ART Sutton Hoo - WBR Teacher Moodle

advertisement

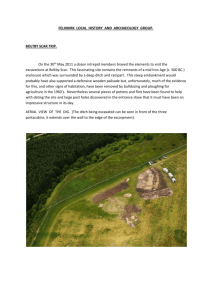

Sutton Hoo This ceremonial helmet is one of the most important finds from Sutton Hoo. Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge, in the English county of Suffolk, is the site of two 6th- and early 7th-century cemeteries. One contained an undisturbed ship burial including a wealth of AngloSaxon artefacts of outstanding art-historical and archaeological significance, now held in the British Museum in London. Sutton Hoo is of a primary importance to early medieval historians because it sheds light on a period of English history that is on the margin between myth, legend and historical documentation. Use of the site culminated at a time when Rædwald, the ruler of the East Angles, held senior power among the English people and played a dynamic if ambiguous part in the establishment of Christian rulership in England; it is generally thought most likely that he is the person buried in the ship. The site has been vital in understanding the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of East Anglia and the whole early Anglo-Saxon period. The ship-burial, probably dating from the early 7th century and excavated in 1939, is one of the most magnificent archaeological finds in England for its size and completeness, far-reaching connections, the quality and beauty of its contents, and the profound interest of the burial ritual itself. The initial excavation was privately sponsored by the landowner, but when the significance of the find became apparent, national experts took over. Subsequent archaeological campaigns, particularly in the late 1960s and late 1980s, have explored the wider site and many other individual burials. The most significant artefacts from the ship-burial, displayed in the British Museum, are those found in the burial chamber, including a suite of metalwork dress fittings in gold and gems, a ceremonial helmet, shield and sword, a lyre, and many pieces of silver plate from the Eastern Roman Empire. The ship-burial has from the time of its discovery prompted comparisons with the world described in the heroic Old English poem Beowulf, which is set in southern Sweden. It is in that region, especially at Vendel, that close archaeological parallels to the ship-burial are found, both in its general form and in details of the military equipment that the burial contains. Although it is the ship-burial that commands the greatest attention from tourists, there is also rich historical meaning in the two separate cemeteries, their position in relation to the Deben estuary and the North Sea, and their relation to other sites in the immediate neighborhood. Of the two grave fields found at Sutton Hoo, one (the "Sutton Hoo cemetery") had long been known to exist because it consists of a group of around 20 earthen burial mounds that rise slightly above the horizon of the hill-spur when viewed from the opposite bank. The other, called here the "new" burial ground, is situated on a second hill-spur close to the present Exhibition Hall, about 500 m upstream of the first, and was discovered and partially explored in 2000 during preparations for the construction of the hall. This also had burials under mounds, but was not known because they had long since been flattened by agricultural activity. The site has a visitor's centre, with many original and replica artefacts and a reconstruction of the ship burial chamber, and the burial field can be toured in the summer months. Location The Wicklaw region Sutton Hoo is the name of an area spread along the bank of the River Deben opposite the harbour of the small Suffolk town of Woodbridge. About 7 miles (11 km) from the sea, it overlooks the tidal estuary a little below the lowest convenient fording place.[note 1] It formed a path of entry into East Anglia during the period that followed the end of Roman imperial rule in the 5th century.[2] South of Woodbridge, there are 6th-century burial grounds at Rushmere, Little Bealings and Tuddenham St Martin[3] and circling Brightwell Heath, the site of mounds that date from the Bronze Age.[4] There are cemeteries of a similar date at Rendlesham and Ufford.[5] A ship-burial at Snape is the only one in England that can be compared to the example at Sutton Hoo.[6] The territory between the Orwell and the watersheds of the Alde and Deben rivers may have been an early centre of royal power, originally centred upon Rendlesham or Sutton Hoo, and a primary component in the formation of the East Anglian kingdom:[note 2] in the early 7th century, Gipeswic (modern Ipswich) began its growth as a centre for foreign trade,[7] Botolph's monastery at Iken was founded by royal grant in 654,[8] and Bede identified Rendlesham as the site of Æthelwold's royal dwelling.