Catrina Turner paper 2014 - eCommons@Cornell

advertisement

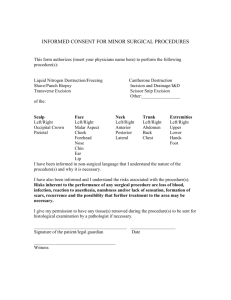

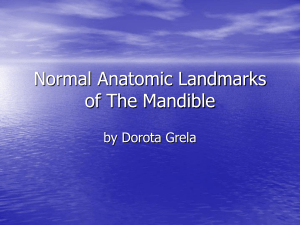

Mandibular Rim Excision as Treatment for Canine Acanthomatous Ameloblastoma Catrina Turner Clinical Advisor: Dr. Santiago Peralta Basic Science Advisor: Dr. John Hermanson Senior Seminar Paper Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine April 16th, 2014 1 ABSTRACT A 6 -year-old female spayed golden retriever was presented to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals Oncology Service as a referral for recurrence of an oral mass post marginal resection. Physical exam revealed a 1.5-cm in diameter, raised mass with irregular margins on the buccal aspect of the caudal left mandible. Results of fine needle aspirate of the mass were suggestive of ameloblastic fibroma. Diagnostic workup included: complete blood count, chemistry panel, urinalysis, 3-view thoracic radiographs, computed tomographic (CT) scan and intraoral radiographs. The latter two procedures showed a small amount of bony lysis associated with the mass. Mandibular rim excision was performed without complication. Histological analysis confirmed acanthomatous ameloblastoma with clean surgical margins. This paper will use a case-based format to discuss acanthomatous ameloblastoma, its corresponding differential diagnosis and the indications and implications of mandibular rim excision as compared to other types of mandibulectomy. 2 INTRODUCTION Canine Acanthomatous Ameloblastma (CAA) is a benign odontogenic tumor. It is locally invasive, causing bone lysis and often displacing teeth.1, 2 It is generally accepted that for malignant and benign but locally invasive oral tumors surgical excision with wide margins is indicated. Partial to full mandibulectomy has traditionally been utilized in most of these cases to obtain adequate margins. Another surgical technique known as mandibular “rim excision” or alveolar ridge resection has been reported as another potential surgical option for treatment of these masses. This procedure removes the dorsal portion of the mandible and involved dentition while leaving the ventral cortex intact.1, 3, 4 CASE STUDY History A six-year-old spayed female golden retriever was presented to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals’ (CUHA) Oncology Service in March 2013 as a referral case from a general practitioner for an oral mass. In February of 2013 the patients owners noticed a quarter size oral mass on the buccal aspect of her left mandible. The mass was marginally excised using electrocautery by their primary care veterinarian in early March 2013. Histological analysis of a biopsy obtained at the time of surgery revealed acanthomatous ameloblastoma. Approximately two weeks after excision the patient’s owners noticed a dime-sized mass at the same location, indicating local recurrence. At that point the dog was referred for further diagnostic workup and possible treatment. 3 Physical Exam On presentation the patient was bright, alert, and responsive. Vital parameters were within normal limits. The dog weighed 29.7kg and was in good body condition with a body condition score of 5/9. On physical exam a 1.5-cm in diameter, raised mass with irregular margins, was seen on the buccal aspect of the caudal left mandible and moderate medial buttress of her left stifle was palpated. Otherwise her physical exam was unremarkable. Differential Diagnosis Differential diagnosis for oral masses can be grouped as malignant or benign. Malignant oral masses include melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and lymphoma. The most common benign canine oral masses are acanthomatous ameloblastoma, odontoma, and peripheral odontogenic fibroma. 2, 4, 5 Diagnostics Initial diagnostic staging included: fine needle aspirate of the mass for histologic evaluation, complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry panel, and urinalysis on free catch urine, and three view thoracic radiographs. Results of the histologic evaluation suggested an ameloblastic fibroma as there was roughly equal distribution of odontogenic epithelium and mesenchymal components seen. Results of the urinalysis and thoracic radiographs were normal. The CBC revealed a mild neutropenia of 2.6 thou/uL (2.7 – 9.4 thou/uL). The differential diagnosis for this neutropenia included: 4 decreased production secondary to a myeloproliferative disease or metastatic neoplasia, drug-induced (trimethoprim-sulfa, phenobarbital etc.), infectious causes (ehrlichiosis, parvovirus infection), due to increased consumption secondary to septicemia, hypoadrenocorticism, or due to normal variation. The chemistry panel showed a mild hyperbilirubinemia of 0.3mg/dL (0.0 to 0.2mg/dL). The differential diagnosis included prehepatic causes such as hemolytic anemia, intrahepatic causes (cholestasis, cholangitis/cholangiohepatits), extrahepatic causes (pancreatitis, cholelithiasis), or due to normal variation. As the patient had no clinical signs or other supporting blood-work changes associated with the neutropenia and hyperbilirubinemia these were deemed clinically insignificant and likely due to normal patient variation. The patient returned 9 days later for aspirates of both mandibular lymph nodes and full abdominal ultrasound to evaluate for signs of metastasis. A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the skull, and intraoral radiographs were performed with the patient under general anesthesia to obtain information for surgical planning. Findings of the abdominal ultrasound and lymph node aspirates were unremarkable. The CT scan revealed a small soft tissue mass in the caudal left mandible with minimal associated bone lysis. The intraoral radiographs confirmed there was a small amount of bone lysis associated with the mass. During recovery from anesthesia the patient regurgitated a small amount of fluid; the endotracheal tube was in place and no secondary complications were seen. 5 Treatment Complete surgical excision was recommended as the best treatment option. Two surgical techniques were feasible as the mass had only invaded the dorsal portion of the mandible and did not enter the mandibular canal: segmental mandibulectomy or mandibular rim excision. Risks and benefits of the procedures were discussed with the owners and surgical excision using the rim excision technique was elected. The patient returned 12 days later for surgery. Blood was collected for a CBC and chemistry panel; results were consistent with previously blood work. The dog was placed under general anesthesia and the pharynx was packed with gauze to prevent aspiration of any fluid during the procedure. To reduce the bacterial load in the mouth before the procedure supra- and subgingival ultrasonic scaling was performed and the mouth was rinsed with a 0.05% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse. The planned incision site was marked with a surgical pen approximating 15mm to 20mm margins from the surgical site, this included the left mandibular premolar 4 through the left mandibular molar 3. An inferior alveolar nerve block was performed in the left mandibular canal. The surgical field was created around the mouth with sterile towels. The mucosal incision was made using a #15 blade. The mucosa on the buccal aspect was further dissected using a P24G periosteal elevator. Osteotomy was performed using a piezoelectric oral surgery unit while irrigating with lactated Ringer’s solution. The osteotomy was successfully performed. The mandibular canal was exposed; the inferior alveolar artery and nerve were preserved. The left mandibular third molar tooth and root fragments of the left mandibular fourth premolar were luxated and extracted using 2mm and 3mm dental luxators and Cryer’s extraction forceps. The irregular bony edges of the 6 surgical site were reduced using rongeours. The area was copiously rinsed with sterile saline and a splash block directly over the inferior alveolar nerve was performed. New sterile drapes and instruments were used for closure. A one layer closure was performed in a simple interrupted pattern using 25 poliglecaprone. Postoperative radiographs were obtained confirming there were no tooth roots remaining. The patient recovered from anesthesia uneventfully and was administered a dose of carprofen at 1.1mg/kg subcutaneously during recovery. The dog was maintained on intravenous fluids and fentanyl at 2µg/kg/hr for pain. Overnight the patient was administered a 0.5mg/kg dose of dexmedetomidine and a 0.01mg/kg dose of acepromazine intravenously to decrease anxiety in the hospital. The dog was discharged the next morning with the following medications: tramadol (2.5mg/kg PO BID-TID), carprofen (1.6mg/kg PO BID), and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (17mg/kg PO BID). The owners were instructed to feed the dog only a soft-food gruel until the recheck appointment in 2 weeks and not allow rough play with other animals, with any toys or other hard objects until further notice. At the 2 week recheck the site was healing well, the sutures were still absorbing and there was minimal redness and swelling. Histological analysis of the surgical specimen confirmed acanthomatous ameloblastoma with clean surgical margins; 7mm margins deep and 3-5mm margins laterally were reported. Prognosis The prognosis for patients with complete surgical excision of CAA is considered excellent. If 1-cm margins are obtained the surgery is often considered curative. One 7 study reports 100% survival rate 1 year post wide surgical excision in 25 dogs. 7 Another study, using the mandibular rim excision technique in 7 dogs with CAA, had a follow-up time ranging from 3 month to 5 years and there was no evidence of tumor recurrence seen.1 DISCUSSION In domestic animals there are only 2 commonly occurring odontogenic tumors; CAA and peripheral odontogenic fibroma.2, 5 CAA has various names in the literature as it has changed through the years along with the advancement of research. Historically, CAA was referred to as acanthomatous epulis which was replaced by peripheral ameloblastoma and later changed to CAA.4 It is widely accepted that CAA arises from remnants of the odontogenic epithelium in the future tooth bearing regions of the gingiva. There are reports, however, that it is possible that CAA arises intraosseously and breaks out of the bone.4,6 What makes CAA different from other odontogenic tumors is that it tends to invade the underlying cancellous bone and has a high rate of recurrence after marginal resection.1,2,4 Clinically, it appears as a gingival mass usually having an irregular surface. It may be ulcerated and sometimes displaces surrounding teeth. It has been diagnosed in a wide age range of dogs but the mean age of occurrence is 7.5 to 10.5 years.2 In the dog there has been no reports of metastasis.1,4 Histologically CAA appears as islands and cords of squamous epithelium irregularly dispersed through a connective tissue stroma. Many basal cells are columnar and palisading, some having reverse nuclear polarization and cytoplasmic vacuolation.2, 4, 6 8 Due to its tendency to recur after marginal resection wide surgical excision is usually the recommended treatment option for CAA though radiation therapy is also sometimes used. Wide local excision has commonly been accomplished by used of a partial mandibulectomy or maxillectomy but in recent years the rim excision procedure has come into play as another potential treatment option.1,4 This procedure has been used in humans with oral neoplasms since 1987 with comparable success as segmental mandibulectomy.3 As previously discussed, this procedure removes the dorsal portion of the segment of the mandible containing the mass and the involved dentition, leaving the ventral cortex containing the mandibular canal intact. The mandibular canal contains the inferior alveolar artery, vein, and nerve, along with loose connective tissue, and fat. Preservation of these structures and the ventral cortex, which is the strongest portion of the bone does offer several benefits. It is important to point out that any tumor invasion of the mandibular canal would automatically eliminate the rim excision procedure as a treatment option.1, 3, 4 The most common postoperative complication seen with the segmental mandibulectomy is “mandibular drift” where the remaining rostral portion of the mandible on the affected side drifts medially causing a traumatic malocclusion. Here lies the main benefit of the rim excision procedure, due to the preservation of the ventral cortex this mandibular drift does not occur. Another benefit of the rim excision procedure is that there is a preservation in some jaw stability as the ventral cortex of the mandible is the strongest portion of the bone.1,3,4 Studies have shown that bony remodeling occurs in the mandibular defect eventually giving many patients a full return to normal function. 9 There is a risk of jaw fracture at the site, especially during the few months after surgery.3 REFERENCES: 1. Murray, R. L., Aitken, M. L., Gottfried, S. D. The Use of Rim Excision as a Treatment for Canine Acanthomatous Ameloblastoma. Journal of American Animal Hospital Association, 2010; 46:91-96 2. Gardner D.G. Canine acanthomatous epulis; The only common spontaneous ameloblastoma in animals. Oral surgery, Oral medicine, Oral pathology, 1995; 79: 612615 3. Arzi, B., Verstraete, F. Mandibular Rim Excision in Seven Dogs. Veterinary Surgery, 2010; 39: 226-231 4. Verstraete F., Lommer M. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in Dogs and Cats. Saunders publishing. 2012. 403-409, 467-478 5. Gardner D.G., An Orderly Approach to the Study of Odontogenic Tumours in Animals. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 1992; 107, 427-438 10 6. Garder D.G., Baker D.C. The relationship of canine acanthomatous epulis to ameloblastoma. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 1993; 108:47-55 7. White RA, Gorman NT. Wide local excision of acanthomatous epulides in the dog. Veterinary Surgery, 1989; 12-14 11