File

advertisement

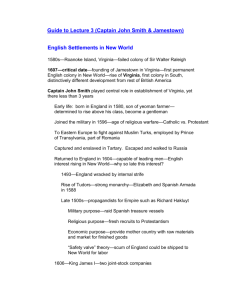

(Please Check) Lincoln Memorial University Carters & Moyers School of Education Undergraduate: _____ or Formal Lesson Plan Format M. Ed: ______ Student name(s): Rachel Anderson_________ Education Course(s): EDUC 591___________________ School: Jefferson Middle School___ Grade: 8th______ Subject(s): _US History________________ Cooperating Teacher's Signature: _________________Date(s): _9/26/13______________ I. State Standards: A. 5.02: I can understand the place of historical events in the context of past, present and futre B. 5.03: I can use historical information acquired from a variety of sources to develop critical sensitivities such as skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts. II. Lesson Title and or Unit Title: Pocahontas and John Smith: What Happened Between Them Anyway? / Jamestown and Plymouth III. Instructional Objectives: A. B. C. TSW analyze primary and secondary documents regarding the first encounter between John Smith and the Powhatan Chief by completing the graphic organizer. TSW compare and contrast two different historians’ arguments regarding this same encounter through classroom discussion. TSW formulate their own interpretation of the event and John Smith’s retelling of it by completing the graphic organizer. Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy: Highlight or Circle those used in this lesson Level I (Remembering) – recalling information, recognizing, listing, describing, retrieving, naming, finding Level II (Understanding) – explaining ideas or concepts, interpreting, summarizing, paraphrasing, classifying, explaining Level III (Applying) – using information in another familiar situation, implementing, using, executing Level IV (Analyzing) – breaking information into parts to explore understandings and relationships, comparing, organizing, deconstructing, finding, investigating Level V (Evaluating) – justifying a decision or course of action, checking, hypothesizing, critiquing, experimenting, judging Level VI (Creating) – generating new ideas, products, or ways of viewing things, designing, constructing, planning, producing, inventing Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences: Verbal Linguistic (“word smart”) Logical-Mathematical (“number / reasoning smart”) Visual Sin groups,patial (“picture smart”) Musical Rhythmic (“music smart”) Interpersonal (“people smart”) Intrapersonal (“self smart”) Bodily-Kinesthetic (“body smart”) Naturalist (“nature smart”) IV. Prior Knowledge: The Age of Exploration, The Spanish Conquest, The Spanish Armada V. Technology/Media/ Materials: A. B. C. D. E. Walt Disney’s Pocahontas Movie (Segment where Pocahontas saves John Smith) Copies of Pocahontas Timeline Copies of Pocahontas Documents A and B Copies of Historian Interpretations A and B Copies of Pocahontas Worksheets VI. Instructional Plan A. B. Set: TTW ask students about their prior knowledge of Pocahontas. TTW facilitate a short discussion, finally leading them to the question, “Did Pocahontas save John Smith’s life?” Following their answers, TTW play a short video clip from Walt Disney’s Pocahontas (Segment where Pocahontas saves John Smith’s life). TTW then ask the students what they noticed about the video. Was it true? So, do you believe the movie? Is this what actually happened between Pocahontas and John Smith? Essential Questions: i. What was the relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith? ii. How do historians research the “truth?” C. Instructional Sequence i. TTW handout Timeline, John Smith Documents A & B, and John Smith documents worksheet. TSW read the documents individually. ii. TTW facilitate a short classroom discussion. What was the main point of Document A? Document B? Why would there be two different versions of the same event? iii. TSW split into groups (columns) and complete the graphic organizer together. iv. TTW facilitate another short classroom discussion, asking students the last two questions. Why would JS have lied about the encounter on the second telling? Why would he have waited to reveal the truth? v. TTW go over the difference between primary and secondary documents. TTW hand out Historian Interpretations A and B (1/2 of the class gets one or the other). TSW read the opposing viewpoints. vi. TTW facilitate class discussion: 1. Which historian did students find more convincing? Why? 2. What evidence did both historians use to support their argument? 3. Could there be a third interpretation? 4. What did the movie get right and what did it get wrong? Why would Disney choose to make the movie that way? vii. Closing: Discussion about historical inquiry. In history, most evidence is written in documents. When we read those documents, we have to ask certain questions: 1. Who wrote the document? 