[9][10] Early settlement Neolithic and Bronze Age There is evidence that Sutton Hoo was occupied during the Neolithic period, circa 3000 BCE, when woodland in the area was cleared by agriculturalists. They dug small pits that contained flint-tempered earthenware pots. Several pits were near to hollows where large trees had been uprooted: the Neolithic farmers may have associated the hollows with the pots.[11] During the Bronze Age, when agricultural communities living in Britain were adopting the newly introduced technology of metalworking, timber-framed roundhouses were built at Sutton Hoo, with wattle and daub walling and thatched roofs. The best surviving example contained a ring of upright posts, up to 30 millimetres (1.2 in) in diameter, with one pair suggesting an entrance to the south-east. In the central hearth, a faience bead had been dropped. The farmers who dwelt in this house used decorated Beaker-style pottery, cultivated barley, oats and wheat, and collected hazelnuts. They were responsible for creating ditches that marked out the surrounding grassland into sections, indicating land ownership. The acidic sandy soil eventually become leached and infertile, and it was likely that for this reason, the settlement was eventually abandoned, to be replaced in the Middle Bronze Age (1500-1000 BCE) by sheep or cattle that were enclosed by wooden stakes.[12] Iron Age and Romano-British period During the Iron Age, iron became the dominant form of metal used in the British Isles, replacing copper and bronze. In the Middle Iron Age (around 500 BCE), people living in the Sutton Hoo area grew crops again, dividing the land up into small enclosures now known as Celtic fields.[13] The use of narrow trenches implies grape cultivation, whilst in other places, small pockets of dark soil indicate that big cabbages may have been grown.[14] Such cultivation continued into the Romano-British period, from 43 to around 410. Life for the Britons remained unaffected by the arrival of the Romans. Several artefacts from this period, including a few fragments of pottery and a discarded fibula, have been found. As the peoples of Western Europe were encouraged by the Empire to maximise the use of land for growing crops, the area around Sutton Hoo suffered degradation and soil loss, was again eventually abandoned and became a wilderness.[14] Anglo-Saxon cemetery Background Further information: Burial in Early Anglo-Saxon England and Kingdom of East Anglia The kingdom of East Anglia during the early Anglo/Angle-Saxon period, with Sutton Hoo in the southeastern area near to the coast Following the withdrawal of the Romans from southern Britain after 410, the remaining population slowly adopted the language, customs and beliefs of the Germanic Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Much of the process may have been due to cultural appropriation, due to a widespread migration into Britain, although the people that arrived may have been relatively small in numbers and aggressive towards the local populations they encountered.[15] The Anglo-Saxons developed new cultural traits. Their language developed into Old English, a Germanic language that was different from the languages previously spoken in Britain, and they were pagans, following a polytheistic religion. Differences in their daily material culture changed, as they stopped living in roundhouses and constructed rectangular timber homes similar to those found in Denmark and northern Germany. Their jewellery began to exhibit the increasing influence of Migration Period Art from continental Europe.[citation needed] During this period, southern Britain became divided up into a number of small independent kingdoms. Several pagan cemeteries from the kingdom of the East Angles have been found, most notably at Spong Hill and Snape, where a large number of cremations and inhumations were found. Many of the graves were accompanied by grave goods, which included combs, tweezers and brooches, as well as weapons. Sacrificed animals had been placed in the graves.[16] At the time when the Sutton Hoo cemetery was in use, the River Deben would have formed part of a busy trading and transportation network. A number of settlements grew up along the river, most of which would have been small farmsteads, although it seems likely that there was a larger administrative centre as well, where the local aristocracy held court. Archaeologists have speculated that such a centre may have existed at Rendlesham, Melton, Bromeswell or at Sutton Hoo. It has been suggested that when wealthier families buried their dead in burial mounds, these were later used as sites for early churches. In such cases, the mounds would have been destroyed.