Stapleton and Lowry: Two New Neighborhoods Take Flight

advertisement

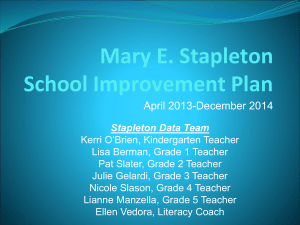

Stapleton and Lowry: Two New Neighborhoods Take Flight A history of aviation and adaptive reuse has generated two unique developments in Denver By Mary Voelz Chandler When voters in the late 1980s approved construction of a new Denver airport northeast of the city, city planners began to figure out what to do with the land at Stapleton International Airport. Close to the city, but surrounded by homes (and noise-weary neighbors), Stapleton became the subject of intense study, eventually turning the area into a planned, New Urbanist community. Then, a year before Stapleton International Airport closed in 1995, the Lowry Air Force Base to the south ceased operation. Announced in 1991, Lowry’s closure left another giant parcel–3.3 square miles of land, numerous buildings, and three runways–also open for New Urbanist redevelopment. This sudden availability of land presented the delicate balance of opportunities and challenges, urbanism and suburbanism. It also lured people eager to live in places convenient to downtown Denver, but in planned neighborhoods that avoided the “messy” side of city living. Two decades later, Stapleton and Lowry have taken different tacks in facing the future while honoring the past. While Lowry has preserved numerous former base structures as repurposed, living landmarks, Stapleton has found new uses for some buildings, all of which visitors to the 2013 AIA Convention in Denver will have the opportunity visit. Stapleton Forest City Stapleton was selected as the master developer, selling off parcels to home builders who were required to follow design guidelines found in a weighty document called the Green Book. The 4,100-plus-acre megaproject has evolved into what in effect is a new mini-town on the eastern edge of the city. The Green Book focused on several home styles prevalent in Denver; traditional designs with alley loaded garages that fill the sections developed early in the planning process. Recent developments have become more contemporary in vision, though the truly distinctive projects in Stapleton tend toward public buildings and a commercial center. In turn, people have flocked to Stapleton to live, work, and play. Stapleton is a magnet for families drawn to the new schools and recreational opportunities provided by Central Park, playgrounds, trails, and a recreation center, as well as commercial and office clusters. A demographic study conducted by the Piton Foundation and drawn from 2010 census figures showed that about 75 percent of Denver’s recent growth has happened in Stapleton and areas farther to the northeast. And more growth is on the way, in the form of hundreds of homes in an area with an eco-boost. “We do our best to anticipate the direction of the market and be innovating demand while remaining true to urban design,” says longtime Forest City Stapleton spokesperson Thomas J. Glean. “Our newest neighborhood, Conservatory Green, is a more organic expression of the principles that have made Stapleton known for its quality of life, while celebrating the relaxed nature of the landscape. Special accommodations for home gardens and [an] edible landscape in public spaces have already generated a lot of excitement.” Examples of distinctive buildings include: 29th Avenue Town Center, 7351 E. 29th Ave., 4240 Architecture, 2004: This sensitively designed mix of retail, office and residential developments serves as a gateway and main street for Stapleton. The narrow streets, ample sidewalks, diverse storefronts, and cozy feel are bolstered by contemporary architecture, a nearby park, and the 2012 LEED Gold Sam Gary Branch Library, designed by OZ Architecture. Anchor Center for the Blind, 2550 Roslyn St., Davis Partnership Architects, 2007: The center appears playful on the exterior, with its different planes, levels, and rambling spaces. But that sense of fun evolves inside into spaces for serious learning and a tool for instruction. Designed to serve children with vision impairments, the center incorporates light and color to promote a sense of normalcy and joy, including spaces that appeal to the development of other senses. Denver School of Science and Technology, 2000 Valentia St., klipp architecture, 2004: klipp’s design for the public charter Denver School of Science and Technology proves that industrial elements, geometric forms, and a diverse color palette can add a sexy aura to a technology-focused academic emphasis. The serious nature of the school’s mission is reflected in architectural elements that combine to make a forward-looking building that is LEED Silver certified. Hangar 61, 8695 Montview Blvd., Fisher and Fisher and Davis, with engineer Milo Ketchum, 1959; adaptive reuse in 2009: This rare surviving example of thin-shell concrete construction and engineering features a diamond-shaped domed roof balanced and supported by two immense concrete buttresses. Preservationists and historians worried in 2004 that the expansion of Stapleton would be the end of a