2. Why did they write it? 3. What else was going on at the time? 4. Do other sources agree or disagree with this account? VII. Practice and Review: TS experience analyzing documents on their own at first individually. They then have the opportunity to discuss the information with their peers in groups. After this, we speak about the documents as a whole class, making sure they understand the main points of the documents. We compare and contrast them together so that everyone has an opportunity to review the information together. VIII. Learner Involvement: TS are involved throughout the duration of the lesson by actively reading then filling out the graphic organizer in groups. They are then actively involved by participating in a class discussion. IX. Learner Environment: TTW show the video clip for the visual learners, creating an inclusinve environment catered to all learners X. Closure: TSW answer one of the essential questions on a notecard. XI. Modifications / Accommodations: XII. Method of Assessment: Formative (Informal) Assessment: Classroom Discussion, Small Group Discussion Summative (Formal) Assessment: Graphic Organizer and Closure Exit Ticket Identify assessment strategy(ies) and attach a copy of the assessment to the lesson plan. XIII. Method of Re-teaching: If I were to re-teach this lesson, I would find other documents to use that emphasize the point. I would have big sheets of paper around the room and have the students write down their ideas on the paper, analyzing whether or not John Smith was lying or telling the truth. XIV. Reflection: Include a reflection on how the lesson was taught, did you accomplish the objectives, how did the students react, was your teaching effective, etc and plans for what you will do in the next lesson, if applicable. To be honest, this was a really difficult lesson for my students. They have been so used to taking multiple-choice exams that they have not fully developed critical-thinking skills. For the most part, my students are still developing the skills to look at a passage, determine the main idea, identify possible motives, and find quotes to support one’s argument. In saying this, I believe this lesson was invaluable because it is teaching them these skills in baby steps. To help scaffold their learning, I provided my students with a graphic organizer that took them through each step in the process. After they had read the passages, we spent time as a class discussing answers. By doing this, I could gage their understanding of the main concepts. While the students worked in their groups completing the graphic organizers, I monitored and adjusted. I would stop and talk with some groups, helping them get to the correct answer. Finally, I collected the graphic organizers and assessed student learning by grading these. While grading, I came to the conclusion that this lesson as a whole was a success. Because my students were given the opportunity to work individually, then with a small group, then with the class as a whole discussing answers, almost all of them grasped the concept. My strategies for this lesson were to providing them with a handout that served as a scaffolding tool, helping help them achieve the main goal of the lesson. Also, I used the “Think. Pair. Share.” concept, so that students worked, giving them an opportunity to see if they understand the concept when working along, in small groups, and with the entire class. I learned that these concepts benefited student learning in my eighth grade class. At Jefferson, I taught the same class five times. For this particular lesson, I tweaked it throughout the day, improving student learning. After the first class, I went through an entire example of my expectations with the class before asking them to try on their own. I read the passage out loud to the class and asked them the questions on the handout, prompting them to the correct response. By doing this, more of my students succeeded when doing the second passage on their own because they understood exactly how to complete the assignment. If I were to re-teach this lesson, I would find a historical event that actually had a “truth” to be discovered. For this lesson, no one knows for sure what exactly happened between John Smith and Pocahontas. There are different interpretations to compare and contrast and the students can analyze possible motives for these different stories, however, there is no actual “truth.” My students found this abstract idea a bit too difficult. They did not understand the purpose of analyzing simply for the sake of analyzing, they wanted there to be a concrete answer. Next time, I will try to find a historical mystery where there is a “truth” to be