[17] The Sutton Hoo grave field contained about twenty barrows and was reserved for people who were buried individually with objects that indicated that they had exceptional wealth or prestige. It was used in this way from around 575 to 625 and contrasts with the Snape cemetery, where the ship-burial and furnished graves were added to a graveyard of buried pots containing cremated ashes.[citation needed] Mound 11 (front left), Mound 10 (foreground, masking Mound 1), Mound 2 (middle distance) and Sutton Hoo House The cremations and inhumations, Mounds 17 and 14 Mound 17 (orange), Mound 14 (purple), inhumations (green) and cremation graves (blue) at Sutton Hoo Carver believes that the cremation burials at Sutton Hoo were "among the earliest" in the cemetery.[17] Two were excavated in 1938. Under Mound 3 were the ashes of a man and a horse placed on a wooden trough or dugout bier, a Frankish iron-headed throwing-axe and imported objects from the eastern Mediterranean, including the lid of a bronze ewer, part of a miniature carved plaque depicting a winged Victory and fragments of decorated bone from a casket.[18] Under Mound 4 was the cremated remains of a man and a woman, with a horse and perhaps also a dog, as well as fragments of bone gaming-pieces.[19] In Mounds 5, 6 and 7, Carver found cremations deposited in bronze bowls. In Mound 5 were found gaming-pieces, small iron shears, a cup and an ivory box. Mound 7 also contained gaming-pieces, as well as an iron-bound bucket, a sword-belt fitting and a drinking vessel, together with the remains of horse, cattle, red deer, sheep and pig that had been burnt with the deceased on a pyre. Mound 6 contained cremated animals, gaming-pieces, a sword-belt fitting and a comb. The Mound 18 grave was very damaged, but of similar kind.[20] Two cremations were found during the 1960s exploration to define the extent of Mound 5, together with two inhumations and a pit with a skull and fragments of decorative foil.[21] In level areas between the mounds, Carver found three furnished inhumations. One small mound held a child's remains, along with his buckle and miniature spear. A man's grave included two belt buckles and a knife, and that of a woman contained a leather bag, a pin and a chatelaine.[22] Finds from Mound 17 The most impressive of the burials without a chamber is that of a young man who was buried with his horse,[23] in Mound 17.[24] The horse would have been sacrificed for the funeral, in a ritual sufficiently standardised to indicate a lack of sentimental attachment to it. Two undisturbed grave-hollows existed side-by-side under the mound. The man's oak coffin contained his pattern welded sword on his right and his sword-belt, wrapped around the blade, which had a bronze buckle with garnet cloisonné cellwork, two pyramidal strapmounts and a scabbard-buckle. By the man's head was a firesteel and a leather pouch, containing rough garnets and a piece of millefiori glass. Around the coffin were two spears, a shield, a small cauldron and a bronze bowl, a pot, an iron-bound bucket and some animal ribs. In the north-west corner of his grave was a bridle, mounted with circular gilt bronze plaques with interlace ornamentation.[25] These items are on display at Sutton Hoo. Inhumation graves of this kind are known from both England and Germanic Europe,[note 3] with most dating from the 6th or early 7th century. In about 1820, an example was excavated at Witnesham.[26] There are other examples at Lakenheath in western Suffolk and in the Snape cemetery:[27] other examples have been inferred from records of the discovery of horse furniture at Eye and Mildenhall.[28] Although the grave under Mound 14 had been destroyed almost completely by robbing, apparently during a heavy rainstorm, it had contained exceptionally high-quality goods belonging to a woman. These included a chatelaine, a kidney-shaped purse lid, a bowl, several buckles, a dress-fastener and the hinges of a casket, all made of silver, and also a fragment of embroidered cloth.[29] Mound 2 Mound 2 is the only Sutton Hoo tumulus to have been reconstructed to its estimated original height. This important grave, much damaged by looters, was probably the source of the many iron shiprivets found at Sutton Hoo in 1860. In 1938, when the mound was excavated, iron rivets were found, which enabled the Mound 2 grave to be interpreted as a small boat.[30] Carver's reinvestigation revealed that there was a rectangular plank-lined chamber, 5 metres (16 ft) long by 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) wide, sunk below the land surface, with the body and grave-goods laid out in it. A small ship had been placed over this in an east–west alignment, before a large earth mound was raised.