File - World History with Ms. Dalton

advertisement

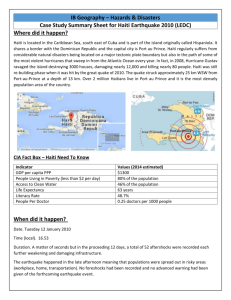

Going Beyond the Textbook The Haitian Revolution What the Textbook says: (Pg. 624) Analysis Questions: 1. Why was the Haitian Revolution unique? 2. Describe the location of Haiti 3. What European power controlled Haiti? 4. What caused the Haitian Revolution? 5. What “caste” led the revolution? 6. What single person led the revolution? a. What caste did he belong to? b. What did he do after the revolution? c. Through the French were the main perpetrators, what other European powers did he defeat? d. What was his fate? 7. What was the role of Napoleon in the revolution? 8. Why was Haitian independence unique? Now, let’s go BEYOND!... Haiti: a long descent to hell Haiti, born of slavery and revolution, has struggled with centuries of crippling debt, exploitation, corruption and violence Jon Henley Thursday 14 January 2010 14.00 EST Last modified on Wednesday 11 June 2014 14.11 EDT http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jan/14/haiti-history-earthquake-disaster (Pre-Reading) Analysis Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. Where did the article come from? Describe the source. What type of article is this? What is significant about the date of the article? How do you feel about the article title? Why? Geography and bad luck are only partly to blame for Haiti's tragedy. There are, plainly, more propitious places for a country and its capital city to find themselves than straddling the major fault line between the North American and Caribbean tectonic plates. It's more than unfortunate to be positioned plumb on the region's principal hurricane track, meaning you would be hit, in the 2008 season alone, by a quartet of storms as deadly and destructive as Fay, Gustav, Hannah and Ike (between them, they killed 800 people, and devastated more than 70% of Haiti's agricultural land). Wretched, also, to have fallen victim to calamitous flooding in 2002, 2003 (twice), 2006 and 2007. But what has really left Haiti in such a state today, what makes the country a constant and heart-rending site of recurring catastrophe, is its history. In Haiti, the last five centuries have combined to produce a people so poor, an infrastructure so nonexistent and a state so hopelessly ineffectual that whatever natural disaster chooses to strike next, its impact on the population will be magnified many, many times over. Every single factor that international experts look for when trying to measure a nation's vulnerability to natural disasters is, in Haiti, at the very top of the scale. Countries, when it comes to dealing with disaster, do not get worse. "Haiti has had slavery, revolution, debt, deforestation, corruption, exploitation and violence," says Alex von Tunzelmann, a historian and writer currently working on a book about the country and its near neighbours, the Dominican Republic and Cuba. "Now it has poverty, illiteracy, overcrowding, no infrastructure, environmental disaster and large areas without the rule of law. And that was before the earthquake. It sounds a terrible cliche, but it really is a perfect storm. This is a catastrophe beyond our worst imagination." It needn't, though, have been like this. In the 18th century, under French rule, Haiti – then called Saint-Domingue – was the Pearl of the Antilles, one of the richest islands in France's empire (though 800,000-odd African slaves who produced that wealth saw precious little of it). In the 1780s, Haiti exported 60% of all the coffee and 40% of all the sugar consumed in Europe: more than all of Britain's West Indian colonies combined. It subsequently became the first independent nation in Latin America, and remains the world's oldest black republic and the second-oldest republic in the western hemisphere after the United States. So what went wrong? Pause for Analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. What European power controlled Haiti? What was its name under this European power? What were Haiti’s major exports? What “superlative does Haiti hold? Haiti, or rather the large island in the western Atlantic of which the present-day Republic of Haiti occupies the western part, was discovered by Christopher Columbus in December 1492. The native Taino people knew it as Ayiti, but Columbus claimed it for the Spanish crown and named it La Isla Española. As Spanish interest in the island faltered with the discovery of gold and silver elsewhere in Latin America, the early occupiers moved east, leaving the western part of Hispaniola free for English, Dutch and particularly French buccaneers. The French West India Company gradually assumed control of the colony, and by 1665 France had formally claimed it as Saint-Domingue. A treaty with Spain 30 years later saw Madrid cede the western third of the island to Paris. Pause for Analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. Who originally occupied Haiti? Who “discovered” Haiti? For what crown? What is the name of the entire island on which Haiti occupies the western half? How did power transfer in Haiti? Economically, French occupation was a runaway success. But Haiti's riches could only be exploited by importing up to 40,000 slaves a year. For nearly a decade in the late 18th century, Haiti accounted for more than one-third of the entire Atlantic slave trade. Conditions for these men and women were atrocious; the average life expectancy for a slave on Haiti was 21 years. Abuse was dreadful, and routine: "Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars?" wrote one former slave some time later. "Have they not forced them to eat excrement? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss?" Pause for Analysis 1. How did Europeans deal with the high demand for Haiti’s resources? Not surprisingly, the French Revolution in 1789 raised the tricky question of how exactly the Declaration of the Rights of Man might be said to apply both to Haiti's then sizeable population of free gens de couleur (generally the offspring of a white plantation owner and a black concubine) – and ultimately to the slaves themselves. The rebellion of SaintDomingue's slaves began on the northern plains in August 1791, but the uprising, ensuing bloody civil war and finally bitter and spectacularly brutal battle against Napoleon Bonaparte's forces was not over for another 12 years. As France became increasingly distracted by war with Britain, the French commander, the Vicomte de Rochambeau, was finally defeated in November 1803 (though not before he had hanged, drowned or burned and buried alive thousands of rebels). Haiti declared independence on 1 January 1804. Pause for Analysis 1. 2. 3. 4. What as the Declaration of the Rights of Man? How did the French Revolution inspire revolution in Haiti? What is Napoleon’s role in the Haitian Revolution? What social “caste” led the Haitian Revolution? As Stephen Keppel of the Economist Intelligence Unit puts it, Haiti's revolution may have brought it independence but it also "ended up destroying the country's infrastructure and most of its plantations. It wasn't the best of starts for a fledgling republic." Moreover, in exchange for diplomatic recognition from France, the new republic was forced to pay enormous reparations: some 150m francs, in gold. It was an immense sum, and even reduced by more than half in 1830, far more than Haiti could afford. "The long and the short of it is that Haiti was paying reparations to France from 1825 until 1947," says Von Tunzelmann. "To come up with the money, it took out huge loans from American, German and French banks, at exorbitant rates of interest. By 1900, Haiti was spending about 80% of its national budget on loan repayments. It completely wrecked their economy. By the time the original reparations and interest were paid off, the place was basically destitute and trapped in a spiral of debt. Plus, a succession of leaders had more or less given up on trying to resolve Haiti's problems, and started looting it instead." Pause for Analysis 1. How did the Haitian Revolution impact Haiti? (List two examples.) The closing decades, though, of the 19th century did at least mark a period of relative stability. Haitian culture flourished, an intelligentsia emerged, and the sugar and rum industries started to grow once more. But then in 1911 came another revolution, followed almost immediately by nearly 20 years of occupation by a US terrified that Haiti was about to default on its massive debts. The Great Depression devastated the country's exports. There were revolts and coups and dictatorships, and then, in 1957, came François "Papa Doc" Duvalier. Papa Doc's regime is widely seen as one of the most corrupt and repressive in modern history. He exploited Haiti's traditional belief in voodoo to establish a personal militia, the feared and hated Tonton Macoutes, said to be zombies that he had raised from the dead. During the 28 years in power of Papa Doc and his playboy son and heir, Jean-Claude Duvalier, or Baby Doc, the Tonton Macoutes and their henchmen killed between 30,00 and 60,000 Haitians, and raped, beat and tortured countless more. Until Baby Doc's eventual flight into exile in 1986, Duvalier père and fils alsomade themselves very rich indeed. Aid agencies and international creditors donated and lent millions for projects that were often abandoned before completion, or never even started. Generous multinational corporations earned lucrative contracts. According to Von Tunzelmann, the Duvaliers were at times embezzling up to 80% of Haiti's international aid, while the debts they signed up to accounted for 45% of what the country owed last year. And when Baby Doc finally fled, estimates of what he took with him run as high as $900m. It is hardly surprising then that Haiti isn't Switzerland. The Duvaliers' departure, as Keppel puts it, "left a void, and a broken and corrupt government. Democracy got off to a really bad start there. The Duvaliers may have bankrupted the government, they may been brutal, but they could keep control of the place. Since they went, Haiti has seen more coups, ousters and social unrest." The country is short on investment, and desperately short on most of the infrastructure and apparatus of a functioning modern state. For Keppel, while Haiti's problems undoubtedly began "a long way back, there have been periods when it could have set itself on a different track". It's the recent transition from dictatorship to democracy that is at the root of today's problems, he believes. "It's led to a situation where the population is continuing to grow, where poverty drives many of them to Port-au-Prince, and where Port-au-Prince, even at the best of times, doesn't have the infrastructure to cope with them. And then comes an earthquake of an unprecedented magnitude . . ." Pause for Analysis 1. What caused major political change for Haiti in 1911? 