Review Article - University of Toronto Medical Journal

advertisement

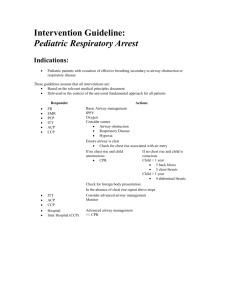

ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION FOR CONSIDERATION IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO MEDICAL JOURNAL Review Article Airway Foreign Bodies (AFBs) Ala’addin Mohammed Mubarak Salih Fifth year medical student, Faculty of Medicine, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan. Intern medical student, Pediatrics Emergency Center-Hamad General Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar. Correspondence Email: alaaddin.mohammed@yahoo.com 1 Airway Foreign Bodies (AFBs) Abstract: Airway foreign bodies (AFBs) form a very important issue mainly in fields of paediatrics and emergency medicine, due to its direct relation to the most important vital process, respiration. Moreover this topic is poorly covered in references, so this article tries to overcome this. Sudden entrance of an element into the airways is a widespread clinical scenario among children under 3 years. It leads to a broad spectrum of breathing abnormalities in respiratory rate and depth, ranging from partial to complete airway obstruction, depending on the size and site where the body lodges. On admission to the hospital, the main complaint is shortness of breathing (SOB). The diagnosis & subsequent approach nature depends on: proper history, physical examination findings, & ancillary radiographies. Management classically follows “Prevention is better than cure” through increasing public education and parents awareness in how to choose objects compatible with each age group and taking care of their children, however, if all these precautions fail and the intervention is deemed to be necessary, definitively it will be via bronchoscopic removal of the body. Again to say, the quicker the approach the lesser the complications. Keywords: Airway foreign bodies; respiratory tract; airway obstruction; Café Coronary; breathing difficulties. Definition: An airway foreign body (AFB) is an object that is abnormally present in the airway passages (i.e. mouth or nasal cavity, pharynx, trachea, principal or main bronchi, 2 terminal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles), most likely lodging in either a main or lobar bronchus1. The use of the term AFBs in this article refers to both aspirated (or inhaled) exogenous foreign bodies as well as bodies from endogenous sources. Table 1 summarizes the probable sites of occlusion and the subsequent complications. Table 1: Possible sites of airway obstruction and the main complication of each. Site of obstruction Mouth or nasal cavity Expected lung complication No effect due to alternative breathing by other opened entry route. Pharynx Naso-pharynx No effect due to alternative breathing by breathing by unobstructed oro-pharynx. Oro-pharynx No effect due to alternative unobstructed naso-pharynx. Laryngo- Complete collapse of both lungs. pharynx Trachea Complete collapse of both lungs. Main bronchi2 Complete collapse of one lung . Lobular bronchi Lobular lung collapse. Terminal bronchioles Partial lung collapse. Historical Background: Previously it was known as a “Café Coronary”, a term coined by Haugen in 19633. The first part of this description was given to it because it is usually happen in these 3 places, and regarding the second one is used to emphasis its high incidence in a compartment surrounding the heart which is the first part of the lower respiratory tract, the author could explain this depending on the fact that “coronary” is an adjective for anything associated with the heart, so this usage is seem to be logic because both the heart and upper part of the lower respiratory tract (i.e. the lower trachea, main bronchi, and bronchioles) are found in the inferior mediastinum 4. The first bronchoscopy for removal of a foreign body was done by Gustav Killian in 1897.5 Classification: There are several ways in which airway foreign bodies could be classified, here are the most important three. In classical classification17 they are differentiated according to patient age, foreign body category, and the body lodging site. According to the degree of foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO) there are two types: partial obstruction has a mild to moderate effect, and complete obstruction has a severe consequences. Regarding the foreign bodies origin they are of two sources: bodies of endogenous source like mucus masses (e.g. mucocoele)18 and bronchial casts (e.g. plastic bronchitis); bodies of exogenous source like solid particles (e.g. plastic bags, small items, ... etc), food particles (peanuts in about 40% of all cases 19, although it has been observed that there is a link between country and type of food aspirated; for example, while peanuts are commonly aspirated in the US and Europe, watermelon seeds, sunflower seeds, and pumpkin seeds are more prevalent in Egypt, Turkey, and Greece, respectively)20, and pills (tablets and capsules). Figure 2 shows this classification. 