Click here to read our recent Op-Ed in major newspapers in Montana.

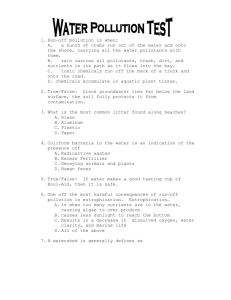

advertisement

Clearing the Water: What EPA’s New Clean Water Rule Means for Montana (and the West) It’s officially summertime in Montana! For many the recent heatwave was a potent reminder of just how much we appreciate our state’s great rivers and look forward to rafting, swimming, fishing, and good old-fashioned relaxation on the water. Unfortunately Montana’s water - and the important outdoors economy it supports - were recently risked by the EPA’s new Clean Water Rule. EPA’s new Clean Water Rule was intended as an update to the 43-year old Clean Water Act, needed because of recent confusion over the extent of pollution controls over headwater creeks, springs, and seeps. The rule was the product of a laborious review process by an EPA-appointed, 52-member Science Advisory Board, which reviewed and made use of an unprecedented 1,200 scientific articles describing what it takes to protect rivers, lakes, and streams across America. Unfortunately, the final rule – published only a few weeks ago – significantly diverges from the draft shared with the public by ignoring critical parts of the Science Advisory Board’s recommendations on issues that directly impact Montanans, not to mention the American West. EPA’s new rule threatens hundreds of headwater streams in mountainous Montana – and untold thousands throughout the West – with less protections and more pollution. It decreases the number and amount of waterways that are protected under law, it contains significant new exemptions and loopholes for big polluters, and fails to provide the clarity needed to prevent case-by-case determinations that unnecessarily risk American waterways with pollution. Critical for Montana, EPA’s new rule did not keep the Science Advisory Board’s recommendation of including scientific language defining a “tributary” and a “perennial, intermittent, or ephemeral stream.” Instead, the rule uses arbitrary measurements such as a 4,000’ perimeter, and requiring a “high-water mark” and “bed and banks” in order for a waterway to be eligible for protection. As a semi-arid state, the majority of streams and creeks in Montana’s mountains and valleys only flow intermittently during late spring and summer, after snowmelt and don’t possess “high-water marks” or “bed and banks,” meaning they aren’t protected! Consider the implications: a recent spatial analysis showed that in Western Montana, approximately 48% of stream miles within native trout historical range are intermittent or ephemeral, and 59% of stream miles are headwater streams. Science has shown that protecting these upstream “ephemeral” or “intermittent” waterways is critical because they flow into – and therefore are “tributary” to – our downstream rivers and streams that flow year-round, and provide cool, clean flows critical to mainstem river health. Narrowing protections for headwaters and upstream tributaries means many waters in Montana, and the American West, will likely end up with more caseby-case jurisdictional determinations and long delays for all sorts of land-use projects as courts – not sound science – decide what is a stream deserving protection and what is not. Second, the new rule fails Montana and the West by clearly stating it protects fewer miles of waterways, and less water, than is currently protected under Clean Water Act regulations. The rule’s preamble states that “[t]he scope of jurisdiction in this rule is narrower than that under the existing regulation. Fewer waters will be defined as ‘waters of the United States’ under the rule than under the existing regulations, in part because the rule puts important qualifiers on some existing categories such as tributaries.” Equally bad, EPA’s new rule creates a surprising number of new exemptions and loopholes that can allow corporate polluters to further degrade local waterways. For example, factory farms and the fossil-fuel industry are given new exemptions from water quality controls. EPA’s new rule states that “[t]he agencies for the first time also establish by rule that certain ditches are excluded from jurisdiction…” The type of ditches excluded are those that can flow intermittently from polluting operations like factory farms and fracking sites, yet whose polluted contents end up in downstream waterways. Carving out new exemptions for polluters threatens to make some water quality problems in Montana that much worse. For instance, many folks know Montana’s rivers and fisheries are threatened by the growing problem of nutrient pollution. Excess nutrients in waterways causes eutrophication (noxious algal growth) which hurts our fisheries, limits our recreational opportunities, and can make treating water for domestic, municipal, and agricultural use far more expensive. It’s easy to cast blame for nutrient pollution on a city or industrial facility discharging wastewater and stormwater to a local creek. But what about a big feedlot or agricultural operation upland discharging manure and fertilizer into a ditch, which then flows into the same stream running through a city, downstream? Previously big operations discharging to adjacent creeks or ditches would’ve been required to implement meaningful, practical, pollution controls. Now, under EPA’s new rule it is not certain how that upland ditch or stream will be defined and if it can be held accountable for water pollution; if it’s defined as ephemeral or intermittent, it probably won’t not be covered by federal law, and that upstream pollution source won’t be addressed under the Clean Water Act and as discussed below, probably not under Montana state law. Indeed, from a policy standpoint EPA’s new rule is a huge disservice to Montana because our 2014/2015 legislators amended state pollution laws to reduce protections for clean water. Consider Senate Bill 325, which inverted the intent behind pollution controls by forbidding Montana from possessing laws more stringent than an applicable federal standard unless required by state law. E.g., rules intended as a starting point, or “floor” for pollution limits, are now a “ceiling” or final limit. Considering most of Montana’s clean water protections are specifically tied to an applicable federal standard this means that EPA’s clean water rule, with its limited scope, is now the de-facto maximum scope of protection afforded waterways in Montana. Make no mistake: lessening the scope of protections over pollution impacts in Montana’s headwaters is bad news for our downstream rivers and the important outdoors economy and communities they support. Equally troublesome is the fact that the Montana Attorney General’s Office is suing the EPA over its new rule, using taxpayer dollars – but instead of arguing for increased, sciencebased protections, our AG is arguing that the rule is illegal and a federal “over-reach.” In fact, our AG Tim Fox is on record saying that Montana has “established strong water protections tailored to the unique needs of our communities,” and that “Montanans know how to protect our waters.” As an organization that regularly reviews inadequate pollution permits and actively contests weak rules that fail to protect Montana’s water resources and communities, we can only conclude that Mr. Fox’s use of “unique” and “tailored to our communities” language is synonymous with “lax” and “unscientific.” Science shows that of the 13 major rivers in the Upper Missouri River Basin, every single river is failing to meet its quality standards for at least one pollutant of concern. Lax enforcement of existing pollution controls and a failure to proactively address the pollution impacts that trends like recurrent droughts and burgeoning suburban sprawl create has already harmed Montana’s water. Now, EPA’s rule further reduces protections, our legislators are curtailing statebased protections, and we have an Attorney General set on protecting the status quo – apparently a status quo of degradation. Montana’s rivers – and our pollution controls – need increased and improved protections, not more of the status quo. EPA’s clean water rule was a landmark opportunity to better protect Montana’s – and the West’s - water from pollution and ensure every waterway is drinkable, swimmable, and fishable as intended when the Clean Water Act passed into law over 40 years ago. Sadly, EPA’s new rule cherry picks sound science, arbitrarily weakens protections for our waters, and creates new pollution exemptions and definitional requirements that are likely to lead to more litigation in our courtrooms rather than cleaner water in our lakes, rivers, and streams. Guy Alsentzer is the Executive Director of Upper Missouri Waterkeeper, the only water advocacy organization exclusively dedicated to defending clean water and community health throughout the 25,000 sq. miles of SW and West-Central Montana’s Upper Missouri River Basin. Learn more online at www.uppermissouriwaterkeeper.org