[31] Chemical analysis of the chamber floor has suggested the presence of a body in the southwestern corner. The goods found included fragments of a blue glass cup with a trailed decoration, similar to the recent find from the Prittlewell tomb in Essex. There were two giltbronze discs with animal interlace ornament, a bronze brooch, a silver buckle and a gold-coated stud from a buckle. Four objects had a special kinship with the Mound 1 finds: the tip of a sword blade showed elaborate pattern-welding; silver-gilt drinking horn-mounts (struck from the same dies as those in Mound 1); and the similarity of two fragments of dragon-like mounts or plaques.[32] Although the rituals were not identical, the association of the contents of the grave shows a connection between the two burials.[33] The execution burials "Sand body" preserved for museum display The cemetery also contained a number of inhumations of people who had died by violent means, in some cases by hanging or decapitation. Often the bones had not survived, but the fleshy parts of the bodies had stained the sandy soil: the soil was laminated as work progressed, so that the emaciated figures of the dead could be revealed. Casts were taken of several of these tableaux. The identification and discussion of these burials was led by Carver.[34] Two main groups were excavated, with one arranged around Mound 5 and the other situated beyond the barrow cemetery limits in the field to the east. It is thought that a gallows once stood on Mound 5, in a prominent position near to a significant river-crossing point, and that the graves contained the bodies of criminals, possibly executed from the 8th and 9th centuries onwards. The new grave field In 2000, a Suffolk County Council team excavated the site intended for the National Trust's new visitor centre, north of Tranmer House, at a point where the ridge of the Deben valley veers westwards to form a promontory. When the topsoil was removed, early Anglo-Saxon burials were discovered in one corner, with some possessing high-status objects.[35] The area had first attracted attention with the discovery of part of a 6th-century bronze vessel, of eastern Mediterranean origin, that had probably formed part of a furnished burial. The outer surface of the so-called "Bromewell bucket" was decorated with a Syrian- or Nubian-style frieze, depicting naked warriors in combat with leaping lions, and had an inscription in Greek that translated as "Use this in good health, Master Count, for many happy years."[36] In an area near to a former rose garden, a group of moderate-sized burial mounds was identified. They had long since been levelled, but their position was shown by circular ditches that each enclosed a small deposit indicating the presence of a single burial, probably of unurned human ashes. One burial lay in an irregular oval pit that contained two vessels, a stamped black earthenware urn of late 6th-century type and a well-preserved large bronze hanging bowl, with openwork hook escutcheons and a related circular mount at the centre.[37] In another burial, a man had been laid next to his spear and covered with a shield of normal size. The shield bore an ornamented boss-stud and two fine metal mounts, ornamented with a predatory bird and a dragon-like creature.[38] Mound 1 Mound 1: posts mark the ends of the ship. The ship-burial discovered under Mound 1 in 1939 contained one of the most magnificent archaeological finds in England for its size and completeness, far-reaching connections, the quality and beauty of its contents, and for the profound interest it generated.[39][40] The burial Mound 1 (in red) within the burial ground (possible burial mounds are coloured grey) Model of the ship's structure as it might have appeared, with chamber area outlined Although practically none of the original timber survived, the form of the ship was perfectly preserved.[41] Stains in the sand had replaced the wood but had preserved many construction details. Nearly all of the iron planking rivets were in their original places. It was possible to survey the original ship, which was found to be 27 metres (89 ft) long, pointed at either end with tall rising stem and stern posts and widening to 4.4 metres (14 ft) in the beam amidships with an inboard depth of 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) over the keel line. From the keel board, the hull was constructed clinker-fashion with nine planks on either side, fastened with rivets. Twenty-six wooden frames strengthened the form. Repairs were visible: this had been a sea-going vessel of excellent craftsmanship, but there was no descending keel. The decking, benches and mast were removed. In the fore and aft sections, there were thorn-shaped oar-rests along the gunwales, indicating that there may have been positions for forty oarsmen. The central chamber had timber walls at either end and a roof, which was probably pitched. The heavy oak vessel had been hauled from the river up the hill and lowered into a prepared trench, so only the tops of the stem and stern posts rose above the land surface.