Running head: REFLECTIVE INQUIRY A WAY OF KNOWING

advertisement

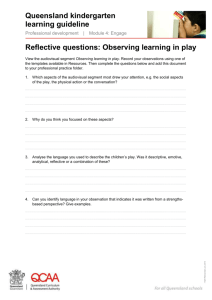

Running head: REFLECTIVE INQUIRY A WAY OF KNOWING Reflective Inquiry as a Way of Knowing Jerusalem Merkebu Ways of Knowing 800 May 08, 2012 Professor Stephen White 1 REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 2 Key Terms: Reflection, Introspection, and Inquiry Intertwined Due to the voluminous definitions of reflective inquiry the consensus among the literature, the specific definition that it’s a conscious, systematic, and disciplined introspective activity directed at enhancing professional practice, will be used for constructing it as a way of knowing here. Inherent in reflection is an inquiry disposition, that is, openness to discovery and exploration (Larrive & Cooper 2006). Introspection as defined by Merriam-Webster is “a reflective looking inward, an examination of one's own thoughts and feelings.” Historical Background From Introspection to Reflection The life of the human mind has been quite a fascination for decades. Great philosophers from Immanuel Kant to William Wundt, to more recently John Dewey, are just a few among the many who have sought to explicate what constitutes the elusive nature of mental life. Accordingly, Swindle (1999) articulates, “Beginning with Kant, the function of reflection was to determine how the mind conceives of itself as a subject related to itself and others” (p.19). Though appreciating the nature of “inner experience,” philosophers like Kant and Leibniz failed to see the significance of studying consciousness as a critical scientific activity (Danziger, 1980). Conversely, Fichte contended the importance of self-consciousness leading in the 1850s to Fortlage’s attempt to conduct empirical work in introspection. The history of introspection burgeoned greatly as 180 experimental studies were published on this construct between 1883 and 1903 (Danziger, 1980). Although philosophical debates against “systematic introspection” by other philosophers such as Lange and Comte sustained, still others were grappling between the fine lines of empirical and logical reflection (Swindal, 1999). Transcending the theories of consciousness to the next level, William Wundt distinguished “self-observation” and “internal REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 3 perception” as critical components of introspection that could be experimentally observed (Danziger, 1980). The ramifications of “free inner experimenting” brought forth a period of introspective analysis, from 1903 to 1913, by many philosophers like Lipps, Titchener and many more, who disseminated it to areas of memory, affect, and thinking (Danziger, 1980). Thinking, which is a consistent characteristic of reflection (Copeland et al., 1993), in particular will be of interest in exploring reflective inquiry as a way of knowing. Parallel to this line of inquiry, in 1910 John Dewey published How We Think, where he explored the idea of the trained power of thought and reflective introspection. For him the notion of thinking, which he viewed as anything occurring in the mind/head, was of not an incident of “spontaneous combustion,” rather the “consecutive ordering” of thoughts yield reflection (p.12). Dewey’s introduction to a disciplined mental habit that has the capacity to “turn things over,” which he contended was typically stimulated by perplexity, laid the foundations of reflective thinking (Dewey, 1933 p.66). He articulated this notion of a double movement in thinking, not seeking to corroborate or refute, and the capacity to suspend judgment; essentially the aptitude to go beyond mere de facto or the restrictions of the unconscious to conscious and deliberate effort (Dewey, 1933). Inspired by Dewey’s work and the desire to overcome the narrow model of technical rationality, which proves insufficient, for solving divergent dilemmas that commonly arise outside standard techniques or theories, Donald A. Schon, in The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, proposed reflection-in-action: consciously reflecting while working on a task and reflection-on-action: reflecting back on competed task (Schon,1983). Thus, he popularized what it meant to become a reflective practitioner and penetrated the works of some of the most influential thinkers of our time such as Argyris, Boud, Kolb, Gibbs, Senge REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 4 Mezirow, Hartman, Johns, Zeichner, Rolfe, Weick and countless more. Ultimately, this new orientation to reflective thinking nullified operating in a mode of advocacy and instead heavily promoted a stance of inquiry. Reflective Inquiry definition and discourse. The plethora of literature on reflective inquiry lucidly reveals there is not a single operational definition for this construct. This discourse is evident as Larrive and Cooper (2006) revealed that the terms reflective inquiry, reflective thinking, reflective teaching, reflection, and reflective practice have been utilized synonymously. Due to this discrepancy Fat’hi and Behzadpou (2011) stress that it’s paramount to define lucidly what one intends when utilizing the term reflection. According to the pioneer Dewey (1933), “Active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends constitutes reflective thought” (p.6). Despite persistent ambiguity, the general consensus among scholars appears that reflection is an ongoing systematic, disciplined, back and forth mental activity of observing, questioning, analyzing, and refining thoughts/actions for gaining clarity in understanding and achieving productive outcomes (Dewey, 1933; Killion & Todnem, 1991; Bright, 1996; Cole & Knowles, 2000; Osterman & Kottkamp, 2004; Fat’hi & Behzadpou, 2011). What’s more, this form of inquiry has been deemed higher-level thinking (Lasley, 1992), cognitive risk-taking (Schon, 1987), and disciplined thinking balancing paucity and redundancy (Dewey, 1933). Interesting enough, reflective inquiry as a way of knowing and learning does not claim to provide answers; rather it’s a tool for professionals to pose thoughtful and significant questions to enhance the quality of their practice (Robinson et al., 2001). REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 5 Assumptions of Reflective Inquiry as a Way of Knowing Inquiry and Reflection Expose Blind Spots Deviating from the natural inclination to promote or advocate one’s agenda, inquiry through questioning, primarily, seeks to explore the assumptions or perspectives of others (Marquardt & Waddil, 2004). Accordingly, Larrive & Cooper (2006) affirmed that inquiry aims at exploring for the purpose of understanding; as a result, intrinsic orientation is transformed from certainty to curiosity. One assumption of this way of thinking is that by operating in a mode of protracted inquiry one will excavate blind and opaque spots (Dewey, 1933). Engaging in a cycle of open discovery helps to bring to light the hidden structure of one’s thinking, lying beneath the realm of consciousness. At a minimum, reflection serves as a tool for exposing unconscious mental models and as Kim (1999) avows emancipates us from deception. Correspondingly, Dewey (1933) declares, “All reflective inference presupposes some lack of understanding, a partial absence of meaning” (p.119). Inherent in this assertion is the need to acknowledge that perceptions are always somewhat distorted and impact professional practice. Thus, the way to achieve adequate knowledge is through being open-minded, suspending hasty conclusion, and mastering methods of inquiry (Dewey, 1933). Once hidden theories are discovered (Shapiro & Reiff, 1993), it forms the basis for considering alternative perspectives. Reflective Inquiry Challenges Established Beliefs Cole and Knowles (2000) articulated one of the fundamental assumptions of reflective inquiry is that ideologies behind all practice are subject to questioning, none exempt. Not only does this mode of inquiry encourage bringing to light embedded assumptions, but it also requires critically challenging any established beliefs or what Morgan (2006) refers to as psychic prisons favored ways of thinking that become traps. Correspondingly, Dewey (1933) states, “Thought REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 6 can more easily traverse an unexplored region than it can undo what has been so thoroughly done as to be ingrained in unconscious habit” (p.121). Thus, reflection becomes a platform for confronting entrenched mental models and testing dogmas; consistently asking questions into each phenomenon. Creating this mental discipline results in knowledge and experiences becoming informed and formed by reflective practice; allowing the practitioner to perpetually expand to a wide range of possibilities (Larrive & Cooper, 2006). Subsequently, as Schon (1987) proposes, one can frame and reframe problems, and, as they yield new discoveries continue in a spiral of reflection into those discoveries. Correspondingly, in this recursive process Copeland et al. (1993) explicate beyond consciousness of framing problems, the reflective practitioner generates and tests optimal solutions, and pursues action to deliberately incorporate new or enhanced understanding into practice. The authors deem both problem-solving and learning as critical constituents of reflection. Reflective Inquiry Facilitates Learning Reflective practice engenders that gaining a deeper understanding and insight will lead to effective learning. Accordingly, Van (1997) affirms reflection functions as a fundamental component and link in the learning process. The utility of reflecting back is to create future learning or in Dewey’s (1933) view its purpose is prospective. Under the constructivist paradigm learning is proactively generated by reflecting on past and current knowledge to create future learning (Fat’hi, 2011). In light of this view, Race (2002) supported that the deliberate act of reflecting significantly contributes to making sense of what was learned, why it was learned, and how that particular increment of learning was facilitated. Dewey (1933) has proclaimed that experience does not equal learning rather learning is derived from reflecting on experience. Consequently, reflective inquiry is a framework built on the notion that reflection enables REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 7 learning. Moreover, some contend not only is reflection a key building block to human learning but, it also supports and enhances deep learning (Moon, 1999). The ultimate purpose of reflective thinking is to engage in continuous learning by intentionally challenging prior learning (Van, 1997). In light of this view Argyris and Schon (1978) developed a model of reflection to distinguish effective and ineffective learning. They describe single loop learning as one dimensional and simplistic verses double loop learning which is multidimensional and authentically reflective, going deeper to examine the root of a dilemma. In view of that, Argyris and Schon (1978) would consider an educator, who discovers a blind spot or a dilemma and applies a problem-solving or pedagogical technique to correct it, as employing single loop learning. However, when teachers thoughtfully challenge their own entrenched mental models, openly consider alternatives, and modify their thinking by seeking to understand both the students and their perspectives, the authors would view them as effectively engaging in double loop learning. Taking it to the next level Isaacs (1993) proposed triple loop learning, this form of inquiry promotes the type of learning “that permits insight into the nature of paradigm itself, not merely an assessment of which paradigm