View/Open - Lirias

advertisement

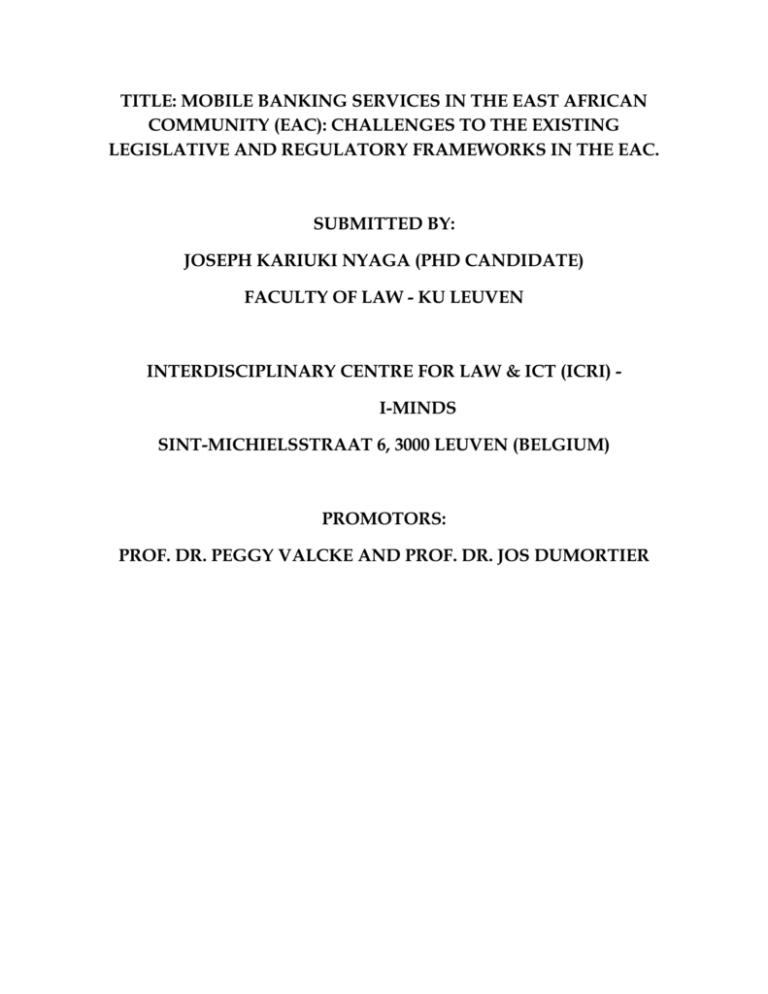

TITLE: MOBILE BANKING SERVICES IN THE EAST AFRICAN COMMUNITY (EAC): CHALLENGES TO THE EXISTING LEGISLATIVE AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS IN THE EAC. SUBMITTED BY: JOSEPH KARIUKI NYAGA (PHD CANDIDATE) FACULTY OF LAW - KU LEUVEN INTERDISCIPLINARY CENTRE FOR LAW & ICT (ICRI) I-MINDS SINT-MICHIELSSTRAAT 6, 3000 LEUVEN (BELGIUM) PROMOTORS: PROF. DR. PEGGY VALCKE AND PROF. DR. JOS DUMORTIER TABLE OF CONTENT: ABSTRACT:…………………………………………………………………………….. 3 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………… 3 1.1 Legal and institutional framework of the EAC……………………………… 3 1.2. Principal research question: …………………………………………………… 6 1.3. Aims and objectives of the research:………………………………………….. 6 1.4. Design/methodology/approach…………………………………………………..7 1.5. Synopsis…………………………………………………………………………… 7 2. MOBILE MONEY LANDSCAPE ACROSS THE EAC…………………….. 7 2.1. Mobile money players……………………………………………………………… 7 2.2. Types of mobile money transactions………………………………………………. 8 3. LEGISLATIVE AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS……………………10 3.1. Overview of the legislative and regulatory areas of relevance to Mobile Money:……………………………………………………………………………..11 3.2. Analysis of the legislative and regulatory issues to Mobile Money in the EAC:…………………………………………………………………………..…… 15 4. ENABLING ENVIRONMENT FOR MOBILE-BANKING GROWTH IN THE EAC 4.1. Dimensions affecting mobile-banking development in the EAC…………….. 19 4.2. Enabling principles for mobile-banking development in the EAC…….……..20 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………23 ABSTRACT: In the East African Community (EAC), mobile banking is growing at a remarkable speed and it is bound to further grow in a significant way in the near future. The field of mobile-payments and mobile-banking is not only new and fast evolving in the EAC but also sits at the overlap of several regulatory and legislative domains—those of banking and telecommunication. The overlap substantially raises the risk of coordination failure, where legislation or regulatory approaches are inconsistent or contradictory. This is creating considerable uncertainty about the appropriate regulatory response that must be established and also what supervisory regime applies to the various activities involving banks and non-banks. A comprehensive vision for market development between policy makers, regulators and industry players in the EAC can help to define the obstacles and calibrate proportionate responses to risk at appropriate times. This paper therefore addresses regulatory and legislative issues affecting mobile money in the EAC, where cell phones transfer more than half a billion dollars monthly. The number of mobile phone users has long exceeded the number of people with bank accounts across the EAC. The purpose is therefore to demonstrate the need for the EAC to address issues relating to telecommunications and financial regulation to ensure that mobile money services bring the desired broad benefits, especially to the poor in the EAC. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Legal and institutional framework of the EAC The East African Community (EAC) is the regional intergovernmental organisation of the Republics of Kenya, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, Republic of Burundi and Republic of Rwanda with its headquarters in Arusha, Tanzania. The Treaty for Establishment of the East African Community was signed on 30th November 1999 and entered into force on 7th July 2000 following its ratification by the Original 3 Partner States – Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. The Republic of Rwanda and the Republic of Burundi acceded to the EAC Treaty on 18th June 2007 and became full Members of the Community with effect from 1st July 2007. The aims and objectives of the EAC include widening and deepening co-operation among the Partner States in, among others, political, economic and social fields for their mutual benefit.1 To this 1 Article 5 of the EAC Treaty. Available at: http://www.eac.int/home.html extent, the EAC countries established a Customs Union in 2005 and a protocol on a Common Market took effect on the 1st of July 2010. The next phase of the integration will see the block enter into a Monetary Union and ultimately become a Political Federation of the East African States.2 The EAC’s institutional frameworks at the Community level include the following: 1. Summit which consists of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government whose function is to provide overall strategy and political direction. 2. The Council consisting of the Ministers responsible for regional co-operation of each Partner State whose function is to Coordinate and formulate policies. 3. The East African Court of Justice tasked to ensure adherence to law in the interpretation and application of and compliance with the EAC Treaty. The Court has jurisdiction over the interpretation and application of the Treaty and may have other original, appellate, human rights or other jurisdiction upon conclusion of a protocol to realize such extended jurisdiction. 4. The East African Legislative Assembly tasked with the Community legislative powers, any legislative decision by the assembly which is gazetted by Summit will supersede and take precedence over any other related national law. 5. The Secretariat headed by an appointed Secretary General.3 Currently, the regional integration process is at a high pitch at the moment as reflected by the encouraging progress of the East African Customs Union and the establishment in 2010 of the Common Market. The negotiations for the East African Monetary Union, which commenced in 2011, and fast tracking of the process towards East African Federation all underscore the serious determination of the East African leadership and citizens to construct a powerful and sustainable East African economic and political bloc.4 In the ICT sector, the EAC has seen a rapid growth of mobile telephony in the EAC. The establishment of the common market has led to increased competition in the sector. Mobile network operators (MNOs) are exploring new business opportunities and as a 2 See: http://www.eac.int/about-eac.html 3 Article 9 of the Treaty establishing the East African Community( hereinafter the EAC Treaty) 4 http://eac.int/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1:welcome-to-eac&catid=34:body-textarea&Itemid=53 result many new services are emerging. Mobile money is one of the most notable services of this trend. This is a phenomenon that took off in earnest only in the past few years with M-PESA5 which started operating in Kenya in 2007. M-PESA has taken the lead in terms of innovation for providing more inclusive access to finance a large part of the population who hitherto had been without a bank account. The EAC is therefore at the