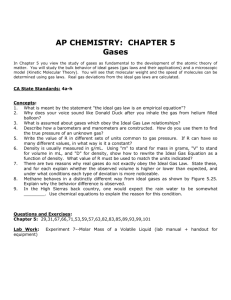

Lesson 5.1 properties of gases

advertisement

Lesson 5.1 The Properties of Gases Suggested Reading Zumdahl Chapter 5 Sections 5.1 Essential Questions What are the basic properties of gases? Learning Objectives Describe properties of gases. Introduction In this lesson we will look at some of the basic properties of gases. If you have a good understanding of this lesson, you will probably do well with the rest of the chapter content. The rest of the chapters deals with the laws that describe these properties and the applications that harness them. Therefore, you must have a good understanding of this content to make the rest of the chapter meaningful. The Properties of Gases Gases have four main characteristic properties: (1) they are easy to compress, (2) they expand to fill their containers, (3) they occupy far more space than the liquids or solids from which they form, and (4) they exert pressure on their surroundings. Compressability An internal combustion engine provides a good example of the ease with which gases can be compressed. In a typical four-stroke engine, the piston is first pulled out of the cylinder to create a partial vacuum, which draws a mixture of gasoline vapor and air into the cylinder (see figure below). The piston is then pushed into the cylinder, compressing the gasoline/air mixture to a fraction of its original volume. The ratio of the volume of the gas in the cylinder after the first stroke to its volume after the second stroke is the compression ratio of the engine. Modern cars run at compression ratios of about 9:1, which means the gasoline-air mixture in the cylinder is compressed by a factor of nine in the second stroke. After the gasoline/air mixture is compressed, the spark plug at the top of the cylinder fires and the resulting explosion pushes the piston out of the cylinder in the third stroke. Finally, the piston is pushed back into the cylinder in the fourth stroke, clearing out the exhaust gases. Liquids are much harder to compress than gases. They are so hard to compress that the hydraulic brake systems used in most cars operate on the principle that there is essentially no change in the volume of the brake fluid when pressure is applied to this liquid. Most solids are even harder to compress. The only exceptions belong to a rare class of compounds that includes natural and synthetic rubber. Most rubber balls that seem easy to compress, such as a racquetball, are filled with air, which is compressed when the ball is squeezed. Expandability Anyone who has walked into a kitchen where bread was baking has experienced the fact that gases expand to fill their containers. The air in the kitchen becomes filled with wonderful odors that are vapors from the baking bread diffusing into the room. Because gases expand to fill their containers, it is safe to assume that the volume of a gas is equal to the volume of its container. Remember this! Volumes of Gases The difference between the volume of a gas and the volume of the liquid or solid from which it forms can be illustrated with the following examples. One gram of liquid oxygen at its boiling point (-183oC) has a volume of 0.894 mL. The same amount of O2 gas at 0oC and atmospheric pressure has a volume of 700 mL, which is almost 800 times larger. Similar results are obtained when the volumes of solids and gases are compared. One gram of solid CO2 has a volume of 0.641 mL. At 0oC and atmospheric pressure, the same amount of CO2 gas has a volume of 556 mL, which is more than 850 times as large. As a general rule, the volume of a liquid or solid increases by a factor of about 800 when it forms a gas. This enormous change in volume is frequently used to do work. The steam engine, which brought about the industrial revolution, is based on the fact that water boils to form a gas (steam) that has a much larger volume. The gas therefore escapes from the container in which it was generated and the escaping steam can be made to do work. The same principle is at work when dynamite is used to blast rocks. In 1867, the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel discovered that the highly dangerous liquid explosive known as nitroglycerin could be absorbed onto clay or sawdust to produce a solid that was much more stable and therefore safer to use. When dynamite is detonated, the nitroglycerin decomposes to produce a mixture of CO2, H2O, N2, and O2 gases. 4C3H5N3O9(l) → 12CO2(g) + 10H2O(g) + 6N2(g) + O2(g) Because 29 moles of gas are produced for every four moles of liquid that decompose, and each mole of gas occupies a volume roughly 800 times larger than a mole of liquid, this reaction produces a shock wave that destroys anything in its vicinity. The same phenomenon occurs on a much smaller scale when we pop popcorn. When kernels of popcorn are heated in oil, the liquids inside the kernel turn into gases. The pressure that builds up inside the kernel is enormous and the kernel eventually explodes. Pressure The volume of a gas is one of its characteristic properties. Another characteristic property is the pressure the gas exerts on its surroundings. Many of us got our first exposure to the pressure of a gas when a bicycle tire went flat. Depending on the kind of bicycle we had, we added air to the tires until the pressure gauge read between 30 and 70 pounds per square inch (lb/in2 or psi). Two important properties of pressure can be obtained from this example. 