2. Describe the leadership of Papa Doc. Give two examples to support your claim. Von Tunzelmann isn't so sure. Haiti's descent began earlier than that, she believes. One reason why Haiti suffers more than its neighbours from natural disasters like hurricanes and flooding is its massive deforestation, under way in the country since the time of the French occupation, she says. "The French didn't manage the land at all well," she says. "The process of soil erosion really began then. And then in the chaos after the revolution, the land was simply parcelled out into little plots, occupied mainly by individual families. And since the 1950s, people have been cutting it down and cooking on charcoal. As the population has soared, the forests have come down. Haiti is now about 98% deforested. It's extraordinary. You can see it from space. The problem is, it was those forests, those tree roots, that held the soil together. So with every new storm, more topsoil and clay disappears." Arable land is reduced, simply, to rubble. Even before the devastating storms of 2008, Haiti's population was starving. There were shocking reports of desperate people mixing vegetable oil with mud to make something that at least looked approximately like a biscuit. Pause for Analysis 1. What does Von Tunzelmann argue is the reason for Haiti’s poor condition today? List two examples. "I wouldn't lay it all at the door of history," says Keppel. "But it's true to say that while this earthquake was unprecedented and unpredictable and would have caused huge problems anywhere, Haiti is impacted by natural disasters much more than some of its neighbours. The infrastructure is so poor; the government can't control all its territory. There's been a whole combination of factors, many of which have repeated themselves over and over, that have left Haiti in the state it's in today." Among aid workers whom Von Tunzelmann has spoken to, Haiti today is "down there with Somalia, as just about the worst [most damaged] society on earth. Even in Afghanistan, there's a middle class. People aren't living in the sewers." As far back as the 1950s, she says, Haiti was considered unsustainably overcrowded with a population of 3 million; that figure now stands at 9 million. Some 80% of that population live below the poverty line. The country is in an advanced state of industrial collapse, with a GDP per capita in 2009 of just $2 a day. Some 66% of Haitians work in agriculture, but this is mainly small-scale subsistence farming and accounts for less than a third of GDP. The unemployment rate is 75%. Foreign aid accounts for 30%-40% of the government's budget. There are 80 deaths for every 1,000 live births, and the survival rate of newborns is the lowest in the western hemisphere. For many adults, the most promising sources of income are likely to be drug dealing, weapons trading, gang membership, kidnapping and extortion. Pause for Analysis 1. What evidence indicate Haiti is underdeveloped? (List three examples) Compare Haiti with its neighbours, equally prone to natural disasters but far better equipped to cope because they are far better functioning societies, and the only conclusion possible, says Von Tunzelmann, is that it is Haiti's turbulent history that has brought it to this point. For the better part of 200 years, she argues, rich countries and their banks have been sucking the wealth out of the country, and its own despotic and corrupt leaders have been doing their best to facilitate the process, lining their own pockets handsomely on the way. Pause for Analysis 1. What specific parts of Haiti’s history does the author argue “brought it to this point”? Approach Haiti's border with the Dominican Republic and the lush green of the forest begins again: this is a wealthier place. An earthquake here has less impact because constructions are stronger, building regulations are enforced, the government is more stable. In nearby Cuba, hardly a country rolling in money, emergency management is infinitely more effective simply because of a carefully coordinated, block-by-block organisation. Haiti has two fire stations in the entire country – and people on $2 a day cannot afford quake-proof housing. This article was amended on 18 January 2010, to clarify that a reference to Duvalier-era debts constituting 45% of what Haiti owes referred to the situation in 2009, and to clarify that a quote from interviewee Alex von Tunzelmann about the level of social damage in Haiti was her paraphrasing of what aid workers had told her. (Post-Reading) Analysis Questions: 1. Does this article paint an accurate picture of Haiti? Why/why not? Going Beyond the Textbook The Monroe Doctrine What the Textbook says: (Pg. 625) Analysis Questions: 1. Why did the U.S. suddenly find Latin America interesting in 1820? 2. What is a “doctrine”? 3. What is the Monroe Doctrine? a. When was it issued? (Yes, you need to know this date!) b. What did it say? c. What is the U.S.’s motive in issuing this doctrine? d. What was the European perception? Now, let’s go BEYOND!... Excerpts from The Monroe Doctrine James Monroe expressed his thoughts on how foreign policy should be conducted at his seventh annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. His words are considered an essential part of America's political history and became known as "the Monroe Doctrine." .... “The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted. We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. .... Our policy in regard to Europe, which was adopted at an early stage of the wars which have so long agitated that quarter of the globe, nevertheless remains the same, which is, not to interfere in the internal concerns of any of its powers; to consider the government de facto as the legitimate government for us; to cultivate friendly relations with it, and to preserve those relations by a frank, firm, and manly policy, meeting in all instances the just claims of every power, submitting to injuries from none.” Analysis Questions: 1. In what medium was the Monroe Doctrine delivered? 2. Who is Monroe’s audience? Why does this matter? 3. How does Monroe describe the U.S.’s relationship with Europe? 4. What does Monroe mean by “extend their system”? 5. What should Americans think of this ‘extension,’ according to Monroe? How must the U.S. respond? Analysis Questions: 1. How do these political cartoons represent the Monroe Doctrine? 2. How might Latin Americans feel about the policy?