forefront of this trend.6 Mobile money is generally used here to refer to money stored using the SIM (subscriber identity module) in a mobile phone as an identifier as opposed to an account number in conventional banking. Notational equivalent is in value issued by an MNO and is kept in a value account on the SIM within the mobile phone that is also used to transmit transfer or payment instructions, while corresponding cash value is safely held elsewhere, normally in a bank for the case of EAC. The balance on the value account can be accessed via the mobile phone, which is also used to transmit instant transfer or payment instructions. Mobile money offers new possibilities for making financial services more inclusive in EAC and beyond. Unlike conventional banking and financial services, MNOs in the EAC have made huge investments to create networks that reach further and deeper into rural areas historically marginalised in an effort to satisfy their demand to communicate.7 As average revenue per user (ARPU) from traditional services decline, MNOs and their partners are looking at this network platform to offer new kinds of services. In addition, there is a wide range of cheap mobile phones making them affordable to a wider section of the population and a common artefact across the EAC. The rapid growth in mobile money has added urgency to the need for an effective and robust legal and regulatory framework in the EAC. Ordinarily, regulators and Governments in the EAC tend to look towards the developed world to draw examples from. But in the case of mobile money, the situation is the reverse. EAC region is at the forefront of the mobile money revolution with a number of implementations amongst the few that are gaining attraction globally and, as a result, has few examples to draw 5 m-pesa is a fast, safe and easy way to send and receive money with your cell phone. It is like having instant cash in your hand and you don’t even need a bank account. m-pesa lets you convert cash into mobile money and withdraw cash at any authorized m-pesa outlet. Once you have money in your m-pesa account, you can send it to anyone, anywhere in the EAC. You are also able to buy airtime for yourself and others. 6 See also Duncombe, R. and R. Boateng (2009). “Mobile Phones and Financial Services in Developing Countries: a review of concepts, methods, issues, evidence and future research directions.” Third World Quarterly 30(7): 1237 – 1258. | Porteous, D. (2006). “The Enabling Environment for Mobile Banking in Africa.” DFID. | Donner, J. and C. A. Tellez (2008). “Mobile banking and economic development: Linking adoption, impact, and use.” Asian Journal of Communication 18(4): 318-322. 7 Mas, I. and K. Kumar (2008). “Banking on Mobiles: Why, How, for Whom?” Washington DC, CGAP. from elsewhere. In- stead, countries in this region—four of which are least developed countries (LDCs)—can provide leadership and example through experimenting with new models and ways of doing things such that they do not erode past achievements but instead create more development opportunities. This paper therefore addresses issues affecting mobile money in the EAC, where cell phones transfer more than half a billion dollars monthly. The number of mobile phone users has long exceeded the number of people with bank accounts across the EAC. The purpose is therefore to demonstrate the need for the EAC to address issues relating to telecommunications and financial regulation to ensure that mobile money services bring the desired broad benefits, especially to the poor in the EAC. In doing so, the paper provides an analysis and comparison between the different platforms currently on offer in the various Member States. The paper analyses the legislative and regulatory environment in which mobile money is operating and how it has shaped the emerging models and services. Attention is given to the different regulatory frameworks in which the respective systems operate. Based on this analysis, the paper draws lessons and makes recommendations in terms of legislative and regulatory frameworks geared towards the increasing adoption and use of mobile money. 1.2. Principal research question: The paper seeks to answer the following question: What are the effective legislative and regulatory responses to mobile banking services in the East African Community (EAC)? 1.3. Aims and objectives of the research: This paper primarily addresses the principle question herein above. All the EAC Member States have active mobile-payment and mobile-banking initiatives currently underway; but, as least developed and low income Member States, they come from different starting points and face different issues. The aim of this paper is to provide a useful tool for regulators and mobile money providers in the EAC to engage more effectively. It elaborates commonly held positions in the mobile industry on some key policy and regulatory issues, backed up by evidence 1. 4. Design/methodology/approach: The paper provides an overview of the current mobile money landscape in East Africa in addition to describing the status of the regulatory framework in each of the five EAC Member States. It therefore entails analysis of EAC Member State national laws, regulations, bills and policy papers relating to ICT sector in order to establish how they address a range of challenges and issues brought about by the introduction of mobile money services. 1.5. Synopsis: The paper is organized as follows: Part I gives an overview of mobile money landscape across EAC. This part includes an overview of the different mobile money services along with the salient features of the services currently on offer across EAC and identifies some usability issues. Part II analyses the legislative and regulatory frameworks relevant to the mobile money service. Part III draws on lessons and recommendations across EAC to make enabling legislative and regulatory frameworks to help direct the development of mobile money in a way that is inclusive and that also favours mobile money use across the EAC. 2. MOBILE MONEY LANDSCAPE ACROSS THE EAC 2.1. Mobile money players In the EAC, the players involved in the Mobile Money include the following:8 (a) An MNO that provides the mobile infrastructure and customer base that is already using its communication services. MNOs ensure compliance with telecommunication regulations and policy within the country. (b) A bank or other financial institution with banking license and infrastructure that enables the exchange of money between different parties. Banks ensure oversight and regulatory compliance with national financial regulations and policy. (c) Regulatory institutions across different sectors. The key regulators in EAC include Central banks for the financial sector and ICT regulators for the communications sector. 