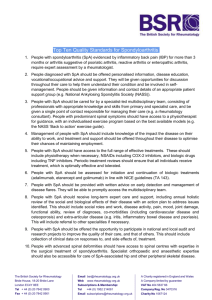

Paediatric rheumatology - The British Society for Rheumatology

advertisement

MCQs in Rheumatology: Paediatric rheumatology Contributors: These MCQs were written by Dr Anne-Marie McMahon, and Dr Daniel Hawley, Consultant Paediatric Rheumatologists at Sheffield Children’s Hospital. www.rheumatology.org.uk/education Question 1 A 2-year-old boy presents with a 7-week history of fever, with daily spikes of 40°C, a pink rash that comes and goes with the temperature. He has had swelling of both wrists, both elbows, both knees and both ankles for 7 weeks. He has generalized lymphadenopathy, and a palpable spleen 1cm. Investigations show Hb 7.5 gm/dl, WCC 2.2 x 103/ml, platelets 106 x 105/ml, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 118mm/hr and C reactive protein 24 mg/l. Antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, and rheumatoid factor are negative. Which of the following is the most important investigation for this child? 1. Blood film 2. Bone marrow aspirate 3. Ferritin 4. Anti-CCP antibodies 5. Cardiac ECHO Question 2 A 6 year old boy has a 2 month history of left knee swelling. This has been persistent and associated with 30 minutes of stiffness each morning. The child is otherwise well without features of weight loss, lethargy, skin changes or fever. There is no history of preceding trauma. The child’s General Practitioner prescribed a non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) early in the course of symptoms. The family feel this did not help. Which of the following is the most important treatment for this child? 1. A trial of an alternative NSAID 2. 3-days of intravenous steroid infusions 3. Intra-articular steroid injection to the left knee 4. Sub-cutaneous methotrexate 5. Oral methotrexate www.rheumatology.org.uk/education Question 3 A 2 year old boy develops a widespread purpuric rash, most prominent over the legs and buttocks. Although initially treated with 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics for meningococcal sepsis, no evidence for infection is subsequently found and this diagnosis is discounted. The child remains afebrile and well, but develops swelling of the knees and ankles and becomes reluctant to weight-bear. Urinalysis persistently shows mild proteinuria. Blood pressure and serum urea and electrolytes are normal. After 5 days in hospital the child is discharged home. Which of the following is the most important follow-up investigation for this child? 1. Ultrasound scans of the affected joints 2. A skin biopsy 3. Regular urinalysis and blood pressure monitoring 4. A 24 hour urine collection for protein/creatinine ratio 5. Regular joint assessment by a rheumatologist Question 4 A 14 year old Caucasian girl presents with a 3 month history of swollen joints with early morning stiffness lasting 2 hours every day. She has not had temperatures, rash or weight loss. Her father has insulin dependent diabetes and a maternal grandmother has hypothyroidism. She is pale, thin and has swollen ankles, knees, elbows and wrists, and several swollen PIP joints. She has fixed flexion of both elbows, both knees, and reduced movement of his neck and wrists. There is no lymphadenopathy. No hepato-splenomegaly. Investigations show Hb 13.4 gm/dl; WCC 17 x 103/ml; Platelets 612 x105/ml; CRP 30 mg/dl; ESR 58 mm/hr; ANA negative. RF strongly positive. Before referral to you, the GP has placed her on oral Prednisolone 10mg once daily. Which of the following is the next treatment for this patient? 1. Subcutaneous Methotrexate 10-15mg/m2 weekly 2. Azathioprine 2mg/kg once daily 3. Etanercept 50mg once weekly 4. Infliximab 6mg/kg 5. Rituximab therapy www.rheumatology.org.uk/education Question 5 A 3 year old boy has a 3 month history of left knee swelling. This has been persistent and associated with 60 minutes of stiffness each morning. The child is otherwise well without features of weight loss, lethargy, skin changes or fever. You arrange an intraarticular injection of steroid for his left knee under general anaesthetic, and ask his GP to prescribe regular ibuprofen. The most important specialist to refer him to from your initial clinic visit is 1. Orthotics department 2. Dental team 3. Orthopaedics 4. Ophthalmology 5. General Paediatricians www.rheumatology.org.uk/education Answers Q1. 3. Bone marrow aspirate This scenario describes the classical presentation of a child with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The blood count shows pancytopenia. Pancytopenia in a child with arthritis must be investigated with a definitive bone marrow aspirate. Children with leukaemia can present with all the symptoms and signs of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis can develop the fatal complication of macrophage activation syndrome which manifests as pancytopenia associated with coagulopathy, liver dysfunction, hyperferritaemia and high triglycerides. A bone marrow aspirate is definitive for diagnosis in either case. Patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis should be referred to their local paediatric rheumatology centre. Q2. 3. Intra-articular steroid injection to the left knee This scenario describes the classical presentation of a child with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Initial treatment for this subtype includes trial of a NSAID and early recourse (certainly not delayed beyond 2 months) to intra-articular corticosteroid injection. Corticosteroid joint injections should be performed with triamcinolone hexacetonide, which has been shown to provide a relatively long duration of action. Intravenous steroid treatment is usually reserved for children with polyarticular disease not amenable to steroid joint injection (eg. neck involvement). Methotrexate may be appropriate in treating oligoarticular disease, but should be reserved for those requiring frequent joint injections or developing extended joint involvement. Q3. 3. Regular urinalysis and blood pressure monitoring The likely diagnosis for this child is Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP). This is the commonest form of vasculitis occurring in the paediatric population (annual incidence 20 per 100,000). Whilst often termed ‘benign’, HSP is associated with long-term renal compromise (including end-stage renal failure) in a minority. If significant renal involvement is going to occur it usually does so within the first year following an acute episode of HSP. For this reason, regular urinalysis and blood pressure monitoring is essential during this time to identify children who go on to develop serious renal involvement. Q4. 1. Subcutaneous Methotrexate 10-15mg/m2 weekly This scenario describes the classical presentation of a child with Rheumatoid Factor positive polyarthritis juvenile idiopathic arthritis. It is likely this patient will require intravenous Methylprednisolone and/or intra-articular joint injections in the initial induction of remission phase. However, definitive treatment with the correct dose of subcutaneous methotrexate commencing as soon as possible will allow control of inflammation to continue. Etanercept will be the next considerations for future therapy if methotrexate fails, after 3-4 months. Rituximab may be indicated if other biologic therapy fails. www.rheumatology.org.uk/education Q5. 4. Ophthalmology Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is associated with uveitis, a silent inflammation of the eye that may cause blindness if not appropriately screened for in patients with JIA. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology have guidelines issued in 2006, that state all patients with JIA (regardless of ANA status) must be screened 4 monthly in the first 2 years of disease, and for 5 years in total, or up to their 11 th birthday. There may be more frequent follow up for those with uveitis. It is the first uveitis screen that is important and this should be organized promptly from the diagnosis of JIA. www.rheumatology.org.uk/education