Table of Contents - Western Washington University

advertisement

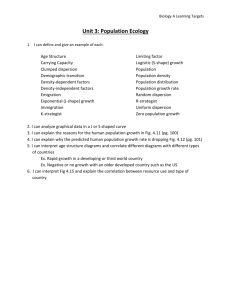

1 Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife: Marine Mammal Investigations Department Internship WDFW/MMI Internship June 2011-Sept.2011 Robert Harvey Western Washington University 2 Table of Contents Section One: Marine Mammals Worked With Harbor Seal (Phoca Vitulina)…………………………………………………….……3 Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus)……………………………………………….….3 California Sea Lion (Zalophus californianus)……………………………………..…..3 Northern Sea Lion/Stellar Sea Lion (Eumetopias jubatus)…………………………....4 Guadalupe Fur Seal (Arctocephalus townsendi)……………………………….……...4 Harbor Porpoise (Phocoena phocoena)……………………………………………….4 Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris)……………………………………4 Northern Fur Seal (Callorhinus ursinus)………………………………………………4 Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)……………………………………………………………...4 Section Two: Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) Necropsy Procedure Introduction……………………………………………………………………………5 External Examination…………………………………………………………….......6-7 Internal Examination………………………………………………………...………7-11 Section Three: Gray Whale Necropsy………………………………………………………..12 Section Four: Captures……………………………………………………………..…...…13-14 Section Five: Major Study Sites………………………………………………………..….15-16 Section Six: Bibliography/ Resources……….………………………………………………..17 3 Marine Mammals Worked With Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina): Harbor seals come in variety of shades of color from white, to grey, to black and everything in between. They generally have spotted coats with contrasting or matching colors to their fur (Fig. 51). Males reach a maximum weight of 370 lbs. and can be 6'3" in length, with a maximum life expectancy of 25 years. Females reach a maximum weight of 200 lbs., reaching 5'7" in length, with a maximum life expectancy on 35 years. Copulation of these animals usually takes place in late December in shallow water, which brings about a significant amount of fighting amongst the males. The gestation period last about 10 months (Sheffer & Slipp). Females give birth to one pup a year, ranging from early spring to late summer, with the peak of the pupping season being dependent on the specific geographical location. In the Puget Sound, the major sites for haling out and giving birth include Woodard Bay, Gertrude Island, and Eagle Island. The peak of the birthing season in the PS is mid-July, but there are pups being born as late as early September each year. The pups remain with their mothers for 4-6 weeks before they are abruptly weaned and abandoned. During this time the pup is fully capable of doubling its initial birth weight due to the extremely high fat content in the mother’s milk. The survival rate of pups in their first year is right around 50%. Factors that contribute to their high death rate include abandonment from mothers, malnourishment, predation (killer whales, dogs, and bear), infection from a wound, and detrimental human interaction (Lambourn). Harbor seals are very skittish animals, with the tendency to spook extremely easy. A hall out of several hundred animals can all simultaneously panic and head into the water from just a seagull flying overhead. Harbor seals can aggregate at hall outs in numbers up to 450 strong. Hall outs include beaches, log booms, large rocks, and buoys. They prefer to hall out on beaches that offer as much access to the water as possible, such as a spit. They prefer this type of environment because it allows easy access to the water if they feel threatened, as they will not venture more than a few yards from the waters’ edge. Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus): They grey whale is one of the more abundant whales in the Pacific Northwest. They have a grey to dark grey color on their generally rough, barnacle crusted skin (Fig. 16). The barnacles are the densest around the head of the animal, with whale lice being distributed all over the body. They are characterized by their molted grey bodies, dorsal bumps, and upon diving have a distinguishable raised fluke. Grey whales can grow upward of 49 feet, and weight over 80,000 lbs. They can live well over 40 years, as long as 75. They are a species of baleen whales, with 130-180 baleen plates in their mouth (Lambourn). California Sea Lion (Zalophus californianus): California sea lions are just one of the many species of sea lions. They are distinguishable by their small ears, lighter colored flippers, and a narrow pronounced snout. Males are very robust at the shoulders, chest, and neck, with a slender hind part. They have a very pronounced forehead with an exaggerated sagital crest. They are capable of reaching up to 860 lbs., and usually are a brown to light brown in color. Females are much smaller than males with slenderer bodies. Their fur color is tan to yellow, and they can reach a max weight of 240 lbs. (Lambourn). 