found. Reference List Lesson Plan Ideas from: http://sheg.stanford.edu/pocahontas John Smith, General History of Virginia, New England and the Summer Isles, 1624. http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/smith/smith.html Paul Lewis, The Great Rogue: A Biography of Captain John Smith, 1966, (172-173). J.A. Lewo Lemany, The American Dream of Captain John Smith, 1991. Document A: “True Relation” (Modified) Arriving in Werowocomoco, the emperor welcomed me with good words and great platters of food. He promised me his friendship and my freedom within four days…He asked me why we came and why we went further with our boat…He promised to give me what I wanted and to feed us if we made him hatchets and copper. I promised to do this. And so, with all this kindness, he sent me home. Source: Smith’s own words, from A True Relation of such occurrences and accidents of note as hath happened in Virginia Since the First Planting of that Colony, published in 1608. Document B: “General History” (Modified) They brought me to Meronocomoc, where I saw Powhatan, their Emperor. Two great stones were brought before Powhatan. Then I was dragged by many hands, and they laid my head on the stones, ready to beat out my brains. Pocahontas, the King’s dearest daughter, took my head in her arms and laid down her own upon it to save me from death. Then the Emperor said I should live. Two days later, Powhatan met me and said we were friends. He told me to bring him two guns and a grindstone and he would consider me his son. Source: From Smith’s later version of the story in General History of Virginia, New England and the Summer Isles, published in 1624. John Smith Documents Worksheet Did Pocahontas save John Smith’s life? Document A: “True Relation” says Document B: “General History” says Why would Smith add on to his earlier story? Why might Smith lie or exaggerate and invent new information? Why wouldn’t Smith lie about the story? Paul Lewis Historian, Interpretation A (Modified) Author, The Great Rogue: A Biography of Captain John Smith (1966) In 1617, Pocahontas became a big media event in London. She was a “princess” (daughter of “king” Powhatan), and the first Indian woman to visit England. Because she converted to Christianity, people high in the church, as well as the King and Queen, paid attention to her. While all this was going on, John Smith published a new version of True Relation, adding footnotes that say that Pocahontas threw herself on Smith to save him. Smith even takes credit for introducing Pocahontas to the English language and the Bible. Then, in 1624, Smith expands his story in General History. He adds details to the story, and says that Pocahontas risked her life to save his. Why would a chief who had been so friendly before, suddenly decide to kill John Smith? Source: Excerpt from the Great Rogue: A Biography of Captain John Smith, written by the historian Paul Lewis in 1966. J.A. Leo Lemay Historian, Interpretation B (Modified) Author, The American Dream of Captain John Smith (1991) John Smith had no reason to lie. In all of his other writings he is very accurate and observant. For 250 years after his captivity, no one questioned his story. The reason the two versions differ is that their purpose is different. In A True Relation, Smith didn’t want to brag about his adventures, he wanted to inform readers about the land and people of Virginia. In the General History, his goal was to promote settlement in Virginia (and added stories might get people interested). There is no doubt the event happened. Smith may have misunderstood what the whole thing meant. I think it was probably a common ritual for the tribe, where a young woman in the tribe pretends to save a newcomer as a way of welcoming him into the tribe. Source: Excerpt from The American Dream of Captain John Smith, written in 1991 by historian J.A. Leo Lemay. Historian Interpretation Worksheet Did Pocahontas save John Smith’s life? Paul Lewis says J.A. Leo Lemay says Which historian interpretation do you find more convincing? Why? Document A: “True Relation” (Original) Arriving at Weramocomoco [? On or about 5 January 1608], their Emperor proudly lying upon a Bedstead a foot high, upon ten or twelves mats, richly hung with many chains of great pearls about his neck, and covered with a great covering of Rahaughcums. At head sat a woman, at his feet another; on each side sitting upon a mat upon the ground, were ranged his chief men on each side of the fire, ten in a rank, and behind them as many young women, each a great chain of white beads over their shoulders, their heads painted in red: and with such a grave and majestic countenance, as draw me into admiration to see such state in a naked savage. He kindly welcomed me with such good