The Protestant Reformation In the year 1520, every church in

advertisement

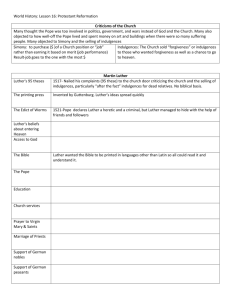

The Protestant Reformation In the year 1520, every church in western Europe was a Roman Catholic church, a fact which had not changed since the dawn of Christendom. Yet by 1540, the picture was much different because now people of several new Christian denominations could be found worshipping in many of these same churches. In a short period of time, a religious revolution called the Protestant Reformation had taken place, and as a result, nearly 16 centuries of unbroken Catholic domination of Christianity ended in western Europe….what led to this rebellion against what was then the wealthiest and most powerful institution on earth? Early in the 14th century, several important events occurred which later caused serious problems for the Church. The first happened in 1302, the year that the pope issued a formal decree stating that salvation was not possible outside the Roman Catholic Church, and that ultimate truth and power, both religious and political, came only from the pope. The second happened seven years later when turmoil within the Church caused its capital to be moved from the city of Rome, where it had been located for nearly 13 centuries, to the southern French town of Avignon. At Avignon a magnificent new papal palace was constructed. It rose high above the rest of the town symbolizing the enormous power of the papacy. The palace soon filled up with fantastic treasures that were crafted from gold and ornamented with precious jewels. But, as beautiful as these objects were, an over-fondness for riches led to corruption at the papal court, for so great was their wealth and love of luxury, that people were very disturbed by it. Then in 1337, as the pope's palace at Avignon continued to grow in size and splendor, a violent war erupted between France and England, a war that would last for over a century; while just one decade later, in 1347, a massive outbreak of the Black Plague brought death to 25 million Europeans in just four years’ time. To the horrible problems of war and plague, the church added a third problem of its own, when factions in Rome elected a second pope; so for the next 31 years, popes at Avignon and Rome battled for control of the Church. To make matters even worse, a third man was elected pope, so that from 1409-1415 three men struggled for power. Eventually the Church resolved this situation, but by now tremendous damage had been done to its prestige. Many ordinary Christians didn't know who to believe anymore. They mistrusted their religious leaders, for in them truth and goodness seemed to have been replaced by arrogance and corruption. To these believers it seemed that the simple teachings of Christ had been abandoned and that the Church was in desperate need of reform. Yet at this time people who spoke out about changing the ways of the Church could be put on trial and, if found guilty, burned at the stake for heresy. That was the fate of early Protestant reformer Johannes Hus in Czechoslovakia, and of a monk named Savonarola, who was publically executed 500 years ago in the central square of Florence for denouncing the immorality and corruption of the Renaissance popes. But one man, Martin Luther (1483-1546), was able to escape the unfortunate fate of some of these earlier reformers and, because of his strong beliefs, both the religious and the political character of western Europe were changed forever. Martin Luther was born in northern Germany in 1483, and as a youth he lived for several years in…town of Eisenach while he attended the nearby church school. This must have been a fascinating time to have attended school since people were just beginning to talk about the recent discoveries of Christopher Columbus. And this was also the time that, thanks to the invention of a new kind of printing press, the mass production of books was allowing information and ideas to spread rapidly for the very first time. In 1501, after finishing his early schooling, Luther moved east to the great cathedral city of Erfurt…where at first he attended its university, and then later began to live at [a] monastery after joining its community of hermit monks. And although the religious life he was required to follow here was very difficult, it seemed to suit him quite well, for a short time later he was ordained a Catholic priest. After leaving the monastery, Luther went to the University at Wittenberg, and it was here that he was to spend most of his life working as a professor of theology teaching biblical scripture. And it was also in the town of Wittenberg where the first step was taken that was to lead directly to the Protestant Reformation. On October 31, 1517, Luther arrived outside the doors of the castle church to post a list of 95 criticisms he had compiled protesting the Church practice of selling indulgences. An indulgence is a spiritual favor granted by the Church to sinners. The Church teaches that through indulgences, the punishments for sins that have already been forgiven by a priest are eliminated, thereby