1. The pressure of a gas becomes larger as more gas is added to the container. 2. Pressure is measured in units (such as lb/in2) that describe the force exerted by the gas divided by the area over which this force is distributed. The first conclusion can be summarized in the following relationship, where P is the pressure of the gas and n is the amount of gas in the container. P ∝n Because the pressure increases as gas is added to the container, P is directly proportional to n. This will come up again when we study Dalton's law of partial pressures. The second conclusion describes the relationship between pressure and force. Pressure is defined as the force exerted on an object divided by the area over which the force is distributed. The difference between pressure and force can be illustrated with an analogy based on a 10-penny nail, a hammer, and a piece of wood shown in the figure below. By resting the nail on its point, and hitting the head with the hammer, we can drive the nail into the wood. But what happens if we turn the nail over and rest the head of the nail against the wood? If we hit the nail with the same force, we can't get the nail to stick into the wood. When we hit the nail on the head, the force of this blow is applied to the very small area of the wood in contact with the sharp point of the nail, and the nail slips easily into the wood. But when we turn the nail over, and hit it on the point, the force is distributed over a much larger area. The force is now distributed over the surface of the wood that touches any part of the nail head. As a result, the pressure applied to the wood is much smaller and the nail just bounces off the wood. Example: Calculating Pressure Calculate the pressure exerted by a 200-lb man wearing size 10 shoes, if the area of each shoe in contact with the floor is 20 square inches. Using dimensional analysis we can see from the example above that the units of pressure are lbs/in2. Thus, we can see that we must divide the man's weight by the area of his shoes to obtain the appropriate answer. Pressure = Force ÷ Area = 200 lb ÷ 20 in2 = 10 lb/in2 Atmospheric Pressure What would happen if we bent a long piece of glass tubing into the shape of the letter U and then carefully filled one arm of this U-tube with water and the other arm with ethyl alcohol? Most people expect the height of the columns of liquid in the two arms of the tube to be the same. Experimentally, we find the results shown in the figure below. A 100-cm column of water balances a 127cm column of ethyl alcohol, regardless of the diameter of the glass tubing (To balance does not imply the fluids are equal in height. Rather, when in balance there is no net movement). We can explain this observation by comparing the densities of water (1.00 g/cm3) and ethyl alcohol (0.789 g/cm3). A column of water 100 cm tall exerts a pressure of 100 grams per square centimeter. A column of ethyl alcohol 127 cm tall exerts the same pressure. Because the pressure of the water pushing down on one arm of the U-tube is equal to the pressure of the alcohol pushing down on the other arm of the tube, the system is in balance. This demonstration provides the basis for understanding how a mercury barometer can be used to measure the pressure of the atmosphere. The Discovery of the Barometer In the early 1600s, Galileo argued that suction pumps were able to draw water from a well because of the "force of vacuum" inside the pump. After Galileo's death, the Italian mathematician and physicist Evangelista Torricelli (1608- 1647) proposed another explanation. He suggested that the air in our atmosphere has weight and that the force of the atmosphere pushing down on the surface of the water drives the water into the suction pump when it is evacuated. In 1646 Torricelli described an experiment in which a glass tube about a meter long was sealed at one end, filled with mercury, and then inverted into a dish filled with mercury, as shown in the figure below. Some, but not all, of the mercury drained out of the glass tube into the dish. Torricelli explained this by assuming that mercury drains from the glass tube until the force of the column of mercury pushing down on the inside of the tube exactly balances the force of the atmosphere pushing down on the surface of the liquid outside the tube. Torricelli predicted that the height of the mercury column would change from day to day as the pressure of the atmosphere changed. Today, his apparatus is known as a barometer, from the Greekbaros, meaning "weight," because it literally measures the weight of the atmosphere. Repeated experiments showed that the average pressure of the atmosphere at sea level is equal to the pressure of a column of mercury 760 mm tall. Thus, a standard unit of pressure known as the atmosphere was defined as follows. 1 atm = 760 mmHg To recognize Torricelli's contributions, some scientists describe pressure in units of "torr," which are defined as follows. 1 torr = 1 mmHg Although chemists still work with pressures in units of atm or mmHg, neither unit is accepted in the SI system. The SI unit of pressure is the pascal (Pa). The relationship between one standard atmosphere pressure and the pascal is given by the following equalities. 1 atm = 101,325 Pa = 101.325 kPa On the AP exam pressure units are generally given in atm or mmHg. However, you must know and be able to use all of the units in this course. HOMEWORK: Gas law packet & practice exercises 10.1-10.3