Lecture 8: Walzer on Just War Theory

advertisement

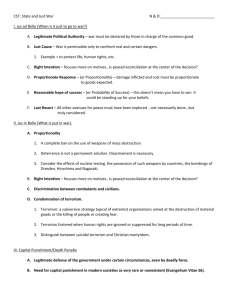

Lecture 8: Walzer on Just War Theory Ethics of Emerging Weapons Technologies February 7, 2013 Michael Walzer (1935–) Ad Bellum and In Bello • jus ad bellum: justice in the resort to war, the justice “of” war • jus in bello: justice in the conduct or means of war, justice in war Aggression War has human agents as well as human victims. Those agents, when we can identify them, are properly called criminals. Their moral character is determined by the moral reality of the activity they force others to engage in. They are responsible for the pain and death that follow from their decisions, or at least for the pain and death of all those persons who do not choose war as a personal enterprise. In contemporary international law, their crime is called aggression, and I will consider it later on under that name. But we can understand it initially as the exercise of tyrannical power, first over their own people and then, through the mediation of the opposing state’s recruitment and conscription offices, over the people they have attacked. (p. 31) Aggression: The Legalist Paradigm (ch. 4) • There exists an international society of independent states • This international society has a law that establishes the rights of its members – above all, the rights of territorial integrity and political sovereignty. • Any use of force or imminent threat of force by one state against the political sovereignty or territorial integrity of another constitutes aggression and is a criminal act. • Aggression justifies two kinds of violent response: a war of self-defense by the victim and a war of law enforcement by the victim and any other member of international society. • Nothing but aggression can justify war. • Once the aggressor state has been militarily repulsed, it can also be punished. Exceptions to the Legalist Paradigm Anticipation, Preventative War, or Preemptive Strike (ch. 5) To say that [there are legitimate preemptive strikes], however, is to suggest a major revision of the legalist paradigm. For it means that aggression can be made out not only in the absence of a military attack or invasion but in the (probable) absence of any immediate intention to launch such an attack or invasion. The general formula must go something like this: states may use military force in the face of threats of war, whenever the failure to do so would seriously risk their territorial integrity or political independence. Under such circumstances it can fairly be said that they have been forced to fight and that they are the victims of aggression. (p. 85) Exceptions to the Legalist Paradigm Anticipation, Preventative War, or Preemptive Strike (ch. 5) The line between legitimate and illegitimate first strikes is not going to be drawn at the point of imminent attack but at the point of sufficient threat. That phrase is necessarily vague. I mean it to cover three things: a manifest intent to injure, a degree of active preparation that makes that intent a positive danger, and a general situation in which waiting, or doing anything other than fighting, greatly magnifies the risk. (p. 81) Exceptions to the Legalist Paradigm Intervention in Other Conflicts (ch. 6) Self-determination, then, is the right of a people “to become free by their own efforts” if they can, and nonintervention is the principle guaranteeing that their success will not be impeded or their failure prevented by the intrusions of an alien power. It has to be stressed that there is no right to be protected against the consequences of domestic failure, even against a bloody repression. (p. 88) Exceptions to the Legalist Paradigm Intervention in Other Conflicts (ch. 6) • when a particular set of boundaries clearly contains two or more political communities, one of which is already engaged in a large-scale military struggle for independence; that is, when what is at issue is secession or “national liberation,” • when the boundaries have already been crossed by the armies of a foreign power, even if the crossing has been called for by one of the parties in a civil war, that is, when what is at issue is counter-intervention; and • when the violation of human rights within a set of boundaries is so terrible that it makes talk of community or self-determination or “arduous struggle” seem cynical and irrelevant, that is, in cases of enslavement or massacre. (p. 90) “Excessive” Harm (ch. 8) What is being prohibited here is excessive harm. Two criteria are proposed for the determination of excess. The first is that of victory itself, or what is usually called military necessity. The second depends upon some notion of proportionality: we are to weigh “the mischief done,” which presumably means not only the immediate harm to individuals but also any injury to the permanent interests of mankind, against the contribution that mischief makes to the end of victory. (p. 129) Military Necessity (ch. 8) The doctrine justifies not only whatever is necessary to win the war, but also whatever is necessary to reduce the risks of losing, or simply to reduce losses or the likelihood of losses in the course of the war. In fact, it is not about necessity at all; it is a way of speaking in code, or a hyperbolical way of speaking, about probability and risk. [. . . ][T]here will always be a range of tactical and strategic options that conceivably could improve the odds. There will be choices to make, and these are moral as well as military choices. (p. 144) Proportionality (in bello) (ch.8) Once again, proportionality turns out to be a hard criterion to apply, for there is no ready way to establish an independent or stable view of the values against which the destruction of war is to be measured. Our moral judgments wait upon purely military considerations and will rarely be sustained in the face of an analysis of battle conditions or campaign strategy by a qualified professional. (p. 129) The Violation of Human Rights (ch. 8) A legitimate act of war is one that does not violate the human rights of the people against whom it is directed. [. . . ] Everyone else [who is not a soldier fighting in a war] retains his rights, and states remain committed, and entitled, to defend those rights whether their wars are aggressive or not. But now they do this not by fighting but by entering into agreements among themselves, by observing these agreements and expecting reciprocal observance, and by threatening to punish military leaders or individual soldiers who violate them. (pp. 135–136) Discrimination (ch. 9) The war convention rests first on a certain view of combatants, which stipulates their battlefield equality. But it rests more deeply on a certain view of noncombatants, which holds that they are men and women with rights and that they cannot be used for some military purpose, even if it is a legitimate purpose. (p. 137) Double Effect (ch. 9) 1 The act is good in itself or at least indifferent, which means, for our purposes, that it is a legitimate act of war. 2 The direct effect is morally acceptable – the destruction of military supplies, for example, or the killing of enemy soldiers. 