Rhythm Rhythm is a complex aspect of Frost`s poetry. Mostly, writers

advertisement

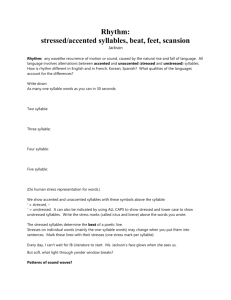

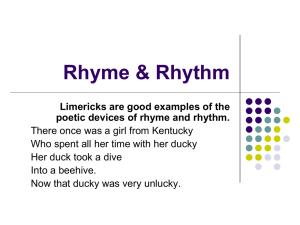

Rhythm Rhythm is a complex aspect of Frost’s poetry. Mostly, writers of student notes make a brief reference to rhythm and leave it at that. But in a Frost poem, rhythm needs to be explained in detail. Frost used rhythm to create meaning. You’ve got to use your ear to judge the rhythm. So, read the poem aloud. Frost had a complex attitude to rhythm. He claimed that he wanted to represent the rhythm of ordinary speech in his poems. But he was also a conservative. That means that he tried to write poetry according to the rules of the great poets he had read. In the past, most poets used the rhythm known as iambic pentameter. The beat of each line is based on a unit of sound known as a foot. The iambic foot is by far the most common type of foot. The iambic foot has two syllables. The second syllable of the pair is the loudest. In other words, it is a stressed syllable. A line of poetry with five of these iambic feet is known as iambic pentameter. ‘Penta’ comes from the Greek word for five. In traditional poetry, the most popular type of line had ten syllables. Usually such lines were divided into five pair of syllables for the purpose of beat or rhythm. This is the beat that Frost admired and tried to use in his poetry. You can see iambic pentameter in many of Frost’s lines. Take ‘Mending Wall’ as an example of rhythm in Frost’s poetry. There is a regular rhythm created by the five beats per line. Consider the opening line as an example of this rhythm or tempo: ‘Something…there is...that does…n't love… a wall’. [Two syllables… Two syllables… Two syllables… Two syllables… Two syllables…] This was the most common tempo or rhythm in poetry down through the ages. In this quoted line, there are two syllables per beat. The second syllable of each beat is loud or stressed. This type of rhythm is known as iambic pentameter. In his early poetry, Frost kept to traditional rules of rhythm. In his later poetry, he relied more on the rhythm of the voice in normal speech when writing his poetry. Did traditional metre or rhythm decide the basic rhythm of ‘Mending Wall’? Trust your ear to judge the rhythm. To comment on rhythm, quote a typical line and show the rhythm that you hear in the line. So, you should read or listen again to ‘Mending Wall’. As well as the formal five even beats or iambic feet, your ear may hear a more natural rhythm. The same line that was analysed just above can be read as a four beat line: ‘Something…there is...that doesn't love… a wall’. [Two syllables…two syllables…four syllables…two syllables] In this reading of the poem the stressed syllable may be any syllable—just trust your ear: ‘thing…is…love…wall. The voice emphasizes the last syllable of each beat] This way of reading the line is based on the human voice and ear as it deals with both the sound and meaning of the words. In fact, the human voice increasingly replaced formal poetic meter in Frost’s mature poetry. You can find just the same pattern in reading to and listening to the rest of ‘Mending Wall’. Consider line sixteen: ‘To each…the boulders…that have fallen… to each…’ [Two syllables…three syllables…four syllables…two syllables, with various syllables stressed—each...bould…fall…each] In fact, while your trained eye may see the five beat rhythm, your ear is more likely to lead you to the four beat rhythm, especially if you read for meaning. You may also reach this conclusion just by sounding the poem out in your head. Try it. Overall, Frost aspired towards a natural rhythm in the sounding out of his poems. Thus there are two contrasting rhythms, the silent formal metre and the natural beat of the reading voice