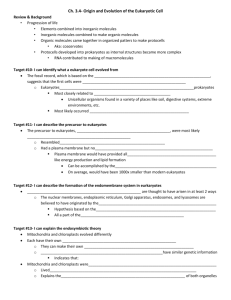

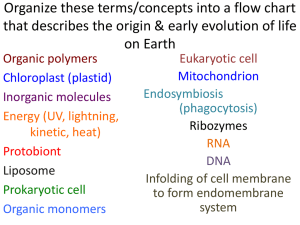

Endosymbiotic Theory: Origins & Evidence

advertisement

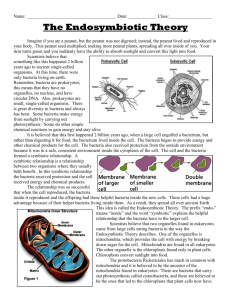

Endosymbiotic Theory The endosymbiotic theory concerns the origins of mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are organelles of eukaryotic cells. According to this theory, these originated as prokaryotic endosymbionts, which came to live inside eukaryotic cells. The theory postulates that the mitochondria evolved from aerobic bacteria (probably proteobacteria, related to the rickettsias), and that the chloroplast evolved from endosymbiotic cyanobacteria (autotrophic prokaryotes). The evidence for this theory is compelling as a whole, and it is now generally accepted. History The idea that the eukaryotic cell is a group of microorganisms was first suggested in the 1920s by the American biologist Ivan Wallin. The endosymbiont theory of mitochondria and chloroplasts was proposed by Lynn Margulis of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. In 1981, Margulis published Symbiosis in Cell Evolution in which she proposed that the eukaryotic cells originated as communities of interacting entities that joined together in a specific order. The prokaryote elements could have entered a host cell, perhaps as an ingested prey or as a parasite. Over time, the elements and the host could have developed a mutually beneficial interaction, later evolving in an obligatory symbiosis. Dr. Margulis has also proposed that eukaryotic flagella and cilia may have arisen from endosymbiotic spirochetes, but these organelles do not contain DNA and do not show any ultrastructural similarities to any prokaryotes, and as a result this idea does not have wide support. Margulis claims that symbiotic relationships are a major driving force behind evolution. According to Margulis and Sagan (1996), "Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking" (i.e., by cooperation, interaction, and mutual dependence between living organisms). She considers Darwin's notion of evolution driven by competition to be incomplete. Dr. Christian de Duve (winner of the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) proposes that peroxisomes may be the first endosymbionts, which allowed cells to withstand the growing amounts of free molecular oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere. Since peroxisomes have no DNA of their own, this proposal is more speculative than the above ideas. Evidence Evidence that mitochondria and chloroplasts arose via an ancient endosymbiosis of a bacteria is as follows: Both mitochondria and chloroplasts contain DNA, which is fairly different from that of the cell nucleus, and that is in a quantity similar to that of bacteria. Mitochondria utilize a different genetic code than the eukaryotic host cell; this code is very similar to bacteria and Archaea. They are surrounded by two or more membranes, and the innermost of these shows differences in composition compared to the other membranes in the cell. The composition is like that of a prokaryotic cell membrane. New mitochondria and chloroplasts are formed only through a process similar to binary fission. In some algae, such as Euglena, the chloroplasts can be destroyed by certain chemicals or prolonged absence of light without otherwise affecting the cell. In such a case, the chloroplasts will not regenerate. Much of the internal structure and biochemistry of chloroplasts, for instance the presence of thylakoids and particular chlorophylls, is very similar to that of cyanobacteria. Phylogenies built with bacteria, chloroplasts, and eukaryotic genomes also suggest that chloroplasts are most closely related to cyanobacteria. DNA sequence analysis and phylogeny suggests that nuclear DNA contains genes that probably came from the chloroplast. Some genes encoded in the nucleus are transported to the organelle, and both mitochondria and chloroplasts have unusually small genomes compared to other organisms. This is consistent with an increased dependence on the eukaryotic host after forming an endosymbiosis. Chloroplasts appear in very different groups of protists, which are in general more closely related to forms lacking them than to each other. This suggests that if chloroplasts originated as part of the cell, they did so multiple times, in which case their close similarity to each other is difficult to explain.