Here - National Weather Association

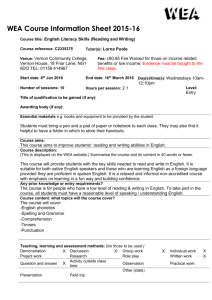

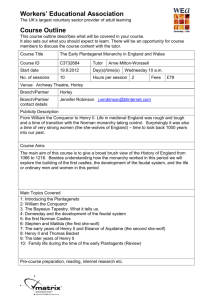

advertisement

Last_name, First_initial. Middle_initial., YYYY: Title. Electronic J. Operational Meteor., Volume (Number), pagepage. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– NWA EJOM Images of Note Title of Paper Here FIRST M. LAST NOAA/National Weather Service, Rapid City, South Dakota (Manuscript received Day Month Year; in final form Day Month Year) _______________ 1. Introduction This section should provide some context leading up to the imagery. Discuss the purpose of your note. What phenomena are depicted in the images? Why are these phenomena important to operational meteorology? Discuss prior research relevant to your paper. Do not make reference to the figures in this section. Citations should be chronological and not alphabetical (i.e., Davies-Jones 1984, 1986; Bunkers et al. 2000); however, the reference list at the end of the paper should be alphabetical. Markowski’s (2002) review paper is rich with references, so you can consult this for general guidance. Notice how commas and semicolons were used—and not used—in the above citations. 2. Discussion This should be the meat of your paper. This is where the figures should first be introduced. The text should describe and evaluate the atmospheric processes at work in the imagery. Relate your discussion of the imagery to the references included in the Introduction. Briefly describe the datasets used to create the imagery. Use two spaces between sentences. Double-space your text. Use 2.54-cm (1in) margins. Adhere to SI units whenever possible with English units in parenthesis (refer to the previous sentence). Define all non-standard acronyms when they first appear, and then stick with the acronym thereafter. Cite figures chronologically. Always abbreviate figures (e.g., Fig. 1) unless they begin a sentence. Figure 2 is an example of an appropriate figure. Moreover, figures should be placed at the end of the paper, and not embedded within the manuscript. 3. Summary As briefly as possible, summarize what was presented in the previous two sections. Speculation should be kept at a minimum. Acknowledgements. Remember to thank people who helped you! REFERENCES Brown, R. A., B. A. Flickinger, E. Forren, D. M. Schultz, D. Sirmans, P. L. Spencer, V. T. Wood and C. L. Ziegler, 2005: Improved detection of severe storms using experimental fine-resolution WSR-88D measurements. Wea. Forecasting, 20, 3–14. Doswell III, C. A., H. E. Brooks, and N. Dotzek, 2009: On the implementation of the Enhanced Fujita scale in the USA. Atmos. Res., 93, 554–563. Dowell, D. C., C. R. Alexander, J. M. Wurman, and L. J. Wicker, 2005: Centrifuging of hydrometeors and debris in tornadoes: Radar-reflectivity patterns and wind-measurement errors. Mon. Wea. Rev., 133, 1501–1524. __________ Corresponding author address: Dr. Matthew J. Bunkers, National Weather Service, 300 E. Signal Dr., Rapid City, SD 57701-3800 E-mail: matthew.bunkers@noaa.gov Kumjian, M. R., and A. V. Ryzhkov, 2008: Polarimetric signatures in supercell thunderstorms. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 47, 1940–1961. Magsig, M. A., and J. T. Snow, 1998: Long-distance debris transport by tornadic thunderstorms. Part I: The 7 May 1995 supercell thunderstorm. Mon. Wea. Rev., 126, 1430–1449. Markowski, P. M., 2002: Hook Echoes and Rear-Flank Downdrafts: A Review. Mon. Wea. Rev., 130, 852–876. NSSL, cited 2011: 2011 Spring Tornado Outbreaks. [Available online at http://www.nssl.noaa.gov/news/2011/.] NWS, cited 2011: Historic Tornado Outbreak April 27, 2011. [Available online at http://www.srh.noaa.gov/bmx/?n=event_04272011.] Rasmussen, E. N., J. M. Straka, M. S. Gilmore, and R. Davies-Jones, 2006: A preliminary survey of rear-flank descending reflectivity cores in supercell storms. Wea. Forecasting, 21, 923–938. Ryzhkov, A., D. Burgess, D. Zrnic, T. Smith, and S. Giangrande, 2002: Polarimetric analysis of a 3 May 1999 tornado. Preprints, 21st Conf. on Severe Local Storms, San Antonio, TX, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 639–642. [Available online at http://ams.confex.com/ams/pdfpapers/47348.pdf.] ____, T. J. Schuur, D. W. Burgess, and D. S. Zrnic, 2005: Polarimetric tornado detection. J. Appl. Meteor., 44, 557– 570. WDTB, cited 2011: Dual-Pol Radar Applications: Tornadic Debris Signatures. [Available online at http://www.wdtb.noaa.gov/courses/dualpol/Applications/TDS/player.html.] 2 Figure 1. Put figure captions below each figure. Figure captions can be single-spaced. Figures should be clearly legible with the font sufficiently large enough so you can read it. Include distance scales and north arrows when needed, such as in this case. Keep figures on separate pages for ease of review. Similar figures can have the same number but different letters (e.g., Figs. 1a, 1b, and 1c). 3 Figure 2. Radar reflectivity at 0012 UTC 30 October 2000 for the lowest four elevation angles (as annotated) from Molokai, HI (PHMO). The heights AGL of the storm centroid at each progressive angle are 687, 1751, 2738, and 3662 m (2254, 5744, 8982, and 12011 ft, respectively). A small yellow fiducial mark is indicated on each frame to illustrate midlevel overhang. The distance across an individual frame is 102 km (55 n mi). 4