Mayer`s principles for the design of 21st century multimedia

advertisement

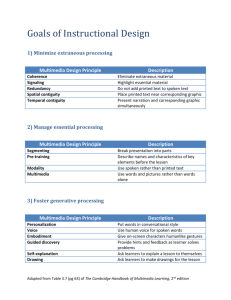

Mayer's principles for the design of 21st century multimedia learning Daphne Tseng Department of Learnig Technologies, University of North Texas United States DaphneCYTseng@mynut.edu Abstract: Richard E. Mayer proposed twelve principles of design an effective multimedia learning decade ago. These principles were discussed, revised, replicated, and re-examined by global researchers to adopt them to different learning situations. The goal of this session is to reexamine and update Mayer’s principles into 21st century multimedia learning design. In this session, the presenter will share and discuss 1) briefly about Mayer's principles of multimedia learning design; 2) current researches about multimedia learning design based on Mayer’s principles, and 3) how to adopt these principles into multicultural and multigenerational learning setting. Introduction After Richard E. Mayer published his book “Multimedia learning”, his twelve multimedia learning design principles are well discussed by the not only educational psychology field but also instructional design field. A longstanding debate exists surrounding what should and should not be included in multimedia learning design (Muller, et al., 2008). Some of the principles provide a good guidance for instructional designers to design the products and delivery the learning material with multimedia format; other principles remain the space for researcher and designer to examine. For instance, the redundancy principle is revised by Mayer and Johnson (2008); the modality principle is replicated with the same or different kind of learning materials (e.g. De Westelinck, et al., 2005; Mann, et al., 2002; Tabbers, et al., 2004; Tabbers & Spoel, 2011; Witteman & Segers, 2010); the segmenting principle is examined by Lusk et al. to emphasis the importance of individual difference variable would effects learning in a multimedia instructional environment (2009); the coherence principle is noted that irrelevant information to a multimedia treatment is not necessary, but it will maintain the attention from learner to promote the learning effectiveness (Muller, et al., 2008). Discussion Mayer’s twelve principles can be categorized by different intentions. First of all, the coherence, signaling, redundancy, spatial and temporal principles are intended to reduce extraneous processing during learning (Mayer, 2009). Mayer claims that the coherence principle is based on the knowledge-construction view of learning, meaning that eliminating interesting but irrelevant materials (e.g. words, image, sound, music) would assist learners learning actively. However, the opposing viewpoint supports the idea that interest plays a key role in allocating limited cognitive resources (Schank, 1979). To add seductive details into instruction could help to catch and hold learner’s interest during instruction to improve retention (Mitchell, 1993). Thus, Muller et al (2008) reported that by adding approximately 50% extra interesting but irrelevant information to a multimedia treatment did not result in lower achievement on a post –test as would be predicted by the coherence principle. The additional interesting information served a useful function, maintaining attention in the authentic learning setting employed in the experiment. The redundancy principle was revised by Mayer and Johnson in 2008. Previous research has shown that students learn better from multimedia lessons containing graphics and narration than from graphics, narration, and on screen text (Moreno & Mayer, 2002). According to the cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer, 2001), because of meaningful learning occurs when learners are able to pay attention to relevant portions of the words and graphics as they are registered in sensory memory. However, Mayer and Johnson found out that if the on screen text is appeared near by the image and narration, and also briefly and highlight the content, it would help learner to learn. The second category of multimedia learning principles contains the concepts of segmenting, pre-training, and modality principle. These are intended to manage essential processing during learning (Mayer, 2009). The segmentation principle simply states that a multimedia tutorial that provides the user with pacing control, through use of a Start/Stop button or continue button, will result in greater learning than a tutorial that plays from beginning to end (Mayer & Chandler, 2001). By providing this self-information flow, it allows learners to process the information more deeply and will result in enhanced learning. Lusk et al (2009) emphasizes that individuals with different working memory capacity requires different basic (recall) and deep (application) knowledge acquisition. These individual variables will affects learning in a multimedia instruction environment. However, the modality principle could not always be replicated with different kind of learning materials (i.g. De Westelinck, et al., 2005; Mann, et al., 2002; Tabbers, et al., 2004; Tabbers & Spoel, 2011; Witteman & Segers, 2010). These authors have thus argued that the modality principle may only apply to short system-paced multimedia, and instructions within the technical domain. Based on these result, it was