3 The intention of the actor is good, that is, he aims only at the acceptable effect; the evil effect is not one of his ends, nor is it a means to his ends. 4 The good effect is sufficiently good to compensate for allowing the evil effect; it must be justifiable under [proportionality]. (p. 153) Doctrine of Double Intention (ch. 9) 1 The act is good in itself or at least indifferent, which means, for our purposes, that it is a legitimate act of war. 2 The direct effect is morally acceptable – the destruction of military supplies, for example, or the killing of enemy soldiers. 3 The intention of the actor is good, that is, he aims narrowly at the acceptable effect; the evil effect is not one of his ends, nor is it a means to his ends, and, aware of the evil involved, he seeks to minimize it, accepting costs to himself. 4 The good effect is sufficiently good to compensate for allowing the evil effect; it must be justifiable under [proportionality]. (pp. 153, 155) Guerrilla Warfare (ch. 11) [T]he guerrillas don’t subvert the war convention by themselves attacking civilians. . . Instead, they invite their enemies to do it. By refusing to accept a single identity [i.e., soldier or civilian], they seek to make it impossible for their enemies to accord to combatants and noncombatants their “distinct privileges. . . and disabilities.” (pp. 179–180) Guerrilla Warfare (ch. 11) Indeed, it is more plausible to make exactly the opposite argument: that the war rights the people would have were they to rise en masse are passed on to the irregular fighters they support and protect – assuming that the support, at least, is voluntary. For soldiers acquire war rights not as individual warriors but as political instruments, servants of a community that in turn provides services for its soldiers. (p. 185) Guerrilla Warfare (ch. 11) Have these civilians forfeited their immunity? Or do they, despite their wartime complicity, still have rights vis-a-vis the anti-guerrilla forces? [. . . ] We must imagine a domestic state of emergency and ask how the police might legitimately respond to such hostility. Soldiers can do no more when what they are doing is police work; for the status of the hostile civilians is no different. Interrogations, searches, seizures of property, curfews – all these seem to be commonly accepted; but not the torture of suspects or the taking of hostages or the internment of men and women who are or might be innocent. (pp. 185–188) Terrorism (ch. 12) In its modern manifestations, terror is the totalitarian form of war and politics. It shatters the war convention and the political code. It breaks across moral limits beyond which no further limitation seems possible, for within the categories of civilian and citizen, there isn’t any smaller group for which immunity might be claimed. Terrorists anyway make no such claim; they kill anybody. (p. 203) Terrorism (ch. 12) The mark of a revolutionary struggle against oppression, however, is not this incapacitating rage and random violence, but restraint and self-control. The revolutionary reveals his freedom in the same way as he earns it, by directly confronting his enemies and refraining from attacks on anyone else. It was not only to save the innocent that revolutionary militants worked out the distinction between officials and ordinary citizens, but also to save themselves from killing the innocent. [. . . ] The same thing can be said of the war convention: in the context of a terrible coerciveness, soldiers most clearly assert their freedom when they obey the moral law. (pp. 205–206) Jus ad bellum (1/2) • just cause: A state may launch a war only in resistance to aggression. Aggression is the use of armed force in violation of someone else’s basic rights. • right intention: A state must intend to fight the war only for the sake of its just cause. Ulterior motives, such as a power or land grab, or irrational motives, such as revenge or ethnic hatred, are ruled out. • formal declaration: A state may go to war only if the decision has been made by the appropriate authorities, according to the proper process, and made public, notably to its own citizens and to the enemy state. Jus ad bellum (2/2) • last resort: A state may resort to war only if it has exhausted all plausible, peaceful alternatives to resolving the conflict in question, in particular diplomatic negotiation. • probability of success: A state may not resort to war if it can foresee that doing so will have no measurable impact on the situation. • proportionality: A state must, prior to initiating a war, weigh the universal goods expected to result from it, such as securing the just cause, against the universal evils expected to result, notably casualties. Only if the benefits are proportional to, or “worth”, the costs may the war action proceed. Jus in bello (1/2) • discrimination: Soldiers are only entitled to use their weapons to target those who are “engaged in harm.” While some collateral civilian casualties are excusable, it is wrong to take deliberate aim at civilian targets. • military necessity: Only targets, even otherwise legitimate targets, which materially advance victory (i.e., the war’s just cause) may be attacked. • proportionality: Soldiers may only use force proportional to the end they seek. They must restrain their force to that amount appropriate to achieving their aim or target. • fair treatment of prisoners: If enemy soldiers surrender and become captives, they cease being lethal threats to basic rights. They are no longer “engaged in harm.” Thus it is wrong to target them with death, starvation, rape, torture, medical experimentation, and so on. Jus in bello (2/2) • preservation of human rights: Soldiers may not use weapons or methods which are “evil in themselves,” or which damage the basic human rights of those they target, even if legitimate targets. These include: mass rape campaigns; genocide or ethnic cleansing; using poison or treachery; forcing captured soldiers to fight against their own side; or using weapons whose effects cannot be controlled. • no reprisals: States may not violate jus in bello as a way to punish another state for a prior violation of jus in bello.