[42] After the addition of the body and the artefacts, an oval mound was constructed, which covered the ship and rose above the horizon at the riverward side of the cemetery.[43] The view to the river is now obscured by Top Hat Wood, but the mound would have been a visible symbol of power to those using the waterway. This appears to have been the final occasion upon which the Sutton Hoo cemetery was used for its original purpose.[44] Long afterwards, the roof collapsed violently under the weight of the mound, compressing the ship's contents into a seam of earth.[45] The body in the ship-burial As a body was not found, there was early speculation that the ship-burial was a cenotaph, but soil analyses conducted in 1967 found phosphate traces, supporting the view that a body had disappeared in the acidic soil.[46] The presence of a platform (or a large coffin) that was about 9 feet (2.7 m) long was indicated.[47] An iron-bound wooden bucket, an iron lamp containing beeswax and a bottle of north continental manufacture were close by. The objects around the body indicate that it lay with the head at the west end of the wooden structure. Artefacts near the body have been identified as regalia, pointing to it being that of a king.[48] Most of the suggestions for the occupant are East Anglian kings because of the proximity of the royal vill of Rendlesham.[48] Since 1940, when H.M. Chadwick first ventured that the ship-burial was probably the grave of Rædwald,[49] scholarly opinion divided between Raedwald and his son (or step-son) Sigeberht.[46] The man who was buried under Mound 1 cannot be identified,[50] but the identification with Rædwald still has widespread scholarly acceptance, though from time to time, other identifications are suggested, including his son Eorpwald of East Anglia, who succeeded his father in about 624. Rædwald is the most likely of the candidates because of the high quality of the imported and commissioned materials and the resources needed to assemble them, the authority that the gold was intended to convey, the community involvement required to conduct the ritual at a cemetery reserved for an elite, the close proximity of Sutton Hoo to Rendlesham and the probable date horizons.[note 4] The objects in the burial chamber A replica of the Sutton Hoo helmet produced for the British Museum by the Royal Armouries David M. Wilson has remarked that the metal artworks found in the Sutton Hoo graves were "work of the highest quality, not only in English but in European terms".[51] Sutton Hoo is a cornerstone of the study of art in Britain in the 6th–9th centuries. George Henderson has described the ship treasures as "the first proven hothouse for the incubation of the Insular style".[52] The gold and garnet fittings show the creative fusion of earlier techniques and motifs by a master goldsmith. Insular art drew upon Irish, Pictish, Anglo-Saxon, native British and Mediterranean artistic sources: the 7th-century Book of Durrow owes as much to Pictish sculpture, British millefiori and enamelwork and Anglo-Saxon cloisonné metalwork as it does to Irish art.[note 5] The Sutton Hoo treasures represent a continuum from pre-Christian royal accumulation of precious objects from diverse cultural sources, through to the art of gospel books, shrines and liturgical or dynastic objects. The head area: the helmet, bowls and spoons On the head's left side was placed a "crested" and masked helmet wrapped in cloths.[53] With its panels of tinned bronze and assembled mounts, the decoration is directly comparable to that found on helmets from the Vendel and Valsgärde cemeteries of eastern Sweden.[54] The Sutton Hoo helmet differs from the Swedish examples in having an iron skull of a single vaulted shell and has a full face mask, a solid neck guard and deep cheekpieces. These features have suggested an English origin for the basic structure of the helmet; the deep cheekpieces have parallels in the Coppergate helmet, found in York.[55] Although outwardly very like the Swedish examples, the Sutton Hoo helmet is a product of better craftsmanship. Helmets are extremely rare finds. No other such figural plaques are known in England, apart from a fragment from a burial at Caenby, Lincolnshire.[56] The helmet rusted in the grave and was shattered into hundreds of tiny fragments when the chamber roof collapsed. Restoration of the helmet thus involved the meticulous identification, grouping and orientation of the surviving fragments before it could be reconstructed.