4 Classification of Airway Foreign Bodies According to degree Foreign Body Airway Obstruction (FBAO) Classical classification Patient age Foreign body type Foreign body location Partial obstruction Complete obstruction According to foreign body original source Endobodies Exobodies Figure 2: Classification of airway foreign bodies. Epidemiology: An American study suggests a mortality rate due to Foreign Body Airway Obstruction (FBAO) equalling 0.66 per 100,0006. Another detailed study summarizes AFBs prevalence as shown in Table 2.7 Table 2: Illustrates the incidence of AFBs among British boys and girls. > 0-1 yr > 1-2 yr > 2-3 yr > 3-4 yr > 4-5 yr > 5-6 yr > 6 yr Male 7.4 % 28.1 % 13 % 1.5 % 1.5 % 1.6 % 9.3 % Female 8.1 % 25.2 % 6.7 % 1.5 % 0.7 % 0.8 % 4.8 % In the UK, an old study found similar ratios for the age groups mentioned in the previous study with an expansion over elder ages, this shown in figure 1. 5 1% 8% 1% 4% 16% 0-1 yr. 2-5 yrs. 6-15 yrs. 27% Figure 1: Death incidence by inhaled foreign bodies 16-25 yrs. 43% 26-35 yrs. according to age in Britain 36-45 yrs. in 1954. 46-55 yrs. In Australia, the incidence of asphyxia secondarily attributed to FBAO is 15.1 per 100,0008. It has also been shown that FBAO cases are more common in males than in females by a ratio of 2:1 for unknown reasons9, the peak being in early childhood (children between the ages of six months and three years). It is also common in the elderly, especially during the sixth decade of life10 but it is less frequent in adults, in which it occurs only accidently11 (an interesting case report describes a 65-year old male who presents with a aspired screwdriver that had been lost by his dentist during tooth implantation)12 Also, it is more common in those who have mental retardation, those who have psychotic problems, and those who have attempted suicide many times13. Aetiology: Causes are of great variety, primarily due to engulfing something that is totally shouldn’t present in the mouth (e.g. toys, coins, ..... etc), or particularly if that 6 element doesn’t suits the patient age or mental abilities like peanuts for children under two years because they lake the necessary skills to masticate (chew) it properly. A second possible cause is the physical movement during eating which disrupts concentration and increases respiratory rate & depth leading the food into the respiratory passages. Thirdly, AFBs may occur due to misdirecting of solid food or liquid fluids into the airways rather than the gastrointestinal tract during the second stage of swallowing (deglutition), the pharyngeal stage14. Obstruction of the airway tracts originating from an endogenous source may result in case of mucoid impaction or bronchial casts formation characterizing plastic bronchitis15, its exact pathophysiology is unknown16 but it is commonly seen in chronic asthmatics, adults with cardiac & pericardial diseases, and children with congenital heart deformities. Pathophysiology: The nature of the foreign body determines the degree of immunological reactions. Metallic bodies cause very little immediate infection, while lipidic materials stimulate intense chemical inflammatory reactions in a response for its fatty acid content 21. Starchy food (e.g. cereals, legumes, ..... etc) has the character of adsorbing water 22 resulting in an initial partial obstruction that swells to end with complete one. Clinical Features: 1) Symptoms: Sudden onset of the symptoms is a must, so the patients come with a very acute history that may includes coughing & sneezing which consider as a “Protective Reflex” in order to stop further foreign body invasion. They both likely to be initiated with deep inspiration followed by forced expiration against a closed glottis, this will 7 increase intrapleural pressure markedly resulting in an explosive air outflow. Sneezing differs only in one point that during which the glottis is kept opened. 23 Choking24 occurs simply due to the mechanical obstruction, and leads to breathing difficulties combined by hoarse voice or dysphonia. Overall, AFBs cases present usually with anxiousness25 that may be associated with ptyalism26 as a result of sympathetic stimulation and psychiatric factors. 2) Signs: Clinical findings may include raspy respiration27, hypopnea, and dyspnea in association with signs of breathing difficulty like noisy breathing, nasal flaring, and usage of accessory respiratory muscles. Another sign is slightly declined respiratory rate, which acts in association with previous ones to decrease air entry usually unilaterally and subsequently develop hypoxia, hypercapnia, and cyanosis. On auscultation, we search for any wheezing sounds either bilaterally in case of partial upper respiratory tract obstruction, or unilaterally in case of obstructed lower respiratory tract indicating an ominous sign. Additionally, the examining doctor may hear what so termed sonorous rhonchi which is a special high pitched wheezing indicates aspiration of a large foreign body28. Finally, stridor sounds could be listened but with a special criteria categorizing it as an expiratory stridor indicating lower respiratory tract obstruction29. Differential Diagnoses: Many pulmonary diseases share the same symptoms and signs and should be considered, especially if the obtained history is not complete. These diseases could be divided according to the site of obstruction into:30 epiglottis obstructive diseases (e.g. epiglottitis and subglottic laryngitis)31, tracheal obstructive diseases (e.g. croup, 8 tracheal and paratracheal mass lesions, tracheomalacia, and tracheal stenosis), bronchial obstructive diseases (e.g. Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformation (CCAM), Bronchial compression, and plastic bronchitis also known as fibrinous, pseudomembranous, Hoffman’s, or cast bronchitis32), bronchioles obstructive diseases (e.g. bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans, and bronchiolitis Obliterans with Organizing Pneumonia (BOOP)), and lobar obstructive ones (e.g. asthma and lobar atelectasis). Diagnosis: Diagnosis requires the following ordered steps. Step one is the obtaining of a full history stressing firstly on whether there was any witness of the aspiration process, and secondly on the onset of the symptoms whether it appeared suddenly or developed gradually. The next step is conducting the physical examination mainly for E.N.T., eyes, and mucosa of the mouth and lips, in addition to the vital signs. The last step is targeting the diagnosis through the following test(s). These investigations are either radiographic or laboratory. Ordering in a priority declining manner, they are started by the Chest X-Rays (CXRs), investigating for mild or obvious hyperinflation signs present in the following views: - Anterio-posterior (AP) view or Inspiratory-expiratory film to estimate generally the volume of the two lungs and whether any one is hyperinflated or even collapsed due to partial or complete obstruction, respectively. A common mistake is taking the image during inspiration which shows no abnormalities, rather expiratory CXR films gives more information33. - If a complete obstruction is excluded, comparison of the right and left lateral decubitus views is mandatory, and hyperinflation of the lung contralateral to the 9 obstructed lung would be expected; this would not occur in a unilateral or even bilateral partial obstruction. Generally, Inspiratory-expiratory films occupies the first order of AFBs diagnostic techniques preceding the decubitus views which are a less preferable choice, because establishing and distinguishing the lung boundaries from a side view requires an expertise reader especially if the patient was a kid. Direct bronchoscopy for visualizing and removal of the trapped foreign bodies in anatomical dead spaces of the upper and upper-lower respiratory tracts could be done, bronchoscopy gives good results for smaller particles if applied early34. Other detectable tests of less use in this case are Computerized Topography (CT scan), and Iodine or Barium fluoroscopy35. Other investigations to estimate the patient general condition could be done like pulse oximetry and arterial blood gases saturation. Besides Complete Blood Count (CBC) and serum electrolytes. Reaching the definite diagnosis requires positive results in two diagnostic steps out of the three which are: a history of foreign body inhalation or mucocoele impaction, physical examination findings including one or more of the previously mentioned clinical signs, or positive results of the test(s). Management: Treatment is mainly preventive via increasing parents knowledge in how to take care of their kids, lead them to choose the toys that originally designed to suit the child’s age group, help them to select appropriate objects and avoid the small items, and finally advise them to keep close supervision. 10 In case of witnessed foreign body aspiration or sudden onset of AFB symptoms, parents should rapidly rush the patient to the hospital or call for ambulance help, during this they should apply the Basic Life Support (ABC) followed by the necessary first aid procedures. The most likelihood defence is the active coughing, the next lifesaver is Heimlich maneuver in case of complete obstruction. Artificial respiration mechanisms like Mouth-to-Mouth Breathing and Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) are absolutely contraindicated because they create high pressure gradient that may worsening the condition, instead, cautiously they could be applied if the trapped body was ultimately severe to maintain some degree of respiration36. In hospital emergency department, while the doctor diagnosing and evaluating the case he may prescribes oxygen therapy to overcome patient’s desaturation. Mechanical ventilation may used only if the patient was almost to die and there were no bronchoscopy-trained surgeon on-reach, these restrictive precautions based on what theoretically expected following mechanical ventilation of creation of an outer positive atmospheric