8 Jenkins, B. (2008). “Developing Mobile Money Ecosystems.” Washington, DC: IFC and the Harvard Kennedy School. (d) An agent network that facilitates cash-in and cash-out to afford convertibility between mobile money and cash. Agents earn commission on various transactions carried out by mobile money users. (e) Merchants and retailers: they accept mobile money payments in exchange for different products and services. They help increase demand for mobile money by offering more avenues through which users can spend their mobile money. In return, they can minimise the need to handle cash. These include businesses that utilize mobile money as a means to deliver their services. (f) MNO’s subscribers: Users derive benefits by getting cheaper and more efficient means of transferring or paying money to other people or businesses within the network. 2.2. Types of mobile money transactions Mobile money services can be broadly categorized into three groups: (a) Mobile transfers: these are services entailing the transfer of mobile money from one user to another. Domestic mobile-transfers still dominate amongst the mobile money services across EAC. The bulk of these transactions occur between urban and rural areas, as migrants to urban areas send money back to the rural areas to support their extended families. In this case, mobile money replaces traditional informal methods like sending money with someone or by bus or taxi. Part of the success of mobile money is attributed to the lack of scale and reliability of informal methods.9 (b) Mobile payments: they are services where money is exchanged between two users with an accompanying exchange of goods or services. From mobile-transfers, MNOs have broadened mobile money services to include a range of mobile-payments. MNOs started out by targeting entities that receive recurrent payments from diverse customers like utility companies (e.g. power, water, sewage, Pay TV, etc.) and those that make bulk payments (e.g. salaries and school fees). Many of these services were launched as free promotional offers to help build the business-case and prove their utility to the consumer. For example, Safaricom clearly indicates that it is free to pay your bill with M-PESA at the moment. Kindly note that this is an introductory offer valid only for a limited period.10 Some service providers have stated that they can bear the cost for their customers remitting dues via mobile money because it affords them a cheaper avenue to collect dues from customers on a regular basis. Others, like the National Water and 9 Jack, William and Tavneet Suri, (2011). “Mobile Money: The Economics of M-PESA.” NBER Working Paper Series, No.16721, www.nber.org/papers/w16721 10 http://safaricom.co.ke/index.php?id=264 Sewerage Company in Uganda, have scrapped all of their cash collection centres and resorted to using banks and mobile money as the only ways for users to pay their dues.11 MNOs have also started cultivating merchants for mobile-payments, mainly targeting large entities with multiple outlets like supermarkets. For example, M-PESA is working with the various supermarket chains in Kenya and MTN Mobile Money is working with retail supermarkets in Uganda. To date, the biggest mobile-payment beneficiaries are the MNOs themselves through the sale of airtime or credit directly to consumers. This avenue to sell airtime is helping them to make significant savings through bypassing the traditional distribution system of scratch cards. MNOs save by avoiding the need to print new cards and pay commission to dealers and their agents.12 (c) Mobile financial services: they are services where mobile money may be linked to a bank account to provide the user with a whole range of transactions (savings, credits) that they would ordinarily access at a bank branch. Mobile money users are now able to withdraw money from some ATMs instead of visiting a mobile money agent. However, this approach only works in urban settings where ATMs are common. In addition, some banks have teamed up with MNOs to offer integrated mobile-financial service products like Iko Pesa13 (Orange and Equity Bank) and M-Kesho14 (Safaricom and Equity Bank) in Kenya. With M-Kesho, the M-PESA account on the mobile phone (which contains the mobile money) is linked to an Equity bank account, allowing the user to move money between the two accounts. As a result, M-Kesho has an additional layer that results in higher transactional costs when a user is cashing-out money across the two accounts. Conversely, Iko-Pesa is an actual Equity bank account directly accessible via a menu on the SIM, providing all the features that come along with a bank account plus the added benefit of a mobile phone access channel.15 Mobile- finance services are also being used by insurance institutions to leverage mobile money as a vehicle for cost reduction and improved efficiency in providing their conventional services. Some micro-finance institutions (MFIs) are using mobile money as a lower cost and safer way to disburse loans and collect payments. Micro-insurance institutions are similarly beginning to use mobile money to collect premiums and pay reimbursements to their customers. Financial institutions that receive mobile money 11 http://www.nwsc.co.ug/index03.php?id=69 Kabir Kumar & Toru Mino (2011). “Five business case insights http://technology.cgap.org/2011/04/14/five-business-case-insights-on-mobile-money 13 money.orange.co.ke 14 safaricom.co.ke/index.php?id=263 15 www.equitybank.co.ke 12 on mobile money,” deposits could potentially generate more revenue through retention of such deposits. Examples of MFIs using mobile money in Kenya include Faulu 16 , Kenya Woman’s Finance Trust (KWFT)17, Kenya Agency for Development of Enterprise and Technology (KADET)18 and Musoni.19 Tujijenge in The United Republic of Tanzania20 and Finance Trust21 in Uganda are other major MFIs using mobile money networks. Currently, mobile money transactions can be local (within the jurisdiction of one country) or international (across different national borders). International money transfers by Western Union in partnership with M-PESA are an example of the latter.22 From the foregoing, mobile money transaction in the EAC has provided a platform for innovation that can be leveraged by different third parties to provide useful services for small enterprises. From access to capital or credit through micro-finance to hedging risks with micro-insurance, from more efficient logistics to better inventory management and from better book-keeping methods to easier customer relationships management. The opportunities are boundless. 