4 Northern Sea Lion/Stellar Sea Lion (Eumetopias jubatus): Stellar sea lions (or northern sea lion) are the largest of the eared seal family, with a notable robust head and body. They have a short blunt and broad snout, contrary to the California sea lion. They have broad, dark brown to black fore flippers with short and slim, lighter colored hind flippers (Fig. 50). Males are often lighter in color than males. Males can reach a max weight of 2,400 lbs. and be 11 feet long. Females can weigh up to 770 lbs. and reach 9'6" in length (Lambourn). Guadalupe Fur Seal (Arctocephalus townsendi): Guadalupe fur seals are characterized by their narrow pointed snout, particularly males, and their short, dark hind flippers. They have a uniformly dark fur, usually really thick around male’s neck. Males can weigh up to 490 lbs. and reach 7'3" in length. Females weigh up to 121 lbs. and can reach 6'3" in length (Lambourn). Harbor Porpoise (Phocoena phocoena): These porpoises have the name that they do because they prefer the sanctuary of harbors and inlets, as opposed to open waters. They are relatively difficult to spot, as they have a very quick roll with little or no splashing when they surface to breath. Their backs are dark gray, with lighter color on the sides and belly. They have small body, being one of the smaller porpoise species, with a triangular dorsal fin at the top. Males reach a maximum weight around 134 lbs. and a length of 5'2". Females reach a maximum weight of 168 lbs. and a length of 5'6" (Lambourn). Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris): Elephant seals are characterized by the large inflatable air sack that sits on adult males noses, primarily used to ward off potential threats on a males stretch of beach. These seals have a very robust torso, which tapers down to narrow hips and short fore flippers. Males can weigh up to 4,400 lbs. and reach 13'6" in length. Females are considerably smaller, reaching a maximum weight of 1,300 lbs. and a length of 10' (Lambourn). Northern Fur Seal (Callorhinus ursinus): These fur seals are distinguishable by their small heads, short snouts, and blunt noses. Their bodies are small and stocky, with relatively long hind flippers that have long digit tips. Males develop massive chest and shoulders that act as extra protection in territorial disputes with other males. Males reach a maximum weight of 600 lbs. and reach 6'11" in length. Females are much smaller, weighing up to 132 lbs. and have a length of 4'11" (Lambourn). Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris): Sea otters are very large in size compared to other members of the otter family, as males can weigh up to 100 lbs., and be over 4' in length. They have extremely dense fur, essential to maintain their body temperature in cold water. They have short broad heads and short blunt snouts. Sea otters spend a significant amount of their time floating and swimming on their backs, where they feed and rest (Lambourn). 5 Harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) Necropsy Procedure Necropsies are performed in order to gain further insight into the cause of death, specifically with marine mammals. A properly performed necropsy creates a series of internal and external observations that all contribute to reaching a diagnosis. By consistently performing necropsies, trends in overall population health of a species can be monitored. About one fourth of the 300 hours spend this summer working with Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife in the Marine Mammal Investigations department was dedicated to performing necropsies on dead pinnipeds ( which includes both eared, and earless seals). The majority of the animals that necropsied were harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), as they are the most abundant marine mammal in the Puget Sound. Due to their large numbers, there is a constant flow of calls coming into the department during the summer months of animals stranded, dead, or on the verge of death. Unfortunately there is a very high death rate amongst pups during the summer months. I took part in roughly 25 different harbor seal necropsies over the course of my internship. There are several different ensuing investigations and sampling methods used to narrow down the cause of death. These investigations are made from testing different samples of body parts from the necropsied animal. They include histopathology, which is “…the microscopic examination of tissue in order to study the manifestations of disease” (Pugliares). Another is cytology, which are impression smears that are taken from an open wound or any surface that are died and stained, and can be examined on site. Virology is a common analysis performed, with samples most frequently being taken from the lungs, serum, brain, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Sampling for microbiology with sterile swabs is very common, as well as sampling for parasitology, which is the collection of parasites from the animal. Sampling for toxins includes