words, and great platters of sundry victuals, assuring me his friendship, and my liberty within four days...He asked me the cause of our coming…He demanded why we went further with our Boat…He promised to give me corn, venison, or what I wanted to feed us: hatchets and copper we should make him, and none should disturb us. This request I promised to perform: and thus, having with all the kindness he could devise, sought to content me, he sent me home, with 4 men: one that usually carried my gown and knapsack after me, two other loaded with bread, and one to accompany me. Source: Smith’s own words, from A True Relation of such occurrences and accidents of note as hath happened in Virginia Since the First Planting of that Colony, published in 1608. Document B: “General History” (Original) At last they brought him [Smith] to Meronocomoco, where was Powhatan their Emperor…[T]wo great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on him [Smith], dragged him to them, and theron laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the King’s dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms and laid her own upon his to save him from death: whereat the Emperor was contended he should live… Two days after, Powhatan having disguised himself in the most fearefullest manner he could, caused Capt. Smith to be brought forth to a great house in the woods…then Powhatan…came unto him and told him now they were friends, and presently he should go to Jamestown, to send him two great guns, and a grindstone, for which he would give him the Country of Capahowosick, and forever esteem him as his son Nantaquoud. Source: From Smith’s later version of the story in General History of Virginia, New England and the Summer Isles, published in 1624. Paul Lewis Historian, Interpretation A (Original) Author, The Great Rogue: A Biography of Captain John Smith (1966) [Pocahontas] first steps onto the stage in 1617, a few months after she and her husband, John Rolfe, arrived in England. A charming, attractive, and exceptionally intelligent young woman, she created a sensation everywhere she went. Not only was she the daughter of a king and the first Indian woman ever to visit the British Isles, but as a convert to Christianity she aroused interest in circles that otherwise would have ignored her. She discussed theology with bishops and with those learned scholars who were engaged in the monumental task of translating the Bible from Hebrew and Greek for King James, who had ordered a new edition published. She proved to the doubting dons of Oxford and Cambridge that she was an independent, stimulating thinker. Her beauty and sweetness endeared her to the court, where Queen Ann became her patroness, and even the sour James unbent and chatted with her by the hour. While Pocahontas was enjoying her triumph, a new edition of John [Smith]’s True Relation was published. It was substantially the same book that had been printed eight years earlier, and the text was not altered. But there was something new in the form of a series of running footnotes in the section that dealt with his capture by the Chesapeake late in 1607. These notes tell the story, subsequently learned by generation after generation of children, of Pocahontas’ courage and heroism…Without making the claim in so many words, he hints that he taught her to speak English and that she acquired her love of the Bible from him… A longer, more smoothly written version of the story appears in The General History of Virginia, which John completed in 1624 and published in that same year. In it he expands on the theme that she rescued him at the risk of her own life. “Princess Pocahontas hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine,” he declares. “Not only that, but she so prevailed with her father that I was safely conducted to Jamestown”…. The alleged ire of Powhatan and his order condemning John to death do not jibe with the consistently friendly attitude he had displayed previously. Source: Excerpt from The Great Rogue: A Biography of Captain John Smith, written by the historian Paul Lewish in 1966, (pp. 172-173). J.A. Leo Lemay Historian, Interpretation B (Original) No one in Smith’s day ever expressed doubt about the episode, and may persons who must have known the truth—including John Rolfe, Pocahontas, her sister, and brother-in-law—were in London in 1616 when Smith publicized the story in a letter to the queen. As for the exact nature of the event, it seems probable that Smith was being ritualistically killed. Reborn, he was adopted into the tribe, with Pocahontas as his sponsor. But Smith, of course, did not realize the nature of the initiation ceremony. Source: Excerpt from The American Dream of Captain Smith, written in 1991 by historian J.A. Leo Leman.