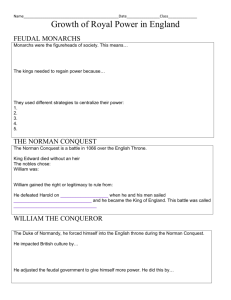

REVIVAL AND THE GROWTH OF ROYAL POWER IN

advertisement

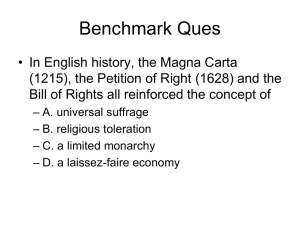

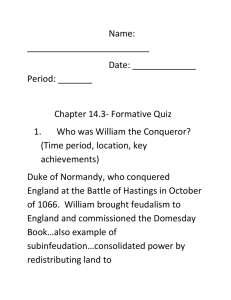

REVIVAL AND THE GROWTH OF ROYAL POWER IN LATER MIDDLE AGES (excerpts from Western Civilization text book) Monarchs, Nobles, and the Church We know that in the Early Middle Ages, the power of kings was on the decline. They ruled their own royal estates, but relied on lords for military support. Their noble lords had as much—and usually far more--power than the king. Both nobles and the Church had their own courts, collected their own taxes, and raised their own armies. In the High Middle Ages, determined kings began to expand their power once again. They set up a system of royal law that replaced feudal laws or Church courts. Now people looked to the king and his courts for justice, not to the local lord. Kings put in place a government organization—a bureaucracy of officials who worked for the king. They developed a system of taxation, and built an army of paid solders (mercenaries), no longer relying on the lords for military service. Monarchs strengthened ties with the middle class. Townspeople, in turn, supported kings who could impose the peace and unity that were needed for trade and commerce. Strong Monarchs in England At the end of Roman times, Britain, like everywhere else in Western Europe, was invaded. First Germanic tribes called the Angles and the Saxons, and later the Vikings, invaded and settled in England. In 1066, the last Anglo- Saxon king died without an heir. His death triggered a power struggle that changed the course of English history. Duke William of Normandy, a French nobleman, claimed the English throne. The English resisted and it took a battle to settle things. Western Europe in 1066 William sailed across the English Channel and at the Battle of Hastings, William and his Norman knights triumphed over the English. On Christmas Day, 1066, William the Conqueror, was crowned and became William I, king of England William the Conqueror William Builds the Monarchy. Once in power, William I took steps to ensure firm control over his new lands. Like other feudal monarchs, he granted lands to his Norman lords, but unlike other feudal kings, he kept a large amount of land for himself (called the royal domain). Determined that lords would not be able to set up power centers beyond his control, he strictly controlled who built castles and where. He required every vassal to swear an oath of loyalty to him called the Salisbury Oath, which made all land holders swear first loyalty to William. He did, however, call regular meetings of his nobles for "parleys" or discussions. These meetings of the king's Great Council developed over the centuries into the institution of Parliament. In 1086, to establish firm financial control over England, William had a complete survey taken county by county. The result was the Domesday Book (pronounced doomsday), which listed every castle, field, and pigpen in England. Information in the Domesday Book helped William and his successors build an efficient system of tax collecting. To effectively govern his kingdom, William appointed royal officials called sheriffs to be his representative in each of the counties or “shires” of England. These royal officials represented the beginning of a government bureaucracy that would grow over time, building centralized royal government in England. William's successors strengthened two keys to royal power: support of the towns and creation of a unifying system of royal or “common” law. Henry II A little less than 100 years after the Norman Conquest, Henry II, inherited the throne and reigned for thirty-five years (1154-1189). The growth of towns and commerce was a factor of real importance in the reign of Henry II. He granted towns royal charters that supported the right to elect local government in return for paying taxes to the king. Henry II reorganized the old method of collecting taxes-based on how much land you owned—because this method failed to recognize the nature of town wealth. Henry’s new tax was assessed as a percentage of a subject’s annual income from trade. It was in the field of law, above all else, that Henry II made his unique contribution. Indeed, he has been called, perhaps without exaggeration, the father of English Common Law. He was determined to expand the system of royal justice, replacing both feudal law and Church law in England. He sent out traveling justices to enforce royal laws. The decisions of the royal courts became the basis for English Common Law, or law that was common--the same-for all people. In time, people chose royal courts over those of nobles or the Church. Henry II was still faced with the big problem of maintaining local law and order without a police force. In 1176, he ordered that juries of twelve men from each county and four men from each town be required to meet periodically. These juries were obliged to report the names of criminals to the king's sheriff or traveling justice, asking more like a police force. When traveling justices visited an area, local officials collected a jury, or group of twelve men sworn to speak the truth. Henry's efforts to extend royal power led to a bitter dispute with the Church. Henry claimed the right to try clergy in royal courts, but the Church had traditionally had its own system of law called Canon Law and its own courts. Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury and once a close friend of Henry's, opposed the king's move. In 1170, four of Henry's knights, believing they were doing Henry's bidding, murdered the archbishop in his own cathedral. Henry denied any part in the attack. Still, to make peace with the Church, he gave up on his attempts to regulate the clergy. King John King John and Magna Carta. Henry's son John came to the throne after the death of his older brother Richard the Lion-Hearted. John angered his own nobles with heavy-handed taxes and other abuses of power. In 1215, a group of rebellious lords revolted against John and forced him to sign the Magna Carta, or great charter. In this document, the king promised to respect a long list of noble rights. Besides protecting their own privileges, the nobles included clauses recognizing the rights of townspeople and the Church. The Magna Carta contained two basic ideas that in the long run would shape government traditions in England. First, it said that the nobles had certain rights. Over time, the rights that had been granted just to the nobles were extended to all English people. Second, the Magna Carta made clear that even the monarch must obey the law. Magna Carta helped establish the idea of limited or constitutional monarchy, which said the king’s power were not absolute. Development of Parliament. Over time, Parliament (which started out as a group of noble advisors called from time to time) grew in power and became a vital part of the idea of limited monarchy. It also, over time, included representatives other than nobles. In 1295, Edward I summoned Parliament to approve money for his wars in France. There was often a need for more money that caused kings to call Parliament into session. This meeting, however, would be different. "What touches all," he declared, "should be approved by all." For the first time, Edward called on representatives of the "common people" to join the lords and clergy. Historians later called this assembly the Model Parliament because it set up the framework for England's twohouse legislature. In time, the House of Lords with nobles and high clergy and the House of Commons with knights and middle-class citizens became the two ‘Houses” of Parliament. Edward I (Longshanks) English monarchs summoned Parliament for their own purposes, but over the centuries, Parliament won the right to approve any new taxes. With that power, Parliament could insist that the monarch meet its demands before voting for taxes. In this way, it could check, or limit, the power of the monarch.