3. LEGISLATIVE AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS Mobile money transactions have presented regulatory challenges that could potentially hinder maximum development benefits. This is because firstly, mobile money blurs the traditionally distinct and independent sectors of regulation (most notably, the telecommunications and financial banking sectors). It often involves an overlap between multiple ministries and Government agencies, thus adding to the complexity of oversight needed. Secondly, due to the rapid growth in technological advancement, MNOs and other stakeholders are exploring emerging business opportunities like mobile banking. This in effect is changing the traditional business models and the financial landscape. Thirdly, there is limited legislative and regulatory experience in other countries and regions to draw lessons from when drafting relevant legislation and regulations. As is the case in most other developing regions, national regulations have not kept pace with developments in the field. It is therefore imperative that regional 16 www.faulukenya.com www.kwft.org 18 www.kadet.co.ke 19 www.musoni.eu 20 www.tujijengeafrika.org 21 www.financetrust.co.ug 22 http://safaricom.co.ke/index.php?id=254 17 and national authorities identify and address the gaps and potential overlaps between their existing legislative and regulatory frameworks. This part analyses the relevant EAC mobile money legislation and regulation. It first gives an overview of the different legislative and regulatory areas that impact mobile money. Secondly, it discusses selected issues that arise in mobile money operations within EAC. This analysis strives to identify crucial areas that offer a starting point for further analysis as national and regional regulators progress in developing the mobile money legislative and regulatory frameworks in EAC. 3.1 Overview of the legislative and regulatory areas of relevance to Mobile Money: Currently, there doesn’t exist any legislative or regulatory framework relevant to mobile money at the EAC level. It is therefore left to the Member States. The following is a brief overview of the various financial and ICT legislation and regulation relevant to the mobile money from the various Member States: KENYA: Some of the pertinent legislation that influences the operations of Mobile Money within Kenya includes: (a) Central Bank of Kenya Act (enacted 1966, amended through 2009)23—it creates the Central Bank of Kenya and defines its mandate. (b) Banking Act (enacted 1991, amended through 2010)24—it regulates the activities of banking institutions within the financial sector in Kenya. (e) Guidelines on Agent Banking (2010)25—provides for the appointment of agents to extend banking services within Kenya. (f) Draft Electronic Retail Transfers Regulation and Draft E-Money Regulation (stake holder consultations were organised and comments to the draft are now being integrated)26—regulate electronic money issuance and exchange, as well as its transfer between different parties within Kenya. 23 www.kenyalaw.org/Downloads/Acts/Banking%20Act.pdf www.centralbank.go.ke/downloads/acts_regulations/BankingAct_jan2011.pdf 25 www.centralbank.go.ke/downloads/bsd/GUIDELINE%20ON%20AGENT%20BANKING-CBK%20PG%2015.pdf 26 www.centralbank.go.ke/downloads/nps/Electronic%20%20Retail%20and%20E-regulations.pdf 24 (g) The Kenya Information and Communications Act (1998) as later amended in 2010— provide the mandate of CCK and a framework to regulate the information, communications, media and broadcasting subsectors. (h) A range of Kenyan information and communications regulations made by the Minister in charge of Information and Communications in tandem with the CCK to regulate various aspects of the communications sector that include consumer protection, competition, tariffs, numbering, interconnection, quality of service etc.27 (i) The Kenyan Competitions Act (2009) 28— has some elements of consumer protection and provides for the creation of an autonomous Competition Authority to replace the Monopolies and Prices Commission. UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA: Some of the pertinent legislation that influences the operations of Mobile Money within Tanzania includes: (a) The Bank of Tanzania Act (BoT) (enacted 2006)29 creates the Bank of Tanzania and defines its principal functions. (b) The Banking and Financial Institutions Act (enacted 2006) 30 –provides the legal framework for undertaking licensed banking operations within the United Republic of Tanzania. (c) There are a number of guidelines from BoT that are relevant to mobile money including the National Payment Systems Guidelines for retail payments, Rules and Regulations for Retail payments and the Guidelines for introducing electronic payments.31 (d) The United Republic of Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) Act no. 12 (2003) that established and provides the mandate of the communications regulator.32 27 http://www.cck.go.ke/regulations/sector_regulations.html www.kenyalaw.org/Downloads/Bills/2009/200903.pdf 29 www.bot-tz.org/AboutBOT/BOTAct2006.pdf 30 www.bot-tz.org/BankingSupervision/BAFIA2006.pdf 31 www.bot-tz.org/PaymentSystem/publications.asp 32 TCRA Act, www.tcra.go.tz/policy/Tanzania%20Communications%20Regulatory%20Act-2003.pdf 28 (e) The Fair Competition Act (2003) is meant to foster competition in different sectors, while at the same time protecting consumers. As part of the Act, the Tanzanian Government has set up the Fair Competition Commission (FCC)—to administer the law and the Fair Competition Tribunal (FCT)—to provide a judicial forum where appeals of UGANDA: Some of the pertinent legislation that influences the operations of Mobile Money within Uganda includes: (a) The Bank of Uganda Act (enacted 1969, amended through 2000) — created the Bank of Uganda, the financial regulator and defines its mandate. (b) The Financial Institutions Act (enacted 2004)33—provide the regulatory framework for the financial sector in Uganda. (c) Financial Institutions Licensing Regulations34 and other related regulations (enacted 2005)35—that guide the licensing and operation of financial institutions within Uganda. (d) The Uganda Communications Act (1997) 36— provides a legal framework for the communications sector in Uganda. It established the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC), the sector regulator and defines their mandate. RWANDA: Some of the pertinent legislation that influences the operations of mobile money within Rwanda includes: (a) Law no. 55 (enacted November, 2007)37—governs the mandate of the National Bank of Rwanda (BNR), the Central Bank that oversees the financial sector in Rwanda. 