here - The Future of Just War

advertisement

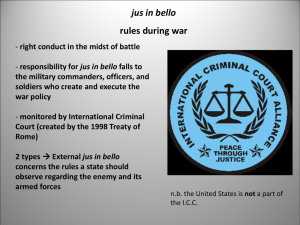

Does Just War Theory Rest on a Mistake? Adil Ahmad Haque Contemporary just war theory begins with Michael Walzer’s interpretation and defense of “the war convention,” of which the law of war is an integral part. Walzer argues that, just as the law of war grants combatants the legal right to kill in pursuit of an unjust cause, the war convention grants combatants the moral right to kill in pursuit of an unjust cause. Jeff McMahan would later respond that combatants have no moral right to kill in pursuit of an unjust cause. McMahan concludes that both the law of war and the war convention diverge from the deep morality of war. Moreover, McMahan concludes that the law of war *should* diverge from the deep morality of war, on the grounds that attempts to align the former with the latter will do little good but risk great harm. On this view, while the deep morality of war is concerned with the moral rights of each individual, the law of war should concern itself with reducing unjust harm overall. I will argue that both Walzer’s conventionalist view and McMahan’s revisionist view rest on a mistake. The law of war is not as they both assume, nor is the relationship between the law of war and the deep morality of war as either believes. Scott D. Sagan “Atomic Aversion and Just War Principles” To what degree does the American public support the just war doctrine principles of distinction (non-combatant immunity) and proportionality? In 1945, 85% of Americans approved of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and, indeed, 23% believed that the U.S. “should have quickly used many more bombs before Japan had a chance to surrender.” Were such views the result of the brutal violence of the Pacific War and the visceral hatred and racism the war produced? Or do these views reflect deeper beliefs about the priority of protecting American lives over foreign lives and a rejection of non-combatant immunity principles? I will report on a battery of new survey experiments that measure American public support or opposition to nuclear weapons use under a variety of realistic scenarios. The findings suggest that there is no belief in a “nuclear taboo” among the American public and that many Americans believe that mere political support for a government opposed to the United States makes foreign civilians legitimate targets in war. David Rodin ‘The Ethics of Revolutionary War’ This talk will address the ethics of revolutionary war in the context of contemporary Just War scholarship. Certain classical authors have argued that there are more stringent reasons to reject revolutionary war compared to other forms of war. I will argue that this is not the case, but there are nonetheless strong objections to revolutionary war and revolutionary violence more generally. Helen Frowe ‘Reductive Individualism and the Just War Framework’ Both traditional collectivist accounts of war and revisionist reductive individualist accounts of war employ the familiar distinction between jus ad bellum and jus in bello. I argue that reductive individualists cannot sustain a distinction between jus ad bellum and jus in bello. If these categories differ, they must either contain different moral principles, or evaluate different objects, or both. Since reductivism is the claim that there is a single set of moral principles that governs all uses of defensive force, and since ad bellum and in bello govern the use of defensive force, reductivists cannot hold that jus ad bellum and jus in bello differ in content. Some reductivists grant this, but argue that the terms nonetheless pick out different objects. Jus ad bellum governs the ‘war as a whole’; jus in bello governs individual actions or small groups of individual actions. I reject the claim that jus ad bellum offers us a useful summative assessment of the ‘war as a whole’. Both categories evaluate all the individual actions of a war as a means of determining the justness of specific individual actions, and it’s only the evaluation of those individual actions that is morally interesting. Thus, these categories do not differ in their objects, and we ought to reject the familiar just war framework. Jeff McMahan Against Collectivist Approaches to the Morality of War Perhaps the most common way of thinking about war is that it is, as Rousseau says, “something that occurs not between man and man, but between States.” According to this view, states and certain other collectives have interests, desires, goals, and intentions that are not reducible to those of individual persons. Collectives can also act in ways for which they are responsible and even blameworthy, again in ways that are not reducible to the responsibility or blameworthiness of individuals. This way of thinking about states in war leads naturally to a conception of soldiers as instruments through which states achieve their purposes rather than as responsible moral agents whose acts of killing must meet a high standard of moral justification. I will oppose this way of thinking about war and defend an individualist understanding of both states and war, according to which political leaders, soldiers, and civilian citizens are neither absolved of responsibility for their individual contributions to war nor made responsible for the contributions of others simply by virtue of their membership in a collective such as the state or the military.