building that had stood empty for years. But a concerted community effort and brave developer took on the work: repairing loose concrete, diging out a tree that had grown in the cracked dome, fixing the buttresses that hold down the roof, and upgrading all building systems. The hangar’s unusual sleek form and strong historical ties contribute the flair of air travel to a development that can appear more generic than rooted in a specific place. Hangar 61 also demonstrates that adaptive reuse can happen anywhere, if given a chance. The building now houses the Stapleton Fellowship Church. FBI Denver Field Office, 8000 E. 36th Ave., SOM, with Anderson Mason Dale Architects, 2010: In a development where the glitz factor is low, it’s a surprise to round a corner and suddenly see this shimmering cube. The fence around this four-story FBI field office says high security. But the curtainwall –strips of iridescent glass tinged with blue and green–indicates the sense of openness and light inside. Central Park Recreation Center, 9651 E. Martin Luther King Blvd., Sink Combs Dethlefs, 2011: Clean lines and a prominent location make this LEED GOLD certified building stand out as a hub for recreational pursuits. Its contemporary design relies on a mix of intelligent proportions and a welcoming white-columned entry. Lowry The Lowry Redevelopment Authority (LRA) was formed in 1991 and set a course that included new, low-key residential, retail, office, educational spaces, and parks. But Lowry also included impressive existing buildings, saved to play off a military theme in terms of aesthetics and branding. “The historic buildings here were a huge asset,” says Hilarie Portell, founder of the community marketing firm Portell Works and a spokesperson for the development. “Lowry was a fully functioning community for years. It had a nice small town feel to it.” Drawing up districts and finding creative reuses for buildings were key, she says. “The old base liquor store is now a community church, and the steam plant is a loft development.” Two historic districts exist in Lowry: The Officers’ Row Historic District and the Lowry Technical Training Center Historic District. More growth is coming to Lowry, too, with redevelopment of the 1970s Buckley Annex area. It’s the last parcel to be transferred to the LRA when the annex ceased operation and was vacated in 2011. Officers Row Loft Homes, Roslyn Street from East 1st to East 4th avenues, Christopher Carvell Architects, 2000: This new development sits to the west of the historic old barracks, bringing a contemporary flair that works well with the structure that became base headquarters in the 1960s. Steam Plant Lofts, East 4th Avenue and Red Cross Way, circa 1940, redevelopment by Hartman Ely Investments, Jim Hartman, Architect and Development Manager, 2006: This massive building with its four shiny cone-like chimneys created heat for dozens of buildings on the Lowry base. It was redeveloped into lofts, with the addition nearby of a town home complex. Schlessman Family Branch Library, 100 Poplar St., Brendle APV, 2002: Although it’s across Quebec Street from Lowry, architect Michael Brendle’s angular library features a design with significant sections clad in matte aluminum that plays up the concept of flight. Canted geometric forms give the library a sculptural presence. Hangar No. 1/Wings Over the Rockies Museum and Hanger No. 2, 7731 E. Academy Blvd., 1940 : It’s not hard to spot Hangar No. 1, and not just because it is a gigantic metal hangar. There is also a B-52 on the edge of its parking lot-part of the Wings Over the Rockies Museum, which helps keep Lowry’s history of aviation alive. Several years ago, museum officials caused a stir by proposing that the adjacent Hangar No. 2 be torn down and the land sold to save money on maintenance. Instead, Hangar No. 2 is now home to a storage facility, with retail and a developing dining center. The Eisenhower Chapel, 293 Roslyn St., 1941: This small chapel with the lines of a prairie church earned its name because President Eisenhower and his wife Mamie worshipped there when he spent time in Denver. It is located to the east of Lowry’s Town Center. Denver resident Mary Voelz Chandler has written about architecture, preservation, art, and design for more than 20 years. She is the author of the Guide to Denver Architecture and was formerly the architecture writer at the Rocky Mountain News. She was also a writer at Fentress Architects, where she completed two books on the firm’s work, and is currently a business development communications specialist at GH Phipps Construction Companies. Chandler received the AIA Colorado 2005 award for Contribution to the Built Environment by a Non-Architect, and was honored by the Denver Art Museum in 2012 with the DAM Contemporaries DAMKey Award. Recent Related: Denver’s Central Platte Valley: A Dynamic Decade Civic Center: Denver’s Civic and Cultural Heart Modernist Ideals Thrive in Suburban Denver Reference: Visit the AIA Convention Website. Back to AIArchitect May 24, 2013 Go to the current issue of AIArchitect