33 www.bou.or.ug/export/sites/default/bou/bou-downloads/ acts/supervision_acts_regulations/FI_Act/FIAct2004.pdf 34 www.bou.or.ug/export/sites/default/bou/bou-downloads/acts/supervision_acts_regulations/FI_Regulations/FI_ LicenseRegulations2005.pdf 35 www.bou.or.ug/export/sites/default/bou/bou-downloads/acts/supervision_acts_regulations/FI_Regulations/FI_ OwnershipControlRegulatns2005.pdf 36 http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/treg/Legislation/Uganda/Billamend27.pdf 37 www.bnr.rw/docs/publicnotices/Law%2055-2007.pdf (b) Regulation no. 04 (enacted April, 2011)38—defines a minimum set of requirements that banks in Rwanda need to meet to ensure effective business continuity practices.39 (c) Rwanda is working on a multi-sectoral competition and consumer protection law that is currently in draft form and before parliament. The new law is being prepared under the auspices of the Ministry of Trade and Industry 40 and will repeal older regulation that is currently used to enforce competition policy across different sectors like Law no. 41/63 (enacted February, 1950). It will also provide coherent consumer protection mechanisms that span different sectors as opposed to the sector-led efforts under the auspices of different regulators. BURUNDI: Some of the pertinent legislation that influences the operations of mobile money within Burundi includes: (a) The Multi-Sectoral Competition Law, Law no. 1 /06 (enacted March, 2010: It relates to issues of competition within Burundi. The regulation stipulates the appointment of a Competitions Commission that has not yet been put in place.41 (b) The Bank of the Republic of Burundi (BRB),42 the central bank has a number of statues that define its mandate and guide its activities. (c) The Banking Act, Law no. 1/017 (enacted October, 2003) that relates to the regulation of banks and financial institutions within the financial sector in Burundi. From the foregoing, it is evident that despite the colossal sums of money involved in mobile money transactions, there is currently no legal framework governing these transactions. Any kind of regulation falls back to the distinct sector specific regulation of ICT and financial sectors. The mobile network operators have no obligation to report or disclose information on mobile money services to the Member States central banks as the financial regulator or to the Communications Commissions as the telecommunications regulator. 38 www.bnr.rw/docs/publicnotices/Regulation%20No%20%2004%202011%20on%20Business%20Continuity%20%20 Management.pdf 39 www.bcr.co.rw 40 Rwanda’s Ministry of Trade and Industry website, www.minicom.gov.rw 41 www.iflr1000.com/LegislationGuide/373/Let-thecompetition-begin.html 42 www.brb-bi.net 3.2 Analysis of the legislative and regulatory issues to Mobile banking in the EAC: From the above section, it is evident that mobile banking has blurred the traditional distinct financial and ICT legislative and regulatory frameworks. This is because this new service has partitioned conventional financial services into a number of complementary functions:43 They include: Exchange between different forms of money (cash and mobile money in this case); Storage of money for safe-keeping; Transfer of money between different parties; Investment of the resulting net balance between deposits and withdrawals. Overlapping issues Mobile-banking sits at the intersection of a number of important policy issues. Each issue is complex in its own right, and is often associated with a different regulatory domain: as many as four regulators (bank supervisor, payment regulator, telecommunication regulator, and competition regulator) may be involved in crafting policy and regulations which affect this sector. The complex overlap of issues creates the very real risk of coordination failure across regulators. This failure may be one of the biggest impediments to the growth of mobilebanking, at least of the transformational sort. However, even without the additional complexity introduced by mobile-banking, many of these issues require coordinated attention anyway in order to expand access. It is possible; however, that mobilebanking may be useful because the prospect of leapfrogging may help to galvanize the energy required among policy makers for the necessary coordination to happen. The following are specialised regulatory areas and specific concerns that have potential to impact on mobile money markets and transactions. They are analysed here below: (a). Telecommunications Generally, ICT legislation and regulation cover radio and television broadcasting, as well as the more distinct forms of communication through fixed line telephony, mobile telephony, and the Internet. ICT users have an interest in fair network access and transparent disclosure of costs and fees. Regulators and industry endeavour to maintain an efficient system that serves the public needs while still allowing for economic growth. EAC mobile banking 43 Dittus, Peter and Klein, Michael. (2011) “On Harnessing the Potential of Financial Inclusion.” BIS Working Paper No. 347, Settlements, Bank for International | Klein, Michael and Mayer, Colin. (2011) “Mobile Banking and Financial Inclusion: The Regulatory Lessons.” Working Paper No. 166, Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. transactions are conducted through mobile telephony and associated networks, and are therefore affected by the governing ICT legislative and regulatory frameworks. There are currently no regional ICT legislation and regulations in EAC. However, national ICT authorities are operational in all EAC countries. International guidelines on ICT services do exist, and could serve as useful points as EAC further develops legislative and regulatory frameworks in the mobile money and ICT sectors. For example, the World Trade Organization, of which all EAC countries are Members, has served as a development forum for the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) Annex on Telecommunications,44 as well as the 1998 WTO Telecommunication Services Reference Paper (Reference Paper). 45 The Annex and Reference Paper both identify important aspects of telecommunications regulation that are worth considering in relation to mobile banking. These include transparency in licensing procedures, interoperability/ interconnection between telecommunication networks, resource allocation (e.g., with regard to frequencies, numbers, and rights of way), and competitive safeguards. Another important concept identified in the Annex is the need for technical cooperation at international, regional, and sub-regional levels. The issue of interoperability in relation to ICT networks is highly relevant in the context of mobile money. Mobile money platforms are still walled garden, customers can only exchange mobile money within a particular network. Currently, none of the mobile money platforms within EAC interface or directly work with another platform. For example, a user of MTN Uganda’s Mobile Money cannot send money that directly ends up in the mobile money wallet of an Airtel Uganda user. (b). Competition law Generally, the objective of competition law is to preserve and promote free market competition and consumer welfare protection in regulated industries. In order to achieve these objectives, competition law generally prohibits anticompetitive practices and the abuse of dominance by monopolistic businesses such practices include; predatory pricing, price discrimination