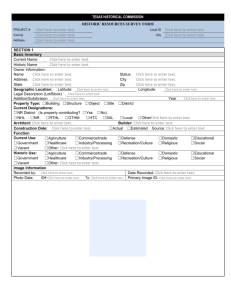

historic cultural property inventory form

advertisement