sampling for contaminants, which are any toxins of or chemicals present in the marine environment that are potentially consumed by marine mammals, thus integrated into their tissues (Pugliares). Samples for biotoxins are taken, which are “naturally occurring toxins produced by dinoflagellates and other marine algae that accumulate in animals as they are passed through the food web” (Pugliares). Finally, life history and genetics are considered. Compilations of teeth, skin, stomach contents, reproductive organs, and skeletons all can be used to determine, “age estimation, genetics, trophic position, habitat usage, and reproductive status” (Pugliares). Samples would be taken from all animals and sent to several different labs across the country and in Canada. We would take a portion of each sample and place it them in formalin for WDFW analysis and record keeping. The following is the process of a typical necropsy in sequential order for a small pinniped. 6 External Exam Condition Code: Prior to starting any necropsy, the carcass condition must be accessed to determine to what extent sampling should be conducted on the animal. Ideally, necropsies are performed within the first 48 hours of death but this is often not case. There is a five scaled system that correlates to the condition of the animal. Code 1 means that the animal is still alive. Code 2 is a fresh carcass, meaning the animal has been dead for roughly 24 hours. Code 3 is moderate decomposition, which might include bloating, sloughing skin, and some scavenging. Code 4 implies advanced decomposition, meaning the skin is completely sloughing, there is a strong odor, considerable scavenging, liquefied internal organs, and lose muscle around the bones. Code 5 includes mummification of just skeletal remains. A code 5 is relatively useless except for extracting specific pieces of the skeleton (Pugliares). Nutritional Condition: The nutritional condition of a pinniped is dictated by looking at the pelvic and neck region of the animal, creating 3 classes: robust, thin, and emaciated. A robust animal will have a nice round shape, with no visible bone structure. In a thin animal, the pelvic and neck bones will be slightly noticeable. An emaciated animal will have obvious protruding pelvic bones, visible neck bones, and an outline of the rib cage as well. (Pugliares) Most dead animals we encountered were in the thin to emaciated range, with the exception of harbor seal pups. Dead pups were usually either very robust, appearing fat and healthy, or very emaciated with little to no blubber. This always raised the question to what is worse: a dead pup that was abandoned and extremely malnourished that never really had a chance, or a healthy fat pup that had a lot of it mothers time and energy put into its success, yet it still failed to make it? Sex Determination In order to determine the sex of a pinniped, the ventral surface of the animal must be examined. Males will have a penile opening below the umbilical scar, with the penis bone being visible through the skin in some cases. Females will have two horizontally spaced teats below the umbilicus. You can also examine the perianal region of the animal, as males will only have an anal opening, while females with have an anus and vagina. Integument Observation A further external inspection of the animal should include a description of the eyes, ears, mouth, nostrils, genital area, umbilicus (mainly for pups), anus, fur, and skin (Fig.4). Any abnormalities seen should be noted and possibly examined further. Open wounds or abrasions are noted, as well as any fungal disease or obvious external parasite or infection. Skin and Teeth Sampling A portion of skin is removed between the digits of the left rear flipper. The upper left and right canine tooth is also removed. The teeth serve as vital clues to determine the age of the animal, as well as possible infection of the mouth. 7 Skin and Blubber Removal With the animal ventral side up, an incision is made under the jaw that runs parallel down the animal to the anus. Perpendicular cuts are then made off the main incision a few inches apart down the length of the animal, creating a series of panels. The blubber is then removed with the skin in each panel, exposing muscle and the internal body cavity. During this process it is important to look for any bruising, parasites, or signs of hemorrhaging. Samples of blubber are almost always taken. Skeletal Muscle Removal After the blubber has been removed, the exposed muscle should be examined closely for any signs of hemorrhaging or bruising. The color and texture of the muscle is examined, as well as any signs of disproportion of muscle mass. Muscle is usually taken for samples, and in doing this I learned the hard way it is important not to cut open the internal body cavity until muscle has been removed. Internal Examination Scapula and Prescapular Lymph Node With the animal still ventral side up, cut away the connective tissue holding the front flippers and scapula to the body wall. You locate the prescapular lymph node, which should be somewhere between the scapula and body on the cranial side of the bone (Pugliares). A normal lymph node should appear round or oval shaped, have a firm consistent texture, and be light brown to purple in color. Any abnormality in the size, shape, color, or texture of the lymph node should be noted, which is usually correlative to a reaction. (Fig. 10) Thyroid The thyroids are located on either side of the trachea of the animal. They usually appear dark purple, have flat circular shape, and have a texture resembling that of smooth muscle. They usually are taken for sampling. Thymus Found most commonly in neonates (up to 4 weeks old) and juveniles, the thymus is large lymphoid organ. This organ is unique, in that as time passes, it is absorbed after weaning and is not usually found in adult pinnipeds (Pugliares). Its primary function is to produce T-cells, which is critical in development of immune cells during early development with pups. Opening the Rib Cage To open the thoracic cavity and rib cage, trim away any connective muscle attached to the rib cage. Starting with the top rib, find the cartilaginous “sweet spot” (Pugliares) in the middle of the ribs. This flexible spot is what allows for deep inhalation and exhalation. Continue to open and spread the rib cage until the entire thoracic cavity is open, exposing all of the internal organs. Note for any obvious abnormalities such as discolorations, excess fluid accumulation, or lesions. (Figs. 5, 6) Lungs 8 The lungs occupy the most space within the thoracic cavity, with tissue that’s usually bright to dark pink in color with a spongy texture. To detach the lungs, severe their connection to the trachea, then remove from the cavity (Fig. 7). Normal lungs should be relatively firm and air filled, which can be tested by applying pressure with a finger and seeing if they bounce back, or placing in formalin and seeing if they float. To internally examine, begin with an incision in the trachea and work your away posterior into the bronchioles of each lung (Pugliares). Look for and note any present parasites, froth, or fluids. Emphysema is common in dead animals. Trachea The trachea is a long, flexible, tubular organ connected to the lungs. Cut open the trachea slowly with scissors all to the apex of the throat. Look for mucus build up, froth, blood, or any abnormal discoloration. Heart Muscle and Valves Prior to removing the heart, note any abnormality in size, color, and texture of the right and left atria and ventricles, aorta, and pulmonary valves. Remove the heart by cutting transversely across the aorta and pulmonary artery, making sure to leave ~5.0 cm of each vessel attached to the heart muscle (Lambourn). To open the heart, take scissors and “…make a small opening in the right atrium and cut down along the peripheral edge of the right ventricle to the down the apex. Continue cutting along the right ventricle side of the septum until this chamber joins the pulmonary artery and cut up through this vessel. Next, snip the left ventricle side of the apex cut through the muscle along the septum, and continue through the aorta” (Pugliares). This will result in the heart being fully open and intact. Inspect each chamber carefully for any worms or other foreign material. The left ventricle should be considerably thicker than the right. Diaphragm The diaphragm is a thin, dark colored, smooth muscle attached to the rib cage. It separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Look for any tears or adhesions to the diaphragm, and note any unusual texture or color found throughout it. Trim away the diaphragm enough to have access to the abdominal organs. Liver The liver should be found lying across the stomach, and should occupy a significant amount of space in the abdominal cavity. It is usually purple in color and “multi-lobular” (Pugliares). Note any color patterns or blotches of color, as well as any variation in texture throughout. Take a thin slice of the liver from the midsection and note any abnormalities in the cross section. (Fig. 9) Gall Bladder The gall bladder can be found tucked between the livers lobes. It is dark green to green/brown in color, fairly thick walled, and round. Bile is almost always collected here to check for contaminants by a sterile syringe and needle, and upon removal it can be opened up further for examination. Waiting to remove the gall bladder before opening it up is important because it stops other organs from being contaminated by bile once it is opened. Check for and note any small stones or parasites found (Lambourn). 9 Spleen The spleen is mottled purple to white, flat, thin organ located underneath the stomach against the left side of the body. It is common for pinnipeds to have uneven jagged spleens. Remove the spleen, and on both the surface and interior of the spleen, note shape, size, color, and texture. (Fig. 9) Pancreas The pancreas is usually peach colored, inconsistently shaped, relatively soft and attached to the mesentery and rest along the small intestines (Pugliares). Remove it from the cavity by detaching it from the mesenteric tissue. Note the size, shape, color, and texture of the surface. Then cut a cross section and look for any changes in color or texture. Mesentery and Mesenteric lymph node The mesentery is an extremely thin connective tissue band that is attached to the intestines. This tissue should be translucent and be difficult to initially cut, as it should be pretty tough to tear. Examine the mesentery for any abnormal adhesions, thickening in places, or any noticeably thin portions. The mesenteric lymph node is a banana shaped, dark tan to gray colored, lymph node that is suspended in place by the mesentery. Cut the mesenteric lymph node out of the mesentery and examine the interior and exterior for any changes in color or texture (Lambourn). Adrenal Glands The left and right adrenal glands are located anterior to the base of the kidneys, attached to the abdominal wall. They are small, oblong, light purple, with irregular grooves covering the surface. Always remove the adrenals before the kidney, because the kidney serves as an important reference point. Remove the adrenals by severing the connective tissue holding them to the body wall. Examine the exterior, then slice in half and note the inside of them. The cross section should show a dark center, gradually getting lighter outward. Note abnormal sized adrenals always (Pugliares). Kidneys The left and right kidneys purple to maroon in color, egg shaped, covered in cluster of “reniculi” (miniature kidneys) and are attached to the dorsal abdominal wall” (Pugliares). There is a thin capsule surrounding the kidneys, examine this for any fluids or abnormal bumps, noting its color and thickness. Cut the kidney out, observing the size, shape, color, and texture of each kidney individually. Cut a cross section and examine the inside of each kidney. Look for any difference in the size of the two kidneys. (Fig. 8) Urinary Bladder The urinary bladder is relatively small, light red to light pink in color, located anterior to the pelvic bone against the ventral body wall (Pugliares). It is usually thick walled, but if it is enlarged with urine it is thin walled and can be semi-translucent. Before the bladder is removed, a sterile syringe and needle is used to extract urine. With extracted urine, we would routinely perform ‘in house’ domoic acid test. After urine extraction, remove the bladder and examine it internally by cutting along the length of the organ. Note the color and texture of the inside, and look for any signs on infection. 10 Female-Ovaries and Uterus The uterus and ovaries can be recognized by tracing the reproductive tract starting at the vagina, working your way to the uterus where it splits to the left and right, with both ends ending at the ovaries (Pugliares). The uterus is usually tan in color with varying size and thickness, which is correlated to the sexual maturity and size of the animal. The size of the uterus is also an indicator of the animal’s sexual history. Note the size, shape, and color of the uterus. If a fetus is present and is too small or an individual necropsy, open up the abdomen and collect sterile swabs and preserve the fetus in formalin. The ovaries are attached to the end of each uterine horn, usually a grey to yellow white in color. Detach the ovaries from the uterus and exam the external side, noting its size, shape, and color. A mature animal’s ovary will have random, dark scars, indicating it has had previous ovulations. A pregnant female will have a large yellow mass attached to the ovary. Examine each ovary individually, counting its scars and compare the size of the two (Lambourn). Male-Testes The testes are spindled shaped, light gray to tan in color, and located outside of the abdominal cavity, along the ventral wall next to the hip bones. Remove the testis, taking measurements of both, noting any difference in size, color, or texture between the two. Cut at least one open and examine internally as well. Stomach Prior to removing the stomach, both ends need to be tied off with zip ties. This is done in order to so no material inside is lost during the extraction process. Once tied off, remove the stomach and examine the exterior for and significant discolorations or lacerations. Weight the stomach while it is still tied off, then open the stomach and empty its contents into sieves. Note the composition of the stomach contents including, fish bones, fully or partially digested food, rocks, seaweed, parasites, shells, or any foreign trash. If any foreign objects are found, photograph and document it under human interaction. Once the stomach is empty, examine the lining of it, noting the color and texture of the internal folding, look for any ulcers, parasites, or discoloration. Finally, weight the stomach when it is empty. Esophagus Follow the esophagus from the posterior end to the mouth. Open by