and bundling. Competition law also has an impact on mergers and acquisitions, as well as unreasonable restraints on competition. In the EAC, national competition laws generally do not extend beyond Member State borders. With regard to mobile money markets, competition laws are relevant to the service costs to consumers, as well as allowable business practices and market 44 45 Full text available at: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/12-tel_e.htm Full text available at: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/telecom_e/tel23_e.htm structures under which mobile money operators must function.46 At the EAC level, the East African Legislative Assembly (EALA) has enacted an EAC Competition Act (2006), with provisions for a regional EAC Competition Authority. Generally, however, competition regulation in certain sectors is handled by sector specific regulators, either solely or with shared jurisdiction with competition agencies. Depending on each case, the move is towards signing of memorandums of understanding (MoUs) between the regulators in order to avoid possible conflicts. Currently, the ICT regulators handle interconnection issues among ICT service providers while the central banks deal with financial service providers. Historically in the EAC, access to participate in the ICT sector has been restricted to a few players with an aim of creating a viable market that can attract the necessary investment. This is not usually the case in the financial sector. So, the number of licenses issued by the ICT regulator compared to the central banks in any EAC Member State is typically much smaller. For example, in Uganda, there were only 6 licensed MNOs, but as many as 23 licensed commercial banks at the end of March 2011. 47 Thus, the perception of competition in the two sectors is different. While MNOs are working with partner banks, they are dominating mobile money within walled gardens at the moment and it is not clear how regulators across the two sectors will respond to competition issues given the convergence between their sectors fostered by mobile money. In addition, competition regulators are a relatively new phenomenon in the EAC. Even where competition regulators are in place, they still need to develop the capacity to monitor, investigate, control and prevent uncompetitive conduct, while determining how best to work with existing regulators in other pertinent sectors. Within EAC, Kenya has the oldest Competition Law, known as the Restrictive Trade Practices, Monopolies and Price Control (RTPMPC) Act Chapter 504 Laws of Kenya, dated 1988. It was revised in 2011 as the Competition Act 2009. The new law covers promotion of competition, consumer protection, establishes an independent competition authority and a competition tribunal to enforce it. The Competition Act 2009 was made operational though Kenya Gazette Supplement Notice No. 59, Legal Notice No. 73 on 1 August 2011. 48 The United Republic of Tanzania also has a 46 This is of particular relevance in the ICT/ mobile phone industry, as competition has not historically been an assured feature of this market. 47 See http://www.bou.or.ug/export/sites/default/bou/boudownloads/financial_institutions/2011/COMMERCIAL_ BANKS_IN_UGANDA_as_at_31_Mar_2011.pdf 48 See http://www.cak.go.ke competition law in place: the Fair Trading Act, 2003.49 Burundi enacted a process of establishing the responsible institution,50 while Rwanda and Uganda are at different stages of enacting their own competition regulations. (c) Lack of Legislative and regulatory harmonization It should be noted that the EAC strongly encourages regulatory harmonization, as is shown by Articles 126 and 47 of the Common Market Protocol, which call for the harmonization of national legal frameworks.51 However, in most sectors including the ICT sector, the current regulations in the EAC are still somewhat fragmented across different regulatory areas in the various Member States. As the EAC Partners continue to advance towards regional harmonization, it is important to bear in mind that the EAC strongly supports the sovereignty of its Partner countries. Thus, the EAC countries should emphasize collaborative efforts and information sharing whereby the EAC as a whole can develop in line with intra-regional best practices. Harmonization of regulatory frameworks can touch upon all aspects of regulation, and is therefore an important concept to bear in mind as various issues are explored. (d) Convergence of ICT and financial sectors As mobile money markets evolve, the previously distinct regulatory sectors of telecommunications and finance will continue to intersect, thus changing the regulatory landscape and potentially raising new issues for regulators to address. For example, jurisdictional and dispute resolution questions may arise. When mobile money disputes arise either on a consumer or industry level, which sector and corresponding regulatory agency will have jurisdiction over the claim or dispute, and how will dispute resolution procedures be determined? Additionally, as mobile money services extend across borders, national jurisdictional issues may also arise. 49 See http://www.competition.or.tz and Tribunal The United Republic of Tanzania’s Fair Competitions Tribunal website, http://www.fct.or.tz 50 See Law No. 1/06 of 25 March 2010 regarding the Legal Regime on Competition (Burundi Official Gazette, No. 3 bis/2010, p. 873. www.iflr1000.com/LegislationGuide/373/Let-the-competition-begin.html. 51 See for example: EAC legal framework for Cyber laws is a good example of such a progressive step. 4. ENABLING ENVIRONMENT FOR MOBILE-BANKING GROWTH IN THE EAC An enabling environment is defined in this paper as a set of conditions which promote a sustainable trajectory of market development in such a way as to promote socially desirable outcomes. These conditions are forged by larger macro-political and economic forces, as well as sector specific policy and laws. However, this paper focuses on the latter category as being within the power of policy makers and regulators to control and influence. To unleash the potential of mobile money, regulators must create an open and level playing field that allows both banks and non-bank providers to offer mobile money services – particularly MNOs, which are well suited to building sustainable services and extending the reach of the formal financial sector rapidly and soundly. An enabling policy and regulatory framework creates an open and level playing field that fosters competition and innovation, leverages the value proposition of both banks and nonbank providers, attracts investments, and allows providers to focus on refining operations and promoting customer adoption. Unfortunately, ineffective and divergent policies and cumbersome regulatory barriers between Member States have had a negative effect on the development of mobile money and the expansion of financial inclusion in the EACs’ Mobile money markets. 