pressure that may push the lodged body deeper. If there is a strong suspicion of foreign body aspiration of either endogenous or exogenous sources, the physician shouldn’t wait more and send the patient to the operation room as soon as possible, where if deemed necessary the surgeon initially applies rigid bronchoscopy, which is the first choice of management for its safety. The second choice is flexible fibre optic bronchoscopy37, which is rarely used for its high risks originating from its poor degree of both ventilation and controlling the trapped foreign body during the process. The last approach is through tracheostomy38 that used very rarely for removal of unusual foreign bodies that couldn’t brought out through rigid bronchoscopy, also it may be used in tandem with laryngoscopy for treatment of late laryngeal obstruction39. 11 Operations for removing AFBs are very safe, but in the few incidences during which the surgeon expects or has already faced some complications, he may prescribes some steroids or antibiotics as inflammatory prophylactic pre- or postoperative medications.40 Following discharge, parents and other family members should observe the patient closely. Complications: Early diagnosis and adequate management are essential to prevent pulmonary and cardiac complications, and ultimately to avoid radical lungectomy. Generally, complications depend on the nature of the foreign body e.g. sharp AFBs may lead to lung perforation. Anyway, a prolonged staying of the foreign body will lead to more retardation of the condition, that usually precedes other complications like asphyxia which is acutely developed hypoxia & hypercapnia that stimulate violent respiration and sharp rise in blood pressure and heart rate. Pulmonary oedema is another complication caused by chemical irritation of the alveolar epithelium, few hours later the patient develops cyanosis and shock status that ends as sepsis following secondary bacterial infection. Longstanding oedema with inflammatory exudates formation may complicated into aspiration pneumonia, and further more it may be changed into bronchiectasis or lung abscess that occludes the airways resulting in its dilation and scarring, the patients present with cough and purulent sputum41, emphysema or trachea-oesophageal fistula are the last stage of this complicating cascade caused by the inflammation. 12 Another and special type of infections appears as bronchial granuloma42, that commonly seen surrounding vegetable matters and distinguished microscopically by presence of foreign body giant cells43. Conclusion: AFBs is an evolving medical issue that will be of increasing importance, especially with an explosion in the birth rate in certain regions like Africa, Middle East, and Latin America44. Additionally, an increased pace of life today may affect both children’s awareness of objects entering their mouths and parents’ abilities to supervise their children. What is really important for parents is to target prevention, which is the cornerstone and root reason in AFBs avoidance. While for doctors if a case comes with signs similar to what have been mentioned, they should keep in mind AFBs as a priority in their differential diagnosis list. Acknowledgements: The author thanks Dr. Khalid M. A\Allah (Paediatric consultant) for his endless editing contributions. I would also like to thank Dr. Mohammed B. Al-Nayer (Paediatric senior specialist) for his guidance and support during the preparation of this article. Their continuous enthusiasm and encouragement are greatly appreciated. 13 References 1. Helen Williams. Inhaled foreign bodies. ADC Edu Pract Ed 2005; 90 (2): 31-3. 2. Wick R, Gilbert JD, & Byard RW . Café Coronary Syndrome ‘fatal choking on food’: an autopsy approach. J Clin Forensic Med 2006 Apr; 13 (3): 135-8. 3. Fleischer K Erkennung, & Entfernung Von. Bronchial-fremdkorpern-einst Jetzt. Ther Ggegenw 1974; 113: 348-58. 4. Chummy S Sinnatamby. Last’s Anatomy Regional and Applied. 11 th Ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. 5. Mittleman RE, & Wetli CV. The fatal cafe coronary; Foreign-body airway obstruction. JAMA 1982 Mar 5; 247 (9): 1285-8. 6. Hughes CA, Baroody FM, & Marsh BR. Pediatric tracheobronchial foreign bodies: historical review from the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996 Jul; 105 (7):555-61. 7. Mucoid impaction [homepage on the Internet]. Buckinghamshire: General Electric Company; 2010. Available from: http://www. medcyclopaedia.com/ 8. Cotton RT, Myer CM, Shott SR. The pediatric airway: An interdisciplinary approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 1995. 9. Rimell FL, Thome A Jr, Stool S, et al. Characteristics of objects that cause choking in children. JAMA 1998 Dec 13; 274 (22): 1763-6. 10. Rothmann BF, Boeckman CR. Foreign bodies in the larynx and tracheobronchial tree in children: A review of 225 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Sep-Oct 1980; 89 (5 Pt 1): 434-6. 