is superior.” Incorporating double loop learning, where reflection is fundamental, he asserted the need to reflect on the process of learning itself for the purpose of learning. Fittingly, Mezirow, (1991) states that “reflective learning involves assessment or reassessment of assumptions” and is appreciated as a process that promotes or leads to transformative learning: a reflective process in which frames or reference or habits of the mind are transformed to become open and inclusive generating new frames that inform practice (Mezirow, 1991). Consistent with Mezirow’s perspective Cranton (1994) affirms that engaging in a critical level of reflection, where frame of reference has been reconstructed and is REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 8 demonstrated in action, signifies transformative learning. Moreover, confirming this notion Van (1997) declares “reflection and transformative learning are the tenets of reflective practice as ways of knowing and the nature of learning are interconnected.” Accordingly, the literature progresses to view teachers as self-reflective agents who can deepen their understanding of themselves and their students and who can, on the basis of that insight, act to change the conditions of their institutions (Carrington & Selva, 2010). Research Implications of Reflective Inquiry The ramifications of the research on reflection, since its peak in the 90’s, have had a tremendous impact in the field of teacher education and development; effective teaching has been positively correlated with inquiry and reflection (Harris, 1998), whereas unreflective teaching has been associated with low effectiveness (Robinson et al., 2001). Ample literature in the field reveals teacher’s beliefs have profound influences on their thoughts, decisions and instructional judgments (Williams & Burden, 1997; Woods, 1996). Thus, the role of reflective stance is to help educators become aware of their blind and opaque spots (Dewey, 1933) and challenge traditional theories to heighten the quality of their teaching and self-assessment (Robinson et al., 2001). What’s more, by being encouraged to challenge their preconceived notions teachers gain insight into their implicit or deep-rooted theories, this forms the basis for not only reinforcing them to identify their misconceptions, but also for transforming their erroneous conceptions to improve pedagogical practice (Leloup, 1995; Woods, 1996). Engaging in reflective practice allows teachers to examine how they interact with students i.e. if their theories-in-use are consistent with their espoused theories (Schon, 1983). Examining such philosophies creates an avenue for teachers to successfully bridge the gap between theory and practice, leaving them both enlightened and emancipated to make the necessary changes REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 9 (Robinson et al., 2001). As teachers gain conscious awareness into their guiding principles, values, and/or beliefs they respond to make their instructional practices fruitful. Similarly, Lyons (2006) discovered patterns of reorientation and reconsideration applied into their activities of teaching. Reflective teachers are empowered to amalgamate their critically examined theories into their teaching and learning practices, as well as inspired to proactively engage in educational decisions (Robinson et al., 2001). Furthermore, research reveals some benefits of reflective practice include: increased teacher’s sense of self-efficacy, high level proficiency in novice teachers, shift from single loop to double loop learning, teacher job satisfaction, enhanced interpersonal relationship among colleagues and students (Irvin, 2009), expanded professional development (Caceres & Chamoso, 2008) and enhanced potential to succeed and thrive (Robinson et al., 2001). Reflective Inquiry as My New Way of Knowing One of my previous ways of knowing has been that what I am taught in school is to be accepted as final authority. I had nonchalantly accepted the dogmas presented to me throughout my educational endeavors. As an undergraduate major in Industrial/Organizational Psychology, I was provided with formulas and methodologies and if I could replicate predictability and control, then it was considered peak performance. Accordingly, the predetermined set of criteria, I had been supplied with, had to be applied meticulously. The idea of deviating from technical rationality would have disturbed me. I was conditioned to believe that there is always a rigorous method to perform optimally. Consequently, I had a rigid mentality where most things were deemed black or white. It had not occurred to me that I should bring various notions into question. I, unconsciously, operated under this humble schema: Who am I to question what has been masterfully comprised by scholars and researchers in the field? Consequently, I adhered to REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 10 established guidelines in order to carry tasks out right. Disparately, reflective inquiry challenges me to ask if I’m I even doing the right things. It encourages me to explore dimensions that I had not previously considered. I now grasp the fundamental component of learning is to operate in a life-long stance of inquiry. Accordingly, adopting a reflective stance has compelled me to distinguish, reality is complex and nothing, under the sun, lies in the realm of certainty. Festinger states, “The theory of cognitive dissonance holds that when we experience dissonance we are motivated to change one, or the other, of the cognitions so that they are more consistent” (p.3). Indeed, it was difficult for me to let go of the narrow mechanical approach I had adopted. I had to acknowledge my cognitive fallacies and surrender my entrenched mental frameworks. This new way of knowing has helped me to deconstruct