making slow cuts with scissors, starting posterior. Note the internal lining, looking for any froth, abnormal texture or color, and any other contents. Small Intestines The intestines are always done toward the end of the necropsy in order not to contaminate other organs with its insides. Look for areas of hemorrhaging or any parasites of the surface. The inside is usually not examined, but in the case it was we would randomly spot check it by making 5-10 random incisions, evenly spaced (Lambourn). Any abnormalities should be noted. (Fig. 9) Large Intestines 11 The large intestines is examined in the exact manner as the small intestines, and in many cases the time was not taken distinguish between the two. Colon Examine the surface for any areas of discoloration. Opening the posterior end of the colon, place a whirl pack bag on the open end and squeeze out any feces remaining in the animal. Note color and texture of the feces. Removal and Examination of the Brain The brain is the most delicate and easily disrupted organ the body, so extreme care must be taken in the removal process. It took me two botched attempts, resulting in mangled brain samples until I was able to master the technique. The head must first be detached from the body. Once it is remove all of the excess skin, fat, and muscle from the back of the skull. Using a bone saw make two parallel cuts along the sides of the skull starting at the back and working forward till the sagittal crest. Then make a perpendicular cut along the crest, intersecting the two prior cuts at their ends. This should result in a squared off U shape. It is important to fully penetrate the bone without penetrating the brain. Slowly pry open the back of the top of the skull upward, exposing the brain. Slide your finger along the base of the now open skull, severing any small connections still held on the side of the skull. If done correctly, it should pop off with no damage inflicted to the brain. Note the external surface of the brain for color, texture, any parasites, or lesions (Fig 11). In the case sterile brain samples were requested for a specific animal, extra steps were taken in removal. Prior to opening the skull, a torch is lit to sterilize a clean scalpel for removing a top piece of brain that is immediately placed in cultured falcon tube. Once the brain is exposed, the scalpel and base of the falcon tube are heated, and the brain sample it immediately placed inside and sealed off. Skull Cleaning Many of the heads taken off the seals were flensed down to remove as much muscle, skin, and blubber as possible. They would then be placed in mesh bags and boiled in a bleach solution, until the remaining scraps had fallen off completely or were cooked enough to be cut off (Fig. 12). The skulls and sets of teeth were sent off to different laboratories, and a good number of them stayed with WDFW for record keeping. 12 Gray Whale Necropsy On July 27, 2011 a Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) was alive and stranded at Erlands Point in Bremerton, WA. It was a juvenile male, 3 to 5 years in age, 30 feet long, and an estimated 25,000lbs (Fig 16). The animal was beached on an outgoing tide, apparently too weak to swim out with it. WDFW responded and monitored the animal, doing our best to keep it alive. Unfortunately the animal remained beach, and since the massive animal was no longer buoyant in the water, it suffocated under its own weight. We arrived on site the next morning on July 28, around 7 AM to begin the necropsy procedure. The animal was lying on its ventral side in several feet of water in the outgoing tide. With 15 individuals we tried to roll the animal on its side for easier access to its organs, but to avail. It was decided the necropsy would be performed with the whale on its stomach. The animal was covered in lacerations and sea lice, with a substantial amount of barnacles located around the head (Fig. 52). The process began with flensing away sections of blubber on the whale’s side. Being such a malnourished and small gray whale, its blubber depth was relatively shallow (Figs. 18, 20). Once opened, the necropsy process for the most part follows that of a pinniped (i.e. harbor seal) necropsy. Several samples were taken of all body parts (Fig. 22) including, blubber, skin, baleen plates, muscle, brain, kidneys (Figs. 26, 27), testes, lungs, intestines, pancreas, spleen, liver, lungs, and heart. These samples are highly desired, as fresh whale samples are not that common. Samples were sent to labs across the country, to Canada, and kept for WDFW records. The initial cause of death was assumed to be from malnourishment. The whale was extremely thin for its length, leading us to conlclude it had beached itself in shallow water and lacked the strength necessary to swim off. It will be several months before the reports come back to WDFW as to what other problems the animal was experiencing internally. The carcass disposal process was taken care of by a local Native American tribe, who voluntarily towed the whale away at an ensuing high tide. 13 Captures WDFW conducts several large scale harbor Seal (Phoca vitulina) captures annually in the south Puget Sound area. The main purpose of this is to monitor the population for diseases, evaluate individual and overall health, and to track individual animals. Working with NOAA, Cascadia Research Collective, veterinarians from around the state and assisted by the McNeil Island Fire Department, mass captures are conducted on Gertrude Island every September during several different days. September is chosen because the animals are usually done giving birth, and are in a relaxed recuperation state. The capture site is at the end of a long spit, surrounded by 270º of water, where the animals are located (Fig. 29). The process is very rehearsed and tactical, as hauling in up to 40 harbor seals at once is quite the task. A 300 foot long, twelve foot wide, lead lined bottom, buoyed topped net is used to capture the animals. There are three boats involved in the process of throwing the net, each with its own responsibility (Fig 30). The lead boat holds the pre stacked net, the hook boat follows, and the ‘scare’ boat makes up the rear. The lead boat accelerates in a slingshot manner around the spit, throwing one of the buoyed ends at the starting place of where the animals are hauled out. The hook boat follows, hooking the end of the thrown net with a gaff and pulling it to shore, while the lead boat hooks around the end of the spit. During this process, my position was front man on the hook boat. It was my job to gaff the end of the net thrown, jump off the boat and run it to shore. The scare boat stays in the water at the center of the net, revving the engine, yelling, and slapping the water with paddles to scare the animals. This commotion is aimed at panicking the animals back toward shore and stopping as many as possible from slipping under the net. The lead and hook boats are at this point both on shore, and with several individuals at each end, they begin pulling in the net. The net is pulled to the sides of the beach, concentrating the animals toward the middle. Being my second year participating in captures and being comfortable with handling seals, I was assigned one of the three positions of pulling the animals one by one out of the net. We would target the pups and smaller females first, followed the larger adults. This part in the process is considered the most dangerous; being that an angry harbor seal can inflict significant damage to a person if given the chance. Pulling the seals by their hind flippers, we drag them up the beach and throw a “hoop net” over individual animals to secure them (Fig.33). Spacing the animals apart so they are not fighting amongst themselves, the beach is at this point littered with about 25 captured seals (Fig 31). One individual is assigned the job of checking on each animal periodically and cooling them with seawater. A portable weight station is set up (Fig. 34), along with two tagging/ branding areas, a portable stove to head the branding irons, and a and tagging prep. station (Fig. 35). After being weighed, sexed, and measured, my job was to move individual animals from hoop nets to the tagging/ branding station and restrain them during the process (Fig. 36). To minimize stress on the animals we always point their head in the direction of the water and lay a wet cloth over their eyes (Fig. 38). I would then straddle the animals, pinching them with my knees and holding the top of the head, all while trying to use the least amount of necessary force. Occasionally, there are seals weighing in the order of 200 lbs. that require several people to hold down. I learned this 14 the hard way when I rode a large adult male several yards down the beach before help came to restrain him (Fig. 44). Once controlled, blood is drawn from each animal which goes into the centrifuge back at the lab to obtain serum. The blood is also used to check for different diseases. Blubber, fur, and whisker samples are also taken at this time (Fig. 40). Each animal is then assigned a combination of color coded ribbons that are tagged to their hind flippers, which are recognizable for re-sight and tracking purpose (Fig. 42). Each animal is then assigned a specific 3 digit number for adults, or a 2 digit number for healthy pups. A scuba tank of compressed air is used to completely dry fur prior to branding. The branding process does not hurt the animals, as it just chars the fur, never getting close to their blubber or bare skin (Fig. 43). A few pups we catch that are in good health are not branded, and have a satellite tracking devices adhered to their backs. The devices do not hurt the animal and usually fall off with the seals first full molt. When each animal has been fully processed through, the eye cover is removed, and the animal is released. For the most part they head straight for the water; however the occasional irritated animal will turn around and snap at you. These individuals usually just require a gentle nudge in the rear. 15 Major Study Sites Gertrude Island One of my favorite jobs was observing and studying beached seals at several of the major Puget Sound hall outs. The purpose of these observation periods was to collect as many re-sights of branded and tagged animals, get a pup count, get a total head count, look for injured or sickly animals, and to monitor behavior. Everything seen or heard is meticulously written down and transferred to the WDFW data base. All of this information summed up results in a relatively accurate representation of the animals migration around the Sound, their overall health, total numbers, and pup mortality rate. The major study site and the breeding ground for harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) in the Puget Sound are on Gertrude Island. Gertrude is a 10 acre island, located within Still Harbor on the northwest side of McNeil Island. The south end of Gertrude Serves as the major hall out area, as it offers a ~300ft long, east curving sand spit with 15-25° slopes of both sides (Fig 45) (Babson & Skidmore). The spit serves as perfect resting, mating, birthing site for seals, due to its 270° encirclement of water, allowing for quick escape if they feel threatened. Gertrude serves as an ideal study site because it falls within the parameters of the former McNeil Island Penitentiary, and the currently operating Special Corrections Facility. There is a 100 yard security limit that circles McNeil, including Gertrude (Fig. 46). This allows wildlife to exist almost completely undisturbed, as I encountered raccoons, bald eagles, and deer on every single outing that had little fear of humans. I was fortunate enough to be cleared to visit the island via ferry as a WDFW intern, and once on McNeil we had a state truck used to get to where we needed to go. There were two methods for observations: pack a bag for the day and cross the low tide land bridge (Fig. 47), or sit in one of our two blinds with a spotting scope and study the seals from a distance (Figs. 48, 49). These surveys were conducted several times a week at Gertrude across the summer months, with all of the counts and re-sights being cataloged for study. Woodard Bay Woodard Bay is located in South Puget Sound, branching off to the south west of Henderson Inlet. The bay was a former area for major log transport out of the south sound, which shut down operations in the mid-1980s (Lambourn). Left behind were a series of log booms that quickly developed into a major harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) hall out area. This is an ideal hall out in that it offers a 360° encasement of water, allowing for easy escape for the seals in threatened. Being that I lived 5 minutes away, I frequented Woodard with a spotting scope. Several times a week I recorded and re-sights, pup counts, etc. What I observed were an increasing number of animals leading up to the peak of pupping season, followed by a drastic decline in consistent numbers of hauled out animals. The reason for this local immigration, followed by emigration is centered on females hauling out just to give birth. Once birth has taken place, the animals would remain in the area for a while, giving the pup the opportunity to fatten up and for the mother to regain its weight. During this period the mother provides massive amounts of milk to the pup, and therefore must constantly be in search of food. 16 Following the pupping season, the majority to the seals leave Woodard Bay as their major hall out, but there are still animals present year round in this area. Eagle Island Eagle Island is a small island located in the South Sound, north of Anderson Island and south of McNeil Island. It once was a major harbor seal haul out (Phoca vitulina) in the Puget Sound, but after it was declared a state park, the numbers of animals that frequent the island has significantly decreased (Lambourn). Constant human visitors to the island contributed mostly to this, as well as increased noise and boat traffic in the area. Still, up to 100 animals can at times be seen hauled out on the northeast corner of the island. Counts can be taken from the south shore of McNeil island, but to get re-sights we would approach with a small boat to get as close as possible. 17 Bibliography Babson, John W., Skidmore, James. “A Conservation Plan for a Colony of Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina) Gertrude Island, WA.” Washington Department of Game (1981) Lambourn, Dyanna. Personal Interviews. June 23-September 12 2011 Pugliares, Katie R., Bogomolni, Andrea., Touhey, Kathleen M., Herzig, Sarah M., Harry, Charles T., Moore J. Michael. 2007 Sept. “Marine Mammal Necropsy: An introduction guide for stranding responders and field biologist”. Buzzards Bay, MA., Woods Hole, MA: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. WHOI-2007-06: 29-52 Scheffer, T.H., Slipp, J.W. “The Harbor Seal in Washington State.” Am. Midl. Nature 32 (1944): 373-416