4.1. Dimensions affecting mobile-banking development in the EAC Mobile money is still a new market in most Member States; the following two dimensions in particular are affecting the market development trajectory: 1. Openness: does the policy, legal and regulatory environment allow for (or better encourage) the entry of new providers and approaches? If not, there is little room for innovation to come to market. 2. Certainty: does the policy, legal and regulatory environment provide sufficient certainty that there will not be arbitrary changes in future which may prejudice the prospects of new entrants? If not, entrants (at least those with a longer term horizon) will be discouraged from incurring the cost and risk of entry. Ideally, therefore, an enabling environment is one which is sufficiently open and sufficiently certain; but in reality, there may well be trade-offs between these two dimensions. It is often the case for new markets that one or other dimension is neglected: for example, Burundi has few laws or regulations and with limited regulatory capacity may be very open to new developments, however, there is a high level of uncertainty, for example, as result of arbitrary action in vague areas of the law, there is still little market development. 4.2. Enabling principles for mobile-banking development in the EAC This part proposes some core principles which together may help to create an enabling policy and regulatory environment for mobile-banking in the EAC. These principles define further the basic components which provide sufficient openness and certainty for the long term development of mobile-banking. The following are the proposed principles: (I) Policy makers, regulators and service providers should engage in inter-operability Regulators, service providers and policy makers should work together to understand different types of interoperability, including the benefits, costs, and risks. The role of the policy maker is to facilitate dialogue between providers and regulators, ensuring that interoperability brings value to the customer, makes commercial sense, is set up at the right time, and regulatory risks are identified and mitigated. Both customers and mobile money providers could benefit from the interoperability of mobile money services. The issue is when and how interoperability makes commercial sense for providers and creates value for customers. A collaborative approach to building interconnected mobile money environments Building an effective interoperable environment is going to require service providers to engage with policy makers and regulators. The policy maker should act as a facilitator, helping providers to create the road map that they will be primarily responsible for designing and implementing. The policy maker can also assist providers with their evaluation to ensure a) that interoperability is set up at the right time, b) that it creates value for both customers and providers, and c) that regulatory risks are identified and mitigated. Factors to be considered: Setting up interoperability at the right time52 the benefits of interoperability are more likely to emerge from mature mobile money deployments, such as ones with a functioning agent / third party network and an active customer base. For example in case of Kenya’s Safaricom which has agreements with Western Union and several banks53 Providers and customer value: Interoperability makes sense when more customers can be reached and when a greater frequency and variety of transactions can be performed. The majority of mobile money transactions are sent and received by customers within their own deployment, but allowing mobile money to flow between multiple deployments would likely increase the number and frequency of transactions across 52 See Gunnar Camner (2012), “Expanding the Ecosystem of Mobile Money: Considerations for Interoperability,” GSMA Mobile Money for the Unbanked position paper, London, UK. Available at http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/2012_MMU_ Expanding-theecosystem-ofmobile-money.pdf. 53 M-PESA is connected to 100 financial institutions, and including bill partners and everything the number of connections goes up to 500. networks, as well as the addressable customer base for each deployment. It would also make it easier for third parties to leverage mobile money and grow the network of companies and organizations that offer mobile money services. Service providers in the EAC face several challenges, however, including technical solutions, commercial agreements, and operational procedures. The costs associated with these integrations must be outweighed by the commercial benefits of performing more transactions. Regulatory risks: Depending on the business model that is permitted and adopted, mobile money providers could leverage three existing assets to implement interoperable mobile money systems:54 The mobile money platform (platform level): This allows mobile money to be transferred across mobile money deployments “wallet-to-wallet” and could include connections to switches, financial institutions, and companies. - The distribution network (distribution level): This allows transactions to be conducted across multiple distribution networks, or electronic retail payments acceptance schemes. - The SIM card (customer level): This allows a customer of one MNO to use the mobile money services of any other MNO, bank, or third party. At each of these levels, interoperability poses different costs and regulatory risks, and requires providers to enter contractual agreements that specify both joint and individual responsibilities, e.g., the responsibility to ensure minimum know your customer (KYC) requirements are met and monitored at the distribution level. Providers also need to come to an agreement on how to split revenues and costs, on customer fees (both the cost and the methodology), the disclosure policies, and the recourse system available to customers. - Given the sophistication of such efforts, the providers should be mindful of implementing one solution over another. The policy maker and the regulator could help providers to assess the particular risks and costs of interoperability at the platform, distribution, and customer level. The policy maker could also help to ensure that interoperability is not removing healthy competition that drives financial inclusion (e.g. investments in distribution if third party sharing is implemented in an immature market). (II) Mandating interoperability Some of the financial regulators have been tempted to require providers to become interoperable. From the perspective of policy makers, the motivation to mandate interoperability seems to be to: 54 See CGAP (2011), “Interoperability and Related Issues in Branchless Banking,” Power point presentation. Available at