Handbook for Theology and Religious Studies

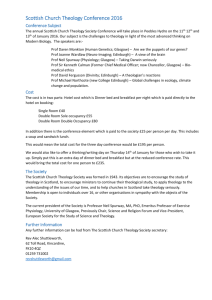

advertisement