11. Henry KK Tan, Karla Brown, Trevor McGill, Margaret A Kenna. Airway foreign bodies (FB): a 10-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000; 56: 91–9. 14 12. Choking and Foreign Body Airway Obstruction (FBAO) [homepage on the Internet]. London: EMIS; 2011. Available from: http://www. patient.co.uk/. 13. Farhad Baharloo, Francis Veyckemans, Charles Francis, Marie-Paule Biettlot, Daniel O. Rodenstein, Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies: Presentation and Management in Children and Adults. Chest 1999 May; 115 (5): 1357-62. 14. Review of Inhaled Foregin Body [homepage on the Internet]. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.; 24 Aug 2007. Available from: http://www.mdconsult.com/. 15. I Alfageme, N Reyes, & M Merino. Aspirated foreign body. Int J Pulmon Med 2007; 7 (1): 5-6. 16. Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc 1995 Jan; 41 (1): 39-51. 17. CLN Robinson, & William W Mushin. Inhaled foreign bodies. Br Med J 1956 Aug 11; 2: 324-8. 18. HA El-Munshid. Gastrointestinal Physiology. In: MY Sukkar, HA El-Munshid, MSM Ardawi. Concise Human Physiology. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2000, P. 159. 19. JY Park, AA Elshami, DS Kang, TH Jung. Plastic Bronchitis. Eur Respir J 1996; 9: 612-14. 20. D Vijayasekaran, A P Sambandam, N C Gowrishankar. Acute Plastic Bronchitis. Indian Paediatr 2004 Dec 17; 41: 1257-9. 21. William F Ganong. Review of Medical Physiology. 22th Ed. London: McGraw-Hill; 2005, P. 678. 22. Inhaled Foregin Body [homepage on the Internet]. Florida: DSHI Systems Inc.; 27 Apr 2009. Available from: http://www.freemd.com/. 15 23. Paulo FS, Bittencourt, Paulo AM Camargos. Foreign body aspiration. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2002; 78 (1): 9-18. 24. Robert A Harris. Carbohydrate Metabolism: Major Metabolic Pathways and their Control. In: Thomas M Devlin, Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. 50th Ed: New York; Wiley-Liss, 2002, P. 651. 25. Foregin Body Aspiration [homepage on the Internet]. Minnesota: Family practice notebook, LLC.; 22 Mar 2010. Available from: http://www.fpnotebook.com/. 26. Tarig Hakim Merghani. The Core of Medical Physiology. 1st Ed. Khartoum: Khartoum University Printing Press; 2008. 27. Singh B, Kantu M, Har-El G, Lucente FE. Complications associated with 327 foregin bodies of the pharynx, larynx, & esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997;106: 301-4. 28. Sapira JD, & Orient JM. Sapira's art & science of bedside diagnosis. Hagerstwon: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. 29. Joseph T Zerellaab, Michael Dimlerab, Leigh C McGillab, Kenneth J Pippus. Foreign body aspiration in children: Value of radiography and complications of bronchoscopy. J Pediatr Surg 1998 Nov; 33(11): 1651-4. 30. Robert C. Brasch. Airway Obstruction in Children: From Croup to BOOP [monograph on the Internet]. Berlin: Siemens and Bayer Schering Pharma; unknown date. Available from: http://www.star- program.com/resource.ashx/abstract/973 31. Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects & food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc, 1995; 41:33-8. 16 32. LJ Hoeve, J Rombout, & DJ Pot. Foreign body aspiration in children: The diagnostic value of signs, symptoms and pre-operative examination. Clin Otolaryngo & Allie Scien Feb 1993; 18 (1): 55-7. 33. DM Griffiths, NV Freeman. Expiratory Chest X-Ray Examination In The Diagnosis of Inhaled Foreign Bodies. Br Med J 1984 Apr; 288: 1074-5. 34. Foreign body aspiration-Diagnosis-Best Practice [homepage on the Internet]. London: BMJ Publishing group; 2010. Available from: http://www.bestpractice.bmj.com/. 35. Swanson KL. Airway foreign bodies: what’s new?. Semin Resp Crit Care Med 2004 Aug 25; 4: 405-11. 36. Arthur C Guyton, John E Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 11 th Ed. Pennsylvania: Elsevier Inc.; 2006, P. 155. 37. Sami El-Yas & Mohammed E. Ahmed, Surgical removal of perfume stopper impacted in the pharynx, KMJ 2008 May;1 (2): 93-4. 38. Andrew H Limper, & Udaya B Prakash. Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies in Adults. Ann Intern Med 1990 Apr 15; 112 (8): 604-9. 39. Foregin bodies, trachea [homepage on the Internet]. Virginia: Medscape; 8 Sep 2009. Available from: http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/. 40. O A Abdulmajid, A M Ebeid, M M Motaweh, I S Kleibo. Aspirated foreign bodies in the tracheobronchial tree: report of 250 cases. Thorax 1976; 31(6): 635-40. 41. Vinary Kumar, Abul K Abbas, Nelson Fausto, Richard N Mitchell. Robbins Basic Pathology. 8th Ed. Philadelphia: Sunders Elsevier; 2007. 42. Juerg Barbena, Robert G. Berkowitzb, Andrew Kempc, John Massie. Bronchial granuloma: where's the foreign body?. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngo 2000 Jul 14; 53 (3): 215-9. 17 43. RNM MacSween, K Whaley. Muir’s Textbook of Pathology. 13 th Ed. London: Arnold; 1992. 44. List of sovereign states and dependent territories by birth rate [homepage on the Internet]. Los Angeles: Wikipedia; http://en.wikipedia.org/. 18 19 Dec 2010. Available from: