PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PERFECTIONISM & MINDFULNESS

advertisement

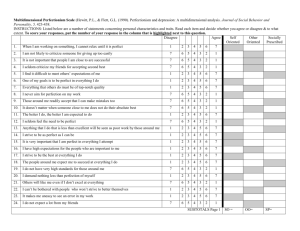

PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PERFECTIONISM & MINDFULNESS 1 Muhammad Abid Azam1, Paul Ritvo, 1, 2 & Joel Katz 1, 2 School of Kinesiology and Health Science, York University, Toronto, ON 2 Department of Psychology, York University, Toronto, ON Introduction This study aims to investigate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism (MP) and mindfulness meditation (MM) using physiological measures of stress—heart-rate variability (HRV) and respiration— as well as measures of visual attention (eye-tracking) and psychometrics. Perfectionist thinking has received attention for its association to anxietydepressive disorders (Sherry, Hewitt, Flett, & Harvey, 2003), chronic stress in sub-clinical populations (Pirbaglou et al., 2013), and mortality risks (Fry & Debats, 2009). Reduced HRV is found under conditions of worry (Brosschot, Van Dijk, & Thayer, 2007), and mental stress (Fabes & Eisenberg, 1997), while increased HRV has been found during conditions requiring self-regulatory effort (Segerstrom & Nes, 2007). Visual attention is implicated in anxiety disorders (Mogg et al., 2000) and attentional bias towards failure is a defined feature of perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991). It is hypothesized that perfectionists have reduced HRV compared to non-perfectionists, and perfectionists exhibit visual attention patterns suggestive of their attentional biases towards failure. This study employs a factorial design involving a sample of university students (N = 60) grouped into MP and non-perfectionists based on psychometric criteria. Students disclosing psychiatric and cardiovascular conditions are excluded from participating due to presenting potential confounds with the outcome measures. All participants undergo laboratory conditions of rest (5 minutes), stress (5 minutes), and afterwards are randomized to either an audio-guided MM condition or an eyes closed resting condition with audio merely describing MM (10 minutes). Participants are measured using an electrocardiogram and respiratory belt transducer during all three conditions. In the stress condition, participants perform a 22-trial pattern solving task presented through an eye-tracking monitor tracking fixations in specified areas of interest (AOI) on the screen. The trials present problem sets (Problem AOI) that appear solvable however, unknown to them, actually do not have correct or incorrect answers. The task is configured to indicate equal counts of correct and incorrect responses (Feedback AOI) by the end of the 22 trials. Perfectionists are expected to exhibit reduced HRV in the three conditions compared to non-perfectionists. Perfectionists are also expected to exhibit greater visual attention towards the feedback AOI and less visual attention to the problem AOI during the stress task. This study will help contribute to the literature on perfectionism by exploring previously uninvestigated relationships with important physiological health and stress markers (HRV and eye-tracking). This study will also inform MM interventions and programs looking to improve their effectiveness with populations known to have psychopathological risks. References Brosschot, J. F., Van Dijk, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2007). Daily worry is related to low heart rate variability during waking and the subsequent nocturnal sleep period. International Journal of Psychophysiology : Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 63(1), 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.07.016 Fabes, R., & Eisenberg, N. (1997). Regulatory Control and Adult’s Stress-Related Responses to Daily Events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(5), 1107–1117. Fry, P. S., & Debats, D. L. (2009). Perfectionism and the five-factor personality traits as predictors of mortality in older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(4), 513–24. doi:10.1177/1359105309103571 Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–70. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2027080 Mogg, K., McNamara, J., Powys, M., Rawlinson, H., Seiffer, A., & Bradley, B. P. (2000). Selective attention to threat: A test of two cognitive models of anxiety. Cognition & Emotion, 14(3), 375–399. doi:10.1080/026999300378888 Pirbaglou, M., Cribbie, R., Irvine, J., Radhu, N., Vora, K., & Ritvo, P. (2013). Perfectionism, anxiety, and depressive distress: evidence for the mediating role of negative automatic thoughts and anxiety sensitivity. Journal of American College Health : J of ACH, 61(8), 477–83. doi:10.1080/07448481.2013.833932 Segerstrom, S. C., & Nes, L. S. (2007). Heart rate variability reflects self-regulatory strength, effort, and fatigue. Psychological Science, 18(3), 275–81. doi:10.1111/j.14679280.2007.01888.x Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Harvey, M. (2003). Perfectionism dimensions, perfectionistic attitudes, dependent attitudes, and depression in psychiatric patients and university students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(3), 373–386. doi:10.1037/00220167.50.3.373