removing obstacles on the path to heaven. In the early days of the Church, indulgences could only be obtained by making difficult spiritual sacrifices, such as going on a pilgrimage to a holy shrine. Unfortunately, by Luther's time, the original, purely spiritual, intention of indulgences had become corrupted, for now indulgences were an important source of income for the Church and could be purchased for cash just like any other commodity, with no need for any spiritual sacrifice at all. And it was this practice of turning something spiritual into a mere business transaction that brought Luther's condemnation at the church of Wittenberg Castle. Then a short time later, Luther publicly criticized other Church practices as well. As a consequence, he was visited by the pope's emissary, who attempted to stop him from stirring up trouble for the Church. But Luther's response was to say that he had no faith in the pope and trusted in the Bible alone; that he had searched its pages carefully and could find nothing that supported either the sale of indulgences or the pope's infallibility. And when the pope sent a letter commanding his obedience, he simply hurled it onto a bonfire. Luther stubbornly refused to yield and soon published three revolutionary books that were critical of the Church, and even though their sale was officially forbidden, these writings were openly sold all across Germany. Finally, on January 3rd of 1521, Luther was banished from the Church, but his troubles did not end there. The secular ruler of the German States, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sought to punish Luther even further, for the emperor was a strong supporter of the pope. Charles summoned his representatives from their castles in the farflung states that made up his vast empire ordering them to come to the German city of Worms. And in a palace next to this great cathedral, the emperor and his representatives met in a formal assembly called the "Imperial Diet," now known as the "Diet of Worms." [There] on April 17th and 18th of 1521, Martin Luther, accompanied byhis lawyer, was told that he must recant, that is take back, his unacceptable religious views. He replied that it was impossible for him to go against what his conscience told him was right. The next day the disgusted emperor informed the gathering that he was ready to take actions against Luther for being a "a notorious heretic." Yet while the Diet deliberated his fate inside the palace, Luther remained a free man. It was during this time that a powerful German lord named Fredrick the Wise, who was a strong supporter of Luther, arranged to have him "kidnapped" and taken to [Fredrick’s] castle for his own protection. And while at the castle, Luther wore a disguise and his identity was kept a closely guarded secret. During this time of hiding, Luther immediately set to work translating the Bible into German, something that had never been done before. Then, three weeks after Luther had disappeared from view, "The Edict of Worms," seen here, was posted all across Germany. It told what should be done with the fugitive and his supporters. It commanded the emperor’s subjects to crush them,... to capture them and take their properties,... unless they had mended their errors and been absolved by the pope. In Germany the popular response to the "Edict of Worms" was to become a great turning point in the history of western civilization because most people simply chose to ignore it. And as a result, it was not long before Lutheranism was adopted as the official religion in many of the German states. In certain ways Lutheranism was a reformulation of old Christian beliefs and practices freed from papal control, but wherever the new religion was adopted, significant political changes followed. For example, rulers who adopted Lutheranism often used it as a way to enhance their own authority at the expense of the pope and to keep more money for themselves instead of having to send it off to Rome. German peasants, feeling a new sense of freedom, used it as an excuse to revolt against their rulers, but in 1525, after Luther refused to support their cause because of the political chaos it was creating, 100,000 peasants died trying to improve their impoverished lives. In the 1500 years from the birth of Christ up to the lifetime of Martin Luther, only one major break had ever developed within the Christian faith. This occurred in the Fifth Century A.D. when Christians in Greece split from Roman control and formed the Eastern Orthodox Church. But this church never gained a foothold in western Europe, which remained purely Catholic. In contrast, in the sixteenth century after Luther started his Church, many new, non-Catholic, Christian denominations formed in just a few decades. For example, in 1522 the theologian Ulrich Zwingli, seen here, convinced the leaders of the Swiss city of Zurich that churches should be freed from papal control and that all religious images should be removed because their use smacked of pagan idolatry and that a simplified prayer service should replace the Catholic Mass. A short