or peel the layers of my prior learning. I’m learning how to nurture the ability to think critically and reciprocally between two opposing points while suspending judgment (Dewey, 1933). I’m gaining new consciousness into the deep structures and embedded assumptions that significantly shape my perspective and inevitably inform my practice. As I’m being transformed into a reflective practitioner, I find, I’m reconstructing how I think about my thinking. I’m astute and acknowledge that my biases have the potential to influence both my research activities and instructional practices. Therefore, my goal is to be conscientious about my practices. I discern the need to operate in a mode of active inquiry. In light of this commitment, I’ll continually reevaluate my theories and distorted perceptions, remaining open to that which I do and do not anticipate. As I engage in a self-study of systematically slow down my thinking, turning things over, and suspending conclusion (Dewey,1933), I noticed a cognitive shift beginning to take place within me, transforming my learning experiences. On this path to achieving a PhD and thereafter, I have made a commitment to further cultivate this keen mental discipline in my personal and professional life. REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 11 References Argyris C., & Schön D. A. (1978). Organizational learning. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Bright, B. (1996). Reflecting on “reflective practice.” Studies in the Education of Adults, 28(2), 162-184. Caceres, M.J. and Chamoso, J. (in press) Analysis of the reflections of student teachers of mathematics when working with learning portfolios in spanish university classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education (in press). Carrington, S., & Selva, G. (2010). Critical social theory and transformative learning: Evidence in pre-service teachers' service-learning reflection logs. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 45-57. doi:10.1080/07294360903421384. Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (2000). Researching Teaching: Exploring teacher development through reflective inquiry. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Copeland, W. D., Birmingham, C., De La Cruz, E., & Lewin B. (1993). The reflective practitioner in teaching: Toward a research agenda. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9, 347-359. Cranton, P. (1994). Understanding and promoting transformative learning. San Francisco: Jossey-bass Publishers 3-21. Danziger, K. (1980), The history of introspection reconsidered. Journal of History Behavior Science.16: 241–262 doi: 10.1002/1520-6696(198007). Dewey, John. (1997). How we think. New York: Dover Publications. REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 12 Fat’hi, J. & Behzadpou, F. (2011).Beyond method: The rise of reflective teaching. International Journal of English Linguistics. Vol. 1, No. 2 doi:10.5539/ijel.v1n2p24 Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson. Harris, A. (1998). Effective teaching: A review of the literature. School Leadership and Management, 18(2), 169-183. Irvin, L. (2009) What previous research reveals about rhetorical reflection. http://www.lirvin.net/liresearch/What%20Previous%20Research%20Reveals.pdf. Isaacs, W.N. (1993). Taking flight: dialogue, collective Thinking, and organizational Learning. Organizational Dynamics, 22 (2). Killion, J., & Todnem, G. (1991). A process of personal theory building. Educational Leadership, 48(6), 14-17. Kim, H. S. (1999) Critical reflective inquiry for knowledge development in nursing practice Advanced Nursing, 29(5), 1205-1212. Lasley, T. J. (1992). Inquiry and reflection: Promoting teacher reflection. Journal of Staff Development, 13(1), 24-29. LeLoup, J. (1995). Pre-service foreign language teacher beliefs: Expectations of excellence: preparing for our future. NYSAFLT Annual Meeting Series 12, 137-146. Marquardt, M. & Waddil, D. (2004). The power of learning in action learning: a conceptual analysis of how the five schools of adult learning theories are incorporated within the practice of action learning. Action Learning: Research and Practice.1 (2) DOI:10.1080/1476733042000264146. Mezirow, J, (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Moon, J. (1999) Reflection in learning and professional development. London: Kogan Page. REFLECTIVE INQUIRY 13 Morgan, G. (2006). Images of organization. California: Sage Publications, Inc. Osterman, K. P., & Kottkamp, R. B. (2004). Reflective practice for educators: Improving schooling through professional development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Robinson, E. T., Anderson-Harper, H. M., & Kochan, F. K. (2001). Strategies to improve reflective teaching. Journal of Pharmacy Teaching, 8(4), 49. Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. Schon, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass . Shapiro S.B. & Reiff J. (1993) A framework for reflective inquiry on practice: Beyond intuition and experience. Psychological Reports 73, 1379-1394 Swindal, J. (1999). Reflection revisited: Jurgen Habermas's discursive theory of truth. New York: Fordham University Press. Lyons, N., (2006). Reflective engagement as professional development in the lives of university teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 12 (2), 151–168 Van Halen-Faber, C. (1997). Encouraging critical reflection in pre-service teacher education: a narrative of a personal. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, (74), 51. Williams, M. and Burden, R. L. (1997) Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. New York: Cambridge University Press. REFLECTIVE INQUIRY Woods, D., (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching: Beliefs, decision-making and classroom practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 14