1967 - Middle East Studies Center at Portland State University

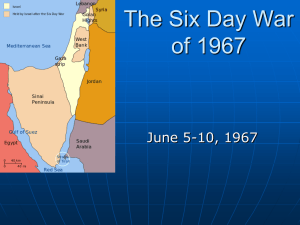

1967: The Six-Day War

Much of today's conflict between Israel and the Palestinians stems from a war 40 years ago that lasted less than a week.

By Sam Roberts

Even by Middle East standards, the spring of 1967 was a tense time. Israel was periodically being attacked by Palestinian guerrillas in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, territories controlled by Egypt and Jordan respectively, and Syrian troops were lobbing artillery fire from the Golan Heights.

In April, Israel retaliated by downing six of Syria's

Soviet-made fighter planes. After the Soviet Union spread rumors that Israel was planning to attack

Syria, the Egyptian army mobilized 100,000 troops and 1,000 tanks in the Sinai

Peninsula. The following month, Egypt's President, Gamel Abdel Nasser, whose stated goal was the destruction of Israel, ordered United Nations observers to leave the area.

He also blockaded the Strait of Tiran, cutting off Israel's access to the Red Sea, a vital shipping route.

With war appearing inevitable, Israel decided to strike first. On the morning of June 5

— while most Egyptian pilots were eating breakfast and their commanders were stuck in rush-hour traffic —the Israeli Air Force destroyed more than 300 of Egypt's 340 combat planes, most before they had a chance to leave the ground. Israeli troops then swept into Gaza and Sinai, as Jordan, with backup from Iraq, began shelling the Israeli sector of Jerusalem. Syria then attacked from the north.

New Map

By June 7, Israel had captured the West Bank and East Jerusalem, including the Old

City, home to many sacred sites in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. By the fourth day,

June 8, with the Egyptians in retreat, Israeli forces had reached the Suez Canal. Two days later, after Israel captured the Golan Heights, Israel and Syria declared a ceasefire.

In six days —actually, a little less—Israel more than tripled the amount of land under its control, rewriting the map of the Middle East.

While the war demonstrated Israel's military superiority in the region, it settled nothing:

Even in the face of a humiliating defeat, Arab leaders remained committed to Israel's destruction. And Israel's occupation of areas with a Palestinian population at the time of about three-quarters of a million led to new woes on both sides, most of which remain unresolved 40 years later.

Arafat & The P.L.O.

Indeed, even before the war ended, as the Israeli government debated trying to capture the West Bank town of Hebron, another city with a rich biblical history, Israel's Prime

Minister asked his colleagues: "Have you already thought about how we can live with so many Arabs?"

The answer would soon become clear enough. A few months after the war ended, a

West Bank revolt led by Palestinian guerrilla leader Yasir Arafat failed, but would nonetheless have a lasting impact. According to Yezid Sayigh, a historian at King's

College in London, the revolt "catapulted the general Palestinian public into the arms of the guerrillas because they'd seen that the people they'd hinged their hopes on —the

Arab leaders and the armies they'd believed in

—had been swept aside in a matter of days."

Two years after the war, Arafat's Fatah movement took control of the Palestine

Liberation Organization (P.L.O.), a group founded by Arab leaders to represent

Palestinian interests. With Arafat as chairman, the P.L.O. waged a decades-long guerrilla war against Israel.

In the last four decades, attempts to bring peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors have in some cases succeeded, but hope has often given way to more violence.

In November 1967, the U.N. endorsed Resolution 242, a "land for peace" formula that has so far been only partly fulfilled: Israel would withdraw from the territories it captured in return for diplomatic recognition from its Arab neighbors and secure borders.

Yom Kippur War

Six years later, in 1973, Egypt and Syria launched surprise attacks on Israel on the

Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, pushing into Sinai and the Golan Heights. By the time the three-week-long conflict was over, Israel had largely repelled the attacks, though with the U.S. mediating after the war, Israel agreed to return part of the Sinai and the

Golan Heights to Egypt and Syria.

Overall, the war restored some of the Arab pride that had been so badly wounded in

1967, arguably enabling some of the peace efforts in the decades that followed.

In 1977, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat astonished the world by announcing that he was ready to go to Jerusalem and meet with Israel's leaders. A year after Sadat's trip to

Israel, U.S. President Jimmy Carter brought Sadat and Israel's Prime Minister,

Menachem Begin, to Camp David, the presidential retreat in Maryland, where the three men broke a 30-year stalemate in the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Egypt & Jordan

The Camp David Accords led to a formal peace treaty in 1979 between Israel and

Egypt: Israel returned the rest of the Sinai, and Egypt became the first Arab state to recognize Israel. (Other Arab states denounced the treaty, and Sadat was assassinated in Cairo in 1981, as he reviewed a parade commemorating the 1973 war.)

Jordan signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1994, but Israel and the Palestinians have remained, in essence, at war. Thousands have died on both sides in two Palestinian uprisings, or intifadas , in Israeli military campaigns in the occupied territories, and in suicide bombings and other attacks on Israelis.

Israel wants the Palestinians to renounce terrorism and genuinely accept its existence, while the Palestinians seek statehood, a capital in Jerusalem, and the right of

Palestinian refugees displaced by the 1948 war to return to Israel.

"Each people believes that justice is totally on its own side," David Shaham, executive director of the International Center for Peace in the Middle East, wrote in The Times some years ago. "Each nurtures its own sufferings and grievances and remains almost completely oblivious to that of the other."

In 2000 at Camp David, President Bill Clinton brought the two sides to the brink of an agreement: Israel would return to its pre-1967 borders, with adjustments, and the

Palestinians would get an independent state with a capital in East Jerusalem, in return for the Palestinians' destroying all terrorist groups. But Arafat, to the consternation of

Clinton and even Arafat's Arab allies, walked away from the negotiations.

According to Leslie Gelb, a former State Department official, Camp David's failure demonstrates the difficulties of bringing the two sides together.

"Israelis said if the Palestinians won't buy this great deal, they don't want peace," Gelb says. "The Palestinians said this was an Israeli trick. The result is what we've seen all these years."

Within months of the collapse of the Camp David talks, a second, more violent intifada began. Militants carried out dozens of suicide bombings in Israel, and Israel responded with a harsh military crackdown.

The U.S. Role

In the last few years, Israel has been trying to unilaterally "disengage" from the

Palestinians. It began construction of a controversial security barrier to keep suicide bombers from entering Israel, and in 2005, shuttered its settlements in Gaza and withdrew its forces, leaving all of Gaza under the control of the Palestinian Authority. In the West Bank, different areas remain under Israeli, Palestinian, or joint control.

In 2006, Hamas, a radical fundamentalist group that calls for Israel's destruction, won a majority in the Palestinian parliament, leading the U.S. and other nations to cut off most aid to the Palestinians and refuse to deal with Hamas members of the government.

Most Middle East experts believe that Israel and the Palestinians will eventually reach agreement, but only when moderates on both sides have gained the upper hand over extremists.

Gelb predicts that a final settlement "will be close to the Camp David terms on almost all issues."

Until then, "it's important for the U.S. to keep the negotiating flame lit, and for the moderates on each side to keep connections and avoid despair.

"But conservatively," Gelb says, "it will be years before the two sides are in a position to make a final settlement."