time later, this French theologian named John Calvin inspired an even larger number of Swiss citizens to join the Protestant movement. Calvin shared many of Luther's beliefs, but he expanded on them by preaching his grim doctrine called Predestination. Predestination means that even before the time of birth, God knows whether a person will go to heaven or to hell, and that even if someone leads a life that is free from sin, they might still be doomed. This, Calvin said, was an example of the "terrible majesty of God." But even in spite of this fatalistic doctrine, each Calvinist was still expected to lead a moral life–to work hard and to be thrifty. And by fostering these virtues, capitalism came to flourish in countries where Calvinist ideas took hold. In the Swiss city of Geneva, Calvinists formed a special police force to maintain public morality. Punishments were administered for adultery, swearing, drunkeness, wearing lavish clothing, laughing in church, and for overcharging customers. And the Calvinists continued the old Catholic tradition of burning heretics at the stake–a fate that also awaited anyone found to be practicing witchcraft. The Protestant Reformation in England happened for quite different reasons than it did in Switzerland and Germany. In England, the break with the Church occurred not for theological reasons, but because the king refused to accept a papal decision. The English king, Henry VIII, wanted a new wife. But since Catholicism forbids divorce, Henry had to ask the pope to grant him an annulment—a decree stating that his existing marriage had never been valid. But the pope refused, and when word of this reached the royal castle, Henry became so enraged that he decided to abolish papal authority. And in 1534, through the Act Of Supremacy, he declared himself to be the supreme head of the Church in England, divorced his wife, and went on to marry five more times. It seems likely that Henry also severed his ties to Rome because the Church kept demanding more and more money from him, even though the Catholic monasteries already controlled one-third of the arable farm land in his kingdom. Henry desperately wanted control of that land, so in 1536 he decided that all English monasteries should be abolished. He ordered the monks to leave, declared that anything of value now belonged to him, had the roofs taken off the buildings, and then let them fall into ruin. And by 1539, every one of England's over 500 monasteries was gone. Thus, through the "Dissolution of the Monasteries," the king increased his wealth enormously, and by handing over some of this property to his aristocratic friends, he was able to greatly strengthen his political support throughout the kingdom. Oddly enough, unlike Luther and Calvin, Henry had no real problem with the basic teachings of the Church, he just hated being subservient to the pope. Consequently, the services and sacraments of the Church of England differed very little from traditional Catholic practices. It was not until after King Henry's death that more radical religious changes were introduced.These included the adoption of both the Book of Common Prayer and Sacraments and of 42 articles of faith that spelled out the beliefs of the Church of England. In …the northern Italian city of Trento, a great council of the Catholic Church met between the years 1545 and 1563 to try to work out a solution to the growing Protestant rebellion. The final decision reached by this council, called the COUNCIL OF TRENT, was that the Church would yield nothing to the religious rebels. Instead, all of the traditional teachings of the Church were upheld. The council reaffirmed that in addition to the Bible, the pope and church councils are also a valid source of religious truth; that performing good works can help win salvation, which neither Calvin nor Luther believed; that indulgences can reduce a sinner's time in purgatory; that there are seven holy sacraments, not just the two recognized by Luther; that marriage cannot be dissolved; and that men who take the vows of priests must never marry. The Council also acted decisively to reform abuses within the Church hierarchy, to reinstate a more active religious role for bishops, and to increase the educational functions of the Church as well as its role in caring for the sick and the poor. War was declared against all Protestant doctrines. The Catholic Church decided to use the full force of its ancient mystical tradition against the Protestant rebels. The contrast was great, for at the very same time the pope's lavish new church, St. Peter’s Basilica, was going up in Rome, Calvinists to the north were worshipping in barren, austere spaces, having destroyed all the religious statues and stained glass they once contained. And by the end of the 1500s, such antagonism had developed between Catholics and Protestants that early in the next century it would erupt into 30 years of full-blown warfare. Source: Ancient Lights. The Protestant Reformation (1517-1565). From Discovery Education. Full Video. 1997. http://www.discoveryeducation.com/ (accessed 25 September 2012).