http://www.slideshare.net/CGAP/interoperability-and-relatedissuesin-branchless-banking-aframework-december-2011. - lower the costs of financial services - increase customer choice - increase competition and break dominant positions. It is difficult to predict for certain whether interoperability would actually lower costs and expand customer choice – the mobile money industry is still too new. In terms of increasing competition, it is the regulator’s responsibility to ensure that any intervention aimed at breaking a monopoly or abusive dominant position does not harm the industry, create an unequal playing field for current market players, or negatively impact customers. Competition authorities usually weigh the costs and benefits of these interventions carefully. In fact, high market share does not necessarily mean that consumers are paying excessive prices, that competition and product innovation are being stifled, or that the company with high market share is abusing its power (such as through exclusionary practices). The timing and cost-effectiveness of any regulatory intervention must be appraised carefully, and market-led solutions should always be the preferred option.55 This means that mobile-payment platform established by a mobile provider should be open to other account holders within agreed time; fair basis is established for new entrants to use existing payments infrastructure. Further that cell number portability should be required in a reasonable time frame. There is limited precedent to date of competition authorities applying general principles like these to the mobile payment environment in the EAC, although there are increasing cases of regulatory attention to potential anti-competitive practices in the payment sector, especially the card payment associations. (III) Cross-border interoperability at the EAC level There are other issues at the national level, including how to integrate a developed mobile money ecosystem into the national payments system. At a regional level, the issue of interoperability is also relevant as shown by the informal transfers happening across borders. An added complication is to deal with foreign exchange conversions if mobile money across borders is formalized in the EAC. As the EAC is at the forefront of the mobile money revolution, there are not many examples in existence to learn from. 55 This is a position often presented by expert policy makers and regulators. Among others, Carlos LopézMoctezuma, Chief Adviser to the President, Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores Mexico, and chair of AFI Mobile Financial Services Working Group) and Muhammad Ashraf Khan (Director of the Agricultural and Credit Department at the State Bank of Pakistan) during the session, “Breaking the Barriers of Mobile Financial Services to Make Financial Inclusion Real” at the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) 2012 Global Policy Forum (GPF) (see http://www.afi-global.org/news/2012/9/28/global-policyforum-2012-breaking-barriers); and Narda L. Sotomayor (Economist, Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFP of Peru) during the GSMA Mobile Money for the Unbanked (MMU) 2012 Leadership Forum (see http://www.gsma.com/mmu). Rather, countries in this region – four of which are least developed countries – face the challenge of charting a course by trying out new things in ways that do not erode current achievements and at the same time create maximum development opportunities. As a regional block aspiring to achieve more integration, the EAC Member States should continue their work towards adopting harmonized legislation on payments, including electronic and mobile payments. (IV) Collaboration between ICT and financial regulatory institutions. The need to collaborate between the two regulators— communications and financial—is becoming increasingly critical; while one is an expert at the financial aspects of mobile money, the other better understands the facilitating technology. Currently, individual contacts do exist amongst the two types of regulators in all the EAC Member states. As mobile money grows bigger and draws in more sectors, as it becomes an important channel for effecting payments and other types of financial services, new regulators will have to join the fold. 5. CONCLUSION Generally, the EAC Member States central banks are equipped to address risks present within retail payments systems in EAC, mobile money presents a new set of regulatory challenges. Mobile money involves players that traditionally have not fallen within the purview of central banks. Some of the issues that are of concern include whether MNOs should be directly licensed to issue mobile money; how the agents, which are critical for mobile money, should be regulated; Studies documenting risks across the mobile money chain have started to emerge.56 But they do recognise the nature, dynamism in the development of new business models as well as the uniqueness of various environments and how all of these do influence mobile money platforms in the EAC. EAC regulators have few other countries to turn to draw lessons. This further compounds the challenge of effectively regulating and protecting consumers, without stifling innovation. In the preceding part, a number of legislative and regulatory issues and potential policy actions have been discussed. The issues relate to interoperability as well as collaboration between regulators of all the relevant sectors both within and across the EAC. These issues are not exhaustive; they encompass common areas that need attention to help foster adoption and use of mobile money across the EAC. 56 Kenya School of Monetary Studies, USAID, Booz Allen Hamilton. (2010). “Mobile Financial Services Risk Matrix.” Washington, D.C.: USAID | Dittus, Peter and Klein, Michael. (2011) “On Harnessing the Potential of Financial Inclusion.” BIS Working Paper No. 347, Settlements, Bank for International | IFC Mobile Money Toolkit, Tool 10.10. Mobile Money Risk Scorecard at www.ifc.org/ifcext/gfm.nsf/Content/MobileMoneyToolkits2 The EAC’s aspiration is to and move towards integration, there is therefore an element of regulatory collaboration through EAC secretariat and other regional entities, like the East African Communications Organisation (EACO), which brings together the communications regulators. Through these bodies, regulators tend to look at issues from a regional perspective and strive to create compatible regulation to support both national and regional goals. While Central banks across EAC have worked on a number of regional projects like the Real Time Gross Settlements (RTGS) system, and others that are in the pipeline, mobile money is not yet on the table. Dialogue is largely happening at a national level with Kenya often leading the way owing to the success of M-PESA and the fact that they have somewhat longer experience than the other EAC countries.