[note 6] To the head's right was placed inverted a nested set of ten silver bowls, probably made in the Eastern Empire during the sixth century. Beneath them were two silver spoons, possibly from Byzantium, of a type bearing names of the Apostles.[58] One spoon is marked in original nielloed Greek lettering with the name of PAULOS, "Paul". The other, matching spoon has been modified using lettering conventions of a Frankish coin-die cutter, to read SAULOS, "Saul". One theory suggests that the spoons (and possibly also the bowls) were a baptismal gift for the buried person.[59] The weapons on the right side of the body On the right of the "body" lay a set of spears, tips uppermost, including three barbed angons, with their heads thrust through a handle of the bronze bowl.[60] Nearby was a wand with a small mount depicting a wolf.[61] Closer to the body lay the sword with a gold and garnet cloisonné pommel 85 centimetres (33 in) long, its pattern-welded blade still within its scabbard, with superlative scabbard-bosses of domed cellwork and pyramidal mounts.[62] Attached to this and lying towards the body was the sword harness and belt, fitted with a suite of gold mounts and strap-distributors of extremely intricate garnet cellwork ornament.[63] Upper body area: purse, shoulder-clasps and great buckle Great Buckle Shoulder-clasps Purse lid Together with the sword harness and scabbard mounts, the gold and garnet objects found in the upper body space, which form a co-ordinated ensemble, are among the true wonders of Sutton Hoo. Their artistic and technical quality is quite exceptional.[64] The "great" gold buckle is made in three parts.[65] The plate is a long ovoid of a meandering but symmetrical outline with densely interwoven and interpenetrating ribbon animals rendered in chip-carving on the front. The gold surfaces are punched to receive niello detail. The plate is hollow and has a hinged back, forming a secret chamber, possibly for a relic. Both the tongueplate and hoop are solid, ornamented, and expertly engineered. Each shoulder-clasp consists of two matching curved halves, hinged upon a long removable chained pin.[66] The surfaces display panels of interlocking stepped garnets and chequer millefiori insets, surrounded by interlaced ornament of Germanic Style II ribbon animals. The half-round clasp ends contain garnet-work of interlocking wild boars with filigree surrounds. On the underside of the mounts are lugs for attachment to a stiff leather cuirass. The function of the clasps is to hold together the two halves of such armour so that it can fit the torso closely in the Roman manner.[67] The cuirass itself, possibly worn in the grave, did not survive. No other Anglo-Saxon cuirass clasps are known. The ornamental purse lid, covering a lost leather pouch, hung from the waist-belt.[68] The lid consists of a kidney-shaped cellwork frame enclosing a sheet of horn, on which were mounted pairs of exquisite garnet cellwork plaques depicting birds, wolves devouring men, geometric motifs and a double panel showing animals with interlaced extremities. The maker derived these images from the ornament of the Swedish-style helmets and shield-mounts. In his work they are transferred into the cellwork medium with dazzling technical and artistic virtuosity. These are the work of a master-goldsmith who had access to an East Anglian armoury containing the objects used as pattern sources. As an ensemble they enabled the patron to appear imperial.[note 7][69] The purse contained thirty-seven gold shillings or tremisses, each originating from a different Frankish mint. They were deliberately collected. There were also three blank coins and two small ingots.[70] This has prompted various explanations: possibly like the Roman obolus they may have been left to pay the forty ghostly oarsmen in the afterworld, or were a funeral tribute, or an expression of allegiance.[71] They provide the primary evidence for the date of the burial, which was debatably in the third decade of the 7th century.[72] The lower body and 'Heaps' areas In the area corresponding to the lower legs of the body were laid out various drinking vessels, including a pair of drinking horns made from the horns of an aurochs, extinct since early mediaeval times.[73] These have matching die-stamped gilt rim mounts and vandykes, of similar workmanship and design to the shield mounts, and exactly similar to the surviving horn vandykes from Mound 2.[74] In the same area stood a set of maplewood cups with similar rimmounts and vandykes,[75] and a heap of folded textiles lay on the left side. A large quantity of material including metal objects and textiles was formed into two folded or packed heaps on the east end of the central wooden structure. This included the extremely rare survival of a long coat of ring-mail, made of alternate rows of welded and riveted iron links,[76] two hanging bowls,[77] leather shoes,[78] a cushion stuffed with feathers, folded objects of leather and a wooden platter. At one side of the heaps lay an iron hammer-axe with a long iron handle, possibly a weapon.