concluded that spoken text and visual text do not seem to tax working memory differently, and challenging the different channels assumption as an explanation for the modality effect. (Gyselinck et al. 2008, Tabbers, et al., 2011). Sixty students of communication and people from other backgrounds but with a degree in higher education participated Tabbers et al. (2011) research, and the experiment was failure to replicate the modality principle using exactly the same materials as Mayer and Moreno used in their 1998 and 1999 studies is a remarkable finding. Although many studies have found the modality effect, especially with system-paced multimedia materials on more technical subjects; the modality effect might not be as large as assumed in the literature, and that several boundary conditions may play a role in its occurrence. (Tabbers, et al., 2011). The Third category of multimedia learning principles contains the concepts of multimedia, personalization, voice, and image. Those principles are aimed at fostering generative processing during learning. A deeper kind of learning occurs when learners are able to integrate pictorial and verbal representations of the same message. Based on the personalization principle, multimedia instructional message should be presented in conversational style rather than formal style (Mayer, 2009). In the voice principle, Mayer indicated that learner performs better when they received human-voice instruction than machine-voice instruction. He also claims that people do not necessarily learn more deeply from a multimedia presentation when the speaker’s image is on the screen rather than not on the screen (Mayer, 2009). Conclusions Although Mayer’s principles provide guidance for educator and multimedia designer to design the learning materials and improve learner’s learning. However, the multimedia instructional technologies as well as the educational environment has been changing rapidly through the years. In this session, presenter will discuss these multimedia learning design principles, such as how those learner’s response with coherence, redundancy, modality, and voice principle when they learning second language; and how this twelve principles could benefit multicultural learning background. On the other hand, attendants will invite to share their valuable experience about multimedia learning design and opinion of improving learner’s learning experience. Reference De Westelinck, K., Valcke, M., De Craene, B. & Krischner, P. (2005). The cognitive theory of multimedia learning in the social sciences knowledge domain: Limitations of external graphical representation. Computers in Human Behavior, 21, 555-573. Gyselinck, V., Jamet, E. & Dubois, V. (2008). The role of working memory components in multimedia comprehension. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 353-374. Lusk, D. L., Evans, A. D., Jeffery, T. R., Palmer, K. R., Wikstrom, C. S. & Doolittle, P. E., (2009). Multimedia learning and individual differences: Mediating the effects of working memory capacity with segmentation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 636-651. Mann, B. L. Newhouse, P., Pagram, J., Campball, A. & Schulz, H. (2002). A comparison of temporal speech and text cueing in educational multimedia. Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning, 18, 296-308. Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mayer, R. E. (2008). Revising the redundancy principle in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 100(2), 380-386. Mayer, R. E. & Moreno, R. (1998). A split attention effect in multimedia learning: Evidence for dual processing systems in working memory. Journal of Educational Psychology. 84, 444-452. Mayer, R. E. & Moreno, R. (2002). Learning science in virtual reality multimedia environments: Role of method and media. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 598-610. Mayer, R. E. & Moreno, R. (2002). Verbal redundancy in multimedia learning: When reading helps listening. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 156-163. Mayer, R. E. & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychology, 38, 43-52. Mitchell, M. (1993). Situational interest: Its multifaceted structure in the secondary school mathematics classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology.m 85, 424-436. Moreno, R. & Mayer, R. E. (1999). Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 358-368. Muller, D. A., Lee, K. J. & Sharma, M. D., Coherence or interest: Which is most important in online multimedia learning? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 24(2), 211-221. Schank, R. C. (1979). Interestingness: Controlling inference. Artifical Intelligence, 12, 273-297. Tabbers, H. J., & Spoel, W. (2011). Where did the modality principle in multimedia learning go? A double replication failure that questions both theory and practical use. Zeitschrift fur Padagogische psychologie, 25(4), 221-230. Tabbers, H. J., Martens, R. L. & Van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2004). Multimedia instructions and cognitive load theory: Effects of modality and cueing. British Journal of Educational Psychology Review, 74, 71-81. Witteman, M. J. & Segers, E. (2010). The modality effect tested in children in a user-paced multimedia environment. Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning, 26, 132-142.