Death and Burial - Phoenix Union High School District

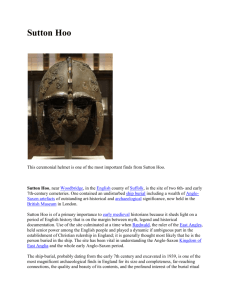

advertisement

Death and Burial in the Anglo-Saxon World The Anglo-Saxon worldview was dominated by a fatalistic view of life. Fate, wyrd, dictated who would live and die, and, in a world full of blood fueds and wars, death was more than just a fact of life; it was a way of life. From elegies such as "The Wanderer" and "The Seafarer" we know that the Anglo-Saxons deeply mourned the passing of friends and family. They wrote tributes to loved ones, lamenting their losses, and they designed the final resting places of the dead in kind. Whether the gone were honored in cremation or burial, it is in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries that we can learn the most about their culture. S. Chadwick Hawkes writes that: … abandoned homes rarely yield more than building foundations and the kinds of objects people threw away. Their cemeteries on the other hand, contain the things treasured by the AngloSaxons, their mortal remains and the precious possessions which they sought to take with them after death. (24) Through the study of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, we have gained a significant amount of information about what the AngloSaxons were like. We have found jewelry, tools, weapons, and other items that give an insight into not only the daily life of the people, but also the afterlife that they expected. While the initial excavations of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries were not held to rigid scientific standards, leading to the loss of much scientific data, there have still been major breakthroughs that, as is the way with these sorts of things, give only as many answers as they conjure up new questions. Many Anglo-Saxon gravesites were disturbed before scientists ever reached them. Robbers throughout history have looted barrows for their rich stores of treasure. In Anglo-Saxon times this was common, and it is parallelled in the story of the dragon's horde in Beowulf. The taboo against disturbing the resting places of the dead is nearly universal, and it was certainly a frightening and potentially risky affair to rob graves. When scientists began exploring AngloSaxon cemeteries, in the eighteenth century, their motives were not so far removed from the grave robbers of yore. The focus was on collecting the grave goods from the different burial sites, and, as Hawkes notes, "skeletons were often disregarded and the historical value of the cemetery as a whole was largely ignored" (24). Because of the ruthlessness of this practice, many scientists began focusing on scientific archaeological excavation of settlements, but those excavations revealed only deteriorated foundations and the objects that people threw away. Interest was again swayed back to the cemeteries, but now with an eye turned less toward gathering the treasures of the AngloSaxons, and more toward the anthropological and archaeological information that could be gathered by closely analyzing skeletons, burial positions, grave proximities, and the like (24). The Anglo-Saxons disposed of their dead either through cremation, depositing the ashes of the deceased in highly ornate urns, or inhumation, usually in the form of barrows. Because of the inherent difficulty in aging, sexing, or identifying cremations, most of the studies focus on the inhumed remains of individuals. Barrows are an ancient form of burial in the British Isles. The practice dates back thousands of years to the times of the most ancient human inhabitation of the land. The Anglo-Saxons built barrows to honor their dead nobles. The size of a barrow is proportional to the importance of the individual buried there. It is difficult to discover the exact social status of inhumed bodies, but the idea that barrows were reserved for the elite of the Anglo-Saxon society is supported by two facts: Not everybody was given a barrow burial, and in barrows there are usually several individuals interred. Anglo-Saxon literature supports this assumption. Beowulf wants to have a giant barrow built in his honor, and he makes this wish as he lays on his death bed. Oftentimes there is an initial interment in a barrow. There is a main grave, and around this grave there may be several bodies that were buried at around the same time. It can be speculated that these additional skeletons may be those of wives or servants of the noble for whom the barrow was built, but this cannot be verified for certain. Scientists have also found that in large barrows are secondary burials of cremation urns. They presume that the urns belong to family members of the deceased and that in this way the barrows may have served as plots for less illustrious family members (Grinsell, 92-3). Depending on the social status of the deceased, barrows range from small bumps to large, complex discs. The most impressive barrows are huge man-made hills, surrounded by a ditch and possibly a rock wall. Less important individuals may have only a small bump on the ground, almost indistinguishable after a millennium. A typical Anglo-Saxon cemetery of interest is Finglesham, in East Kent. The site was used from ca. 500 to ca. 700, and was almost certainly founded by the aristocracy. Finglesham is derived from the Old English, Pengels-ham, which translates to Prince's Home or Prince's Manor. The large barrow of the cemetery has been numbered 204, and from the sheer size of the mound it is obvious that he was quite wealthy. The site was discovered in 1928 by workers who were chalk quarrying. Thirty-one graves were found between 1928 and 1929, and another 215 graves were excavated "more scientifically" between 1959 and 1967 (Hawkes, 24). The founding male, located in grave 204, is supposed to have died at the age of 25 around the year 525. He is interred in a large, iron-bound coffin, and among other treasures found in his grave is a green, glass claw goblet. He was found with both domestic and imported weapons, shields, jewelry, and tools, exhibiting the cosmopolitan nature of Anglo-Saxon society. Surrounding his burial site are the graves of what are assumed to be family members and consorts. Each of these skeletons was found surrounded by items of similar extravagance to the founding male. It is assumed that over half of the population that was buried in Finglesham died by age 25, but the assumption is complicated by the difficulties in ageing or sexing skeletons. According to Jeremy Huggett, from the University of Glasgow, it is difficult to sex a skeleton that is under 25, and it is difficult to age a skeleton that is over 25. Until recently, sex was determined by the gender relationships scientists drew according to grave goods found with the skeleton. This has been shown faulty since sometimes men were buried with brooches, a useful item to an Anglo-Saxon without zippers, but one which many scientists attribute to females. Skeletal evidence has also shown that females were occasionally buried with weapons, although the reasoning behind the coupling of a female skeleton with a 'male' weapon perplexes researchers (Huggett). If Finglesham is an example of a typical AngloSaxon cemetery, Sutton Hoo is an example of the exceptional capability the Anglo-Saxons had in creating monuments. The site is dominated by a huge ship burial, one of the few of its kind found in the British Isles. The site is the tomb of a seventh-century king, discovered in 1939. Excavation of the site lasted until the late 1960s, and still all of the questions researchers have about the cemetery have not been answered. James Campbell describes the unique royal grave: A ship had been dragged from the river Deben up to the top of a 100-foot-high bluff, and laid in a trench. A gabled hut had been built amidships to accommodate a very big coffin and an astonishing collection of treasures and gear. The trench had then been filled in and a mound raised over it to stand boldly on the skyline. (32) Campbell goes on to note that the site had not been disturbed until its discovery by modern scientists. Treasures included personal ornaments inlaid with gold and garnets, weapons, the famous "Sutton-Hoo helmet," silverware, kitchen and cooking equipment, coins, and a "ceremonial whetstone" (32). The items originated from various locations, as far away as the outskirts of Europe, Alexandria, and Byzantium. The variety of treasures and their cosmopolitan nature show the extent to which the Anglo-Saxons interacted with mainland cultures. The question remains, however, of just who is buried at Sutton Hoo. Some scientists want to say that it is the grave of Redwald, a powerful Anglo-Saxon king who died in the 620s. There are 37 coins of Merovingian origin, the latest dating from the 620s, that suggest the time frame is right for the assertion of the site as Redwald's grave. Scholars also point to two silver spoons that were found in the treasure. One is engraved with PAULOS, and the other SAULOS. Some scientists say these were given to Redwald upon his baptism into Christianity, and that the mixture of pagan and Christian elements in the burial site supports this. Indeed, the ship burial is generally associated with pagan cultures. But others claim that the burial of a ship points to the influence of the Swedes on the Anglo-Saxons, and go so far as to say that it is a Swedish individual who rose to power in the British Isles. Still others point to the origin of the coins and say that it must have been an individual with close ties to Gaul, possibly a king from that area. Regardless, it is a truly fascinating treasure that rewards speculation with only more unanswerable questions (Cambell, 33). In only the last hundred years of scientific examination of Anglo-Saxon burial sites, scientists have discovered a wealth of knowledge equaled only by the wealth of treasure they have also gleaned from various barrows and graves. While these discoveries have mainly led to new questions that defy answer, the evidence that researchers have gathered have given a certain amount of perspective to other cultural artifacts from the Anglo-Saxon period. Scholars are using the empirical evidence of archaeologists and anthropologists to give new meaning to ancient texts. Through the study of Anglo-Saxon grave sites we become close to the objects the people held dear, and through the combination of their various forms of creative output, be it in manufacturing items or texts, we become closer to their civilization. Sutton Hoo Macmillan Encyclopedia of Death and Dying | 2002 | CARVER, MARTIN | Copyright The Sutton Hoo burial ground in East Anglia, England, provides vivid evidence for attitudes to death immediately before the conversion of an English community to Christianity in the seventh century C.E. Founded about 600 C.E., and lasting a hundred years, Sutton Hoo contained only about twenty burials, most of them rich and unusual, spread over four hectares. This contrasts with the "folk cemeteries" of the pagan period (fifth–sixth centuries C.E.), which typically feature large numbers of cremations contained in pots and inhumations laid in graves with standard sets of weapons and jewelry. Accordingly, Sutton Hoo is designated as a "princely" burial ground, a special cemetery reserved for the elite. The site was rediscovered in 1938, and has been the subject of major campaigns of excavation and research in 1965– 1971 and 1983–2001. Because the majority of the burials had been plundered in the sixteenth century, detailed interpretation is difficult. The Sutton Hoo burial ground consists of thirteen visible mounds on the left bank of the River Deben opposite Woodbridge in Suffolk, England. Four mounds were investigated by the landowner in 1938– 1939; all are from the seventh century C.E., and one mound contains the richest grave ever discovered on British soil. Here, a ship ninety feet long had been buried in a trench with a wooden chamber amid other ships containing over 200 objects of gold, silver, bronze, and iron. The conditions of the soil mean that the body, timbers of ship and chamber, and most organic materials had rotted to invisibility, but the latest studies suggest that a man had been placed on a floor or in a coffin. At his head were a helmet, a shield, spears and items of regalia, a standard, and a scepter; at his feet were a pile of clothing and a great silver dish with three tubs or cauldrons. Gold buckles and shoulder clasps inlaid with garnet had connected a baldrick originally made of leather. Nearly every item was ornamented with lively abstract images similar to dragons or birds of prey. The buried man was thought to be Raedwald, an early king of East Anglia who had briefly converted to Christianity, reverted to paganism, and died around 624 or 625. Investigations at Sutton Hoo were renewed in 1965 and 1983, and revealed considerably more about the burial ground and its context. In the seventh century, burial was confined to people of high rank, mainly men. In mounds five to seven, probably among the earliest, men were cremated with animals (i.e., cattle, horse, and deer) and the ashes were placed in a bronze bowl. In mound seventeen a young man was buried in a coffin, accompanied by his sword, shield, and, in an adjacent pit, his horse. In mound fourteen, a woman was buried in an underground chamber, perhaps on a bed accompanied by fine silver ornaments. A child was buried in a coffin along with a miniature spear (burial twelve). Mound two, like mound one, proved to have been a ship burial, but here the ship had been placed over an underground chamber in which a man had been buried. Because the graves were plundered in the sixteenth century, interpretation is difficult. The latest Sutton Hoo researcher, Martin Carver, sees the burial ground as a whole as a pagan monument in which burial rites relatively new to England (under-mound cremation, horse burial, ship burial) are drawn from a common pagan heritage and enacted in defiance of pressure from Christian Europe. The major burials are "political statements" in which the person honored is equipped as an ambassador of the people, both at the public funeral and in the afterlife. A second phase of burial at Sutton Hoo consisted of two groups of people (mainly men) who had been executed by hanging or decapitation. The remains of seventeen bodies were found around mound five, and twentythree were found around a group of post-sockets (supposed to be gallows) at the eastern side of the burial mounds. These bodies were dated (by radiocarbon determinations) between the eighth and the tenth centuries, and reflect the authority of the Christian kings who supplanted those buried under the Sutton Hoo mounds in about 700 C.E.