance to beta-blocker therapy AND is in normal sinus rhythm AND has a resting HR ≥ 70 bpm. It may not be approved for any of the following: HR is maintained exclusively by a pacemaker OR severe hypotension (BP < 90/50 mmHg) OR severe hepatic impairment. Ivabradine and Outcomes in Chronic Heart Failure (SHIFT) Swedberg K, et al. Lancet. 2010;376:875-885 Presentation Date: August 27, 2015 Presenter: Ellen Yin, PharmD Mentor: Toni Ripley, PharmD, FCCP, BCPS-AQ Cardiology 7. Can you give examples of the ideal candidates for this medication? 1,7 The ideal candidate is a patient on all appropriate guideline recommended heart failure treatment medications at the target dose of beta-blocker but still has a resting HR ≥ 70 bpm with frequent hospital admissions for heart failure. Patients who cannot tolerate higher doses of beta-blocker therapy or have a contraindication to beta-blocker therapy such as severe asthma or COPD may also be a candidate for therapy. Also, based on results from the BEAUTIFUL and SIGNIFY trial, patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy may also benefit more from therapy. The hypothesis is that ischemic cardiomyopathy is characterized by loss of substantial quantities of myocardium through infarction which lead to irreversible scaring and limited potential for recovery whereas some or much of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy may be reversible. References: 8. Are there any sub-group analysis according to betablocker dose? 8 There was a subgroup analysis published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The primary endpoint and heart failure hospitalization were significantly reduced in all subgroups with <50% of target beta-blocker dose, including no beta-blocker (p=0.012). There was an apparent trend to reduction in treatment-effect magnitude with increasing beta-blocker dose. Across beta-blocker subgroups, treatment effect was borderline non-significant only for the primary endpoint and significance was further lost after adjusting for interaction between baseline heart rate and ivabradine effect. The authors concluded that the magnitude of heart rate reduction by beta-blocker plus ivabradine, rather than beta-blocker dose, primarily determines subsequent effect on outcomes. 1. Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al.; SHIFT Investigators. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomized placebocontrolled study. Lancet 2010;376:875-885. 2. The Digitalist Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997;336:525-533. 3. Cowie M. Ivabradine and atrial fibrillation: what should we tell our patients? Heart 2014; 100:1487-1488. 4. Ruairidh M, Oksana P, Mauro S, et al. Atrial fibrillation associated with ivabradine treatment: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart 2014; doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305482. 5. Zanolla L, Zardini P. Selection of endpoints for heart failure clinical trials. Eur J Heart Fail 2003; 5:717-723. 6. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. Rx prior authorization. Available at: https://www.anthem.com/pharmacyinformation /priorauth.html. Accessed Sept 13, 2015. 7. McMurray J. It is BEAUTIFUL we should be concerned about, not SIGNIFY: is ivabradine less effective in ischeaemic compared with non-ischaemic LVSD? Eur Heart J 2015: dio:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv190. 8. Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Effects on outcome of heart rate reduction by ivabradine in patients with congestive heart failure: is there an influence of beta-blocker dose? J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59:1938-45.