[79] On top of the folded heaps was set a fluted silver dish with drop handles, probably of Italian make, with the relief image of a female head in late Roman style worked into the bowl.[80] This contained a series of small burr-wood cups with rim-mounts, combs of antler, small metal knives, a small silver bowl, and various other small effects (possibly toilet equipment), and including a bone gaming-piece, thought to be the 'king piece' from a set.[81] (Traces of bone above the head position have suggested that a gaming-board was possibly set out, as at Taplow.) Above these was a silver ladle with gilt chevron ornament, also of Mediterranean origin.[82] Over the whole of this, perched on top of the heaps, or their container, if there was one, lay a very large round silver platter with chased ornament, made in the Eastern Empire in around 500 and bearing the control stamps of Emperor Anastasius I (491–518).[83] On this plate was deposited a piece of unburnt bone of uncertain derivation.[84] The assemblage of Mediterranean silverware in the Sutton Hoo grave is unique for this period in Britain and Europe.[85] The west and east walls The shield-fittings reassembled Along the inner west wall (i.e. the head end) at the north-west corner stood a tall iron stand with a grid near the top.[86] Beside this rested a very large circular shield,[87] with a central boss, mounted with garnets and with die-pressed plaques of interlaced animal ornament.[note 8] The shield front displayed two large emblems with garnet settings, one a composite metal predatory bird and the other a flying dragon. It also bore animal-ornamented sheet strips directly die-linked to examples from the early cemetery at Vendel[89] near Old Uppsala in Sweden.[90] A small bell, possibly for an animal, lay nearby. Along the wall was a long square-sectioned whetstone, tapered at either end and carved with human faces on each side. A ring mount, topped by a bronze antlered stag figurine, was fixed to the upper end, possibly made to resemble a late Roman consular sceptre.[91] The purpose of the sceptre has generated considerable debate and a number of theories, some of which point to the potential religious significance of the stag.[92] South of the septre was an iron-bound wooden bucket, one of several in the grave.[93] In the south-west corner was a group of objects which may have been hung up, but when discovered, were compressed together. They included a Coptic or eastern Mediterranean bronze bowl with drop handles and figures of animals,[94] found below a badly deformed six-stringed Anglo-Saxon lyre in a beaver-skin bag, of a Germanic type found in wealthy Anglo-Saxon and north European graves of this date.[95] Uppermost was a large and exceptionally elaborate threehooked hanging bowl of Insular production, with champleve enamel and millefiori mounts showing fine-line spiral ornament and red cross motifs and with an enamelled metal fish mounted to swivel on a pin within the bowl.[96] At the east end of the chamber, near the north corner, stood an iron-bound tub of yew containing a smaller bucket. To the south were two small bronze cauldrons, which were probably hung against the wall. A large carinated bronze cauldron, similar to the example from a chamber-grave at Taplow, with iron mounts and two ring-handles was hung by one handle.[97] Nearby lay an iron chain almost 3.5 metres (11 ft) long, of complex ornamental sections and wrought links, for suspending a cauldron from the beams of a large hall. The chain was the product of a British tradition dating back to pre-Roman times.[98] All these items were of a domestic character. Textiles The burial chamber was evidently rich in textiles, represented by many fragments preserved, or by chemicals formed by corrosion.[99] They included quantities of twill, possibly from cloaks, blankets or hangings, and the remains of cloaks with characteristic long-pile weaving. There appear to have been more exotic coloured hangings or spreads, including some (possibly imported) woven in stepped lozenge patterns using a Syrian technique in which the weft is looped around the warp to create a textured surface. Two other colour-patterned textiles, near the head and foot of the body area, resemble Scandinavian work of the same period. Comparisons Similarities with Swedish burials A Swedish shield from Vendel Helmet from the 7th century ship burial at Vendel In 1881-1883 a series of excavations by Hjalmar Stolpe revealed 14 graves in the village of Vendel in eastern Sweden.[100] Several of the burials were contained in boats up to 9 metres (30 ft) long and were furnished with swords, shields, helmets and other items.[101] In 1828, another gravefield containing princely burials was discovered at Valsgärde.[102] The pagan custom of furnished burial may have reached a natural culmination as Christianity began to make its mark.[103] The Vendel and Valsgärde graves also included ships, similar artefact groups and many sacrificed animals.[104] Ship-burials for this period are largely confined to eastern Sweden and East Anglia. The earlier mound-burials at Old Uppsala, in the same region, have a more direct bearing on the Beowulf story, but do not contain ship-burials. The famous Gokstad and Oseberg ship-burials of Norway are of a later date. The inclusion of drinking-horns, lyre, sword and shield, bronze and glass vessels is typical of high-status chamber-graves in England.[105] The similar selection and arrangement of the goods in these graves indicates a conformity of household possessions and funeral customs between people of this status, with the Sutton Hoo ship-burial being a uniquely elaborated version, of exceptional quality. Unusually, Sutton Hoo included regalia and instruments of power and had direct Scandinavian connections. A possible explanation for such connections lies in the wellattested northern custom by which the children of leading men were often raised away from home by a distinguished friend or relative.[106] A future East Anglian king, whilst being fostered in Sweden, could have acquired high quality objects and made contact with armourers, before returning to East Anglia to rule. Carver argues that pagan East Anglian rulers would have responded to the growing encroachment of Roman Christendom by employing ever more elaborate cremation rituals, so expressing defiance and independence. The execution victims, if not sacrificed for the shipburial, perhaps suffered for their dissent from the cult of Christian royalty:[107] their executions may coincide in date with the period of Mercian hegemony over East Anglia in about 760– 825.[108] Connections with Beowulf Beowulf, the Old English epic poem set in Denmark and Sweden (mostly Götaland) during the first half of the 6th century, opens with the funeral of a king in a ship laden with treasure and has other descriptions of hoards, including Beowulf's own mound-burial. Its picture of warrior life in the hall of the Danish Scylding clan, with formal mead-drinking, minstrel recitation to the lyre and the rewarding of valour with gifts, and the description of a helmet, could all be illustrated from the Sutton Hoo finds. The interpretation of each has a bearing on the other,[109] and the east Sweden connections with the Sutton Hoo material reinforce this link.[110] Sam Newton draws together the Sutton Hoo and Beowulf links with the Raedwald identification and using genealogical data, argues that the Wuffing dynasty derived from the Geatish house of Wulfing, mentioned in both Beowulf and the poem Widsith. Possibly the oral materials from which Beowulf was assembled belonged to East Anglian royal tradition, and they and the shipburial took shape together as heroic restatements of migration-age origins.[109] Excavations Prior to 1939 In mediaeval times the westerly end of the mound was dug away and a boundary ditch was laid out. Therefore when looters dug into the apparent centre during the sixteenth century they missed the real centre: nor could they have foreseen that the deposit lay very deep in the belly of a buried ship, well below the level of the land surface.[111] In the 16th century, a pit, dated by bottle shards left at the bottom, was dug into Mound 1, narrowly missing the burial.[111] The area was explored extensively during the 19th century, when a small viewing platform was constructed,[112] but no useful records were made. In 1860 it was reported that nearly two bushels of iron screw bolts, presumably ship rivets, had been found at the recent opening of a mound and that it was hoped to open others.[113] Basil Brown and Charles Phillips: 1938-1939 In 1910, a mansion with fifteen bedrooms was built a short distance from the mounds and in 1926 the mansion and its arable land was purchased by Colonel Frank Pretty, a retired military officer who had recently married. In 1934, Pretty died, leaving a widow Edith Pretty and young son.[114] Following her bereavement, Mrs Pretty became interested in Spiritualism, a religion that placed belief in the idea that the spirits of the deceased could be contacted. Some of her Spiritualist friends claimed to have seen 'shadowy figures' around the mounds and one had a vision of a man on a white horse there. Pretty's nephew, a dowser, repeatedly detected the presence of buried gold from what is now known to be the ship-mound