Enthymemes as a Pedagogical Tool to Teach Audience Persuasion

advertisement

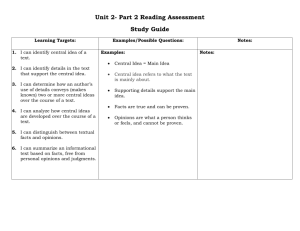

Enthymemes as a Pedagogical Tool to Teach Audience Persuasion Writing enthymemes trains students to focus on audience reception BECAUSE The enthymeme makes explicit audience assumptions and determines compositional structure. Emmel, Green and Gage each discuss the advantage of teaching enthymemes in the classroom. Emmel explains that writing enthymemes trains students to focus on audience reception. Teaching students to use the classroom to share, discuss and challenge ideas, and ultimately reach an agreement on conclusions, illustrates how communication structure impacts the effectiveness of an argument (Emmel, p. 133). Enthymemes are seen ubiquitously where forms of reasoning occurs, regardless of our awareness, in social situations and in media, as enthymemic reasoning pervades discourse and shapes our thinking (Green, p. 623). Enthymemic assertions used by a student are determined by his assessment of his audience understanding and receptivity, which allows him to incorporate terms shaped through collabortion into the final argument (Gage, p. 40). Through discourse, students discover common topics for which they can build the foundations of an argument. Discussing, debating and sharing ideas with an audience leads to the discovery of common ground and clarity on the topics argued within an enthymeme. Each aspect of the enthymeme formation, from the mental processes to word choice in expression, is affected by discussions between a student and his peers, and helps form the enthymeme, which bridges the problem with the earned conclusion (Gage, 42). When conflict arises regarding agreement on an assertion’s validity, a polar belief can only be penetrated and swayed through the use of examples or paradigms that prove otherwise (Green, 629). Careful word selection assists in shaping claims that are initially rejected by an audience, and unpacking terms can help draw out mutually agreed upon terms (Emmel, 139). Discourse aids in assessing the areas the audience agrees with the terms of the student’s argument, allowing him to offer paradigms in support of his argument. Compositional structure is influenced by the audience’s beliefs pertaining to the argument, as the framework of an enthymemic argument is dependent on terms supported by both writer and audience. Using transitive verbs in an enthymeme lends influence to an argument as such verbs of consequence aid in supporting implicit premises (Green, 630). Enthymemes are based on sharing, testing and challenging ideas, which lead to more logical arguments than most formula-based theses, hence it is advantageous to structure an argument around an enthymeme (Gage, 38). Knowing your audience lets you gauge what can be left implied and what must be explained when structuring commission, putting value in defining and refining terms (Emmel, 136). The use of transitive verbs, as well as re-evaluating terms, lends support to the claims of the enthymeme by tailoring them to offer more implicit arguments. Classroom discussion allows for the discovery of common topics between a student and his peers, who serve as an audience. Once discrepancies have been determined, a student can use paradigm to support his assertion to his peers. The structure of the argument is molded by through reworking definition to adjust to audience cognition, which in turn affects the form of the enthymeme. Writing enthymemes trains students to focus on audience reception because the enthymeme makes explicit audience assumptions, and determines compositional structure. References Lawrence D. Green (Feb., 1980) Enthymemic Invention and Structural Prediction College English, College English, Vol. 41, No. 6, pp. 623-634 Published by: National Council of Teachers of English John T. Gage (Sept.1983) Teaching the Enthymeme: Invention and Arrangement. Rhetoric Review. Vol. 2, No. 1 , pp. 38-50 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Emmel, B. A. (1994). Toward a Pedagogy of the Enthymeme: The Roles of Dialogue, Intention, and Function in Shaping Argument Rhetoric Review, 13(1), 132-149.