Quick Diagnosis

advertisement

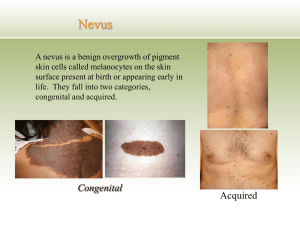

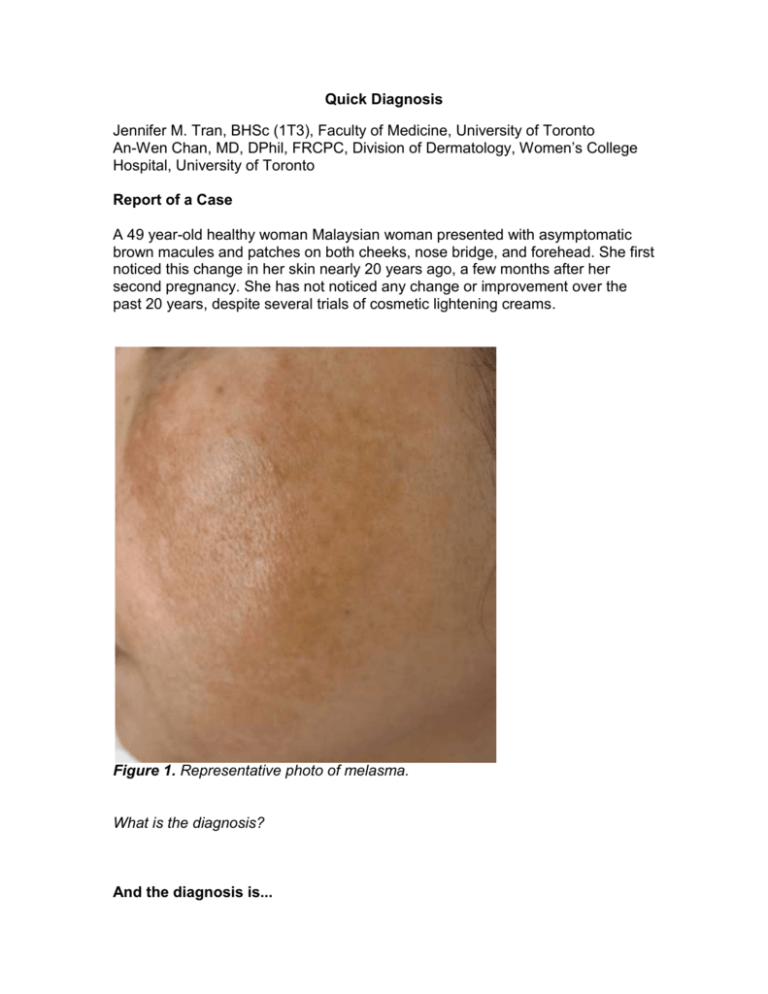

Quick Diagnosis Jennifer M. Tran, BHSc (1T3), Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto An-Wen Chan, MD, DPhil, FRCPC, Division of Dermatology, Women’s College Hospital, University of Toronto Report of a Case A 49 year-old healthy woman Malaysian woman presented with asymptomatic brown macules and patches on both cheeks, nose bridge, and forehead. She first noticed this change in her skin nearly 20 years ago, a few months after her second pregnancy. She has not noticed any change or improvement over the past 20 years, despite several trials of cosmetic lightening creams. Figure 1. Representative photo of melasma. What is the diagnosis? And the diagnosis is... Diagnosis: Melasma Hyperpigmentation is extremely common in pregnancy and occurs most often around the areola, abdomen (linea nigra), axilla, face, and medial thighs.1 One of the most common examples of pregnancy-associated hyperpigmentation is melasma (from the Greek word melas, meaning “black), also known as the “mask of pregnancy” or “chloasma” (from the Greek word chloazein, meaning “green”).2 Melasma is an acquired, symmetrical hyperpigmentation of sun-exposed areas of the body, most commonly occurring on the face. It is estimated that 5-6 million women in the United States alone are affected by the condition. Melasma affects mostly women (who account for over 90% of all cases), with Fitzpatrick skin types III, IV, V, or VI. Correspondingly, melasma is seen more commonly in people of Asian, Hispanic, and African-American descent.4 Melasma, though benign, can be extremely psychologically distressing and has been shown to have a significant impact on quality of life, social, and emotional wellbeing. 5 Etiology The exact cause and pathophysiology of melasma remains unknown, though certain risk factors have been identified. Pregnancy is a clear precipitant, as well as hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives.2 Although cessation of exogenous hormone use can cause remission of the condition, pregnancyassociated melasma can last for decades after pregnancy. Biopsies of melasmaaffected skin have shown increased estrogen receptors, further suggesting a role for hormonal influence in the development of the condition.6,7 Several studies have also suggested a genetic component, with an estimated 33% - 56% of patients reporting a positive family history.8,9,10 Sun exposure also plays a key role in both the development and prevention of the condition.2,10 Clinical Features Melasma tends to present as hyperpigmented macules and patches that range from light to dark brown, with occasional grey-tinge. Pigmentation may be guttate or confluent. Darker patches of skin gradually develop over weeks to months on sun-exposed areas of the face, particularly on the cheeks, forehead, and nose.2 Pathology Melasma can be divided into three main patterns based on the histopathological location of increased melanin: epidermal, dermal, and mixed (a combination of epidermal and dermal). Histological analysis of melasma biopsies have shown increased solar elastosis, melanocytes, melanophages, and melanin deposition. Melanocytes also seem to be more biologically active, exhibiting increased numbers of dendritic processes and organelles related to synthesis (Golgi apparatuses, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria).2,11-14 Diagnosis Melasma is diagnosed based on primarily on clinical history and examination. Wood’s lamp examination (UV light) may in some cases provide further detail about the histological subtype of melasma (epidermal, dermal, or mixed). Dermatoscopic examination can reveal an annular-granular pattern in melasma lesions, but does not often provide significant diagnostic utility in clinical practice given the characteristic history and physical exam findings that accompany most cases of melasma.15 Some mimickers of melasma include solar lentigines, acanthosis nigricans, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation, and frictional melanosis.2 With conscientious and thorough examination as described above, and a skin biopsy if necessary, melasma can usually be distinguished from these other dermatological problems.2 Treatment Melasma remains a common yet extremely difficult to treat condition. Sun protection is a key component of any treatment plan. In general, conventional treatments include sun protection, bleaching creams (e.g. hydroquinone), acne treatments (e.g. topical retinoids), and facial peels (e.g. glycolic acid peels). Triple-combination creams including hydroquinone, tretinoin, and steroids have also been used. A recent Cochrane review4 of 20 studies (n=2125 participants in total) reviewed 23 different topical and systemic treatments for melasma, and found the greatest improvement with triple-combination creams compared to hydroquinone alone (RR 1.58, 95% CI 1.26-1.97) or with dual combination creams of hydroquinone and tretinoin (RR 2.75, 95% CI 1.59 to 4.74), hydroquinone and fluocinolone acetonide (RR 10.50, 95% CI 3.85 to 28.60), and tretinoin and fluocinolone acetonide (RR 14.00, 95% CI 4.43 to 44.25). The adverse events most commonly reported were mild and temporary, including skin irritation, burning, and itching. Other treatment modalities that have been recently investigated include laser treatments such as Q-switched ruby laser, erbium:yttrium aluminum-garnet laser, carbon dioxide laser, intense pulsed light, and fractional resurfacing. These modalities have generally shown only modest and transient effect4,16 and often pose a significant risk of worsening the condition with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. More trails need to be conducted in order to further characterize the efficacy of such treatment modalities. Back to the case This patient was diagnosed with melasma (epidermal subtype) and reassured of the benign nature of her condition. We discussed the importance of ongoing sun protection, including wearing a sunscreen of at least SPF 30 and clothing barriers. As per the patient’s request, we also discussed cosmetic treatments including topical hydroquinone, triple-combination creams, and glycolic acid facial peels. The patient opted for a trial of hydroquinone cream and was scheduled to return in 8 weeks for follow-up. Conclusions - Melasma is a common and benign skin disorder characterized by symmetrical macules and patches of hyperpigmentation on the face - - It is associated with cosmetic disfigurement and significant psychological distress Though the pathophysiology of melasma is not yet fully understood, risk factors include pregnancy, exogenous hormone use, family history, darker skin type, and sun exposure Current treatments are variable in their efficacy and include sun protection, topical treatments, chemical peels, and laser treatment More research needs to be done to further elucidate the pathophysiology and potential treatments for this chronic and difficult to treat condition. References 1. Elling SV, Powell FC: Physiological changes in the skin during pregnancy. Clin Dermatol 1997,15(1):35-43. 2. Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: A comprehensive update (Part 1). J Amer Acad Dermatol 2011;65(4):689-97. 3. American Academy of Dermatology. Dermatologists Dis-’Patch’ Dark Side of Melasma.Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/newsreleases/dermatologists-dis-patch-dark-side-of-melasma-58900367.html (Accessed March 18, 2012). 4. Rajaratnam R, Halpern J, Salim A, Emmett C. Interventions for melasma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD003583. 5.Freitag FM, Cestari TF, Leopoldo LR, Paludo P, Boza JC. Effect of melasma on quality of life in a sample of women living in southern Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008;22:655-62. 6. Jang YH, Lee JY, Kang HY, Lee ES, Kim YC. Oestrogen and progesterone receptor expression in melasma: an immunohistochemical analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24(11):1312-6. 7. Lieberman R, Moy L. Estrogen receptor expression in melasma: results from facial skin of affected patients. J Drugs Dermatol 2008; 7(5):463-5. 8. Tamega AD, Miot LD, Bonfietti C, Gige TC, Marques ME, Miot HA. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; Epub ahead of print. 9. Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: a clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol 2011; 56(4):380-2. 10. Ortonne JP, Arellano I, Berneburg M, Cestari T, Chan H, Grimes P, Hexsel D, Im S, Lim J, Lui H, Pandya A, Picardo M, Rendon M, Taylor S, Van Der Veen JP, Westerhof W. A global survey of the role of ultraviolet radiation and hormonal influences in the development of melasma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009; 23(11):1254-62. 11. Grimes PE. Melasma: etiologic and therapeutic considerations Arch Dermatol 1995; 131:1453 12. Sanchez NP. Melasma: a clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 4:698. 13. Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, Kim J, Lee KB, Yim H, Sohn S, Im S. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:228-37. 14. Miot LD, Miot HA, Polettini J, Silva MG, Marques ME. Morphologic changes and the expression of alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone and melanocortin-1 receptor in melasma lesions: a comparative study. Am J Dermatopathol 2010; 32(7):676-82. 15. Stolz W, Schiffner R., Burgdorf W H C. 2002. Dermatoscopy for facial pigmented skin lesions. Clinics in Dermatology 20:276-278. 16. Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: A comprehensive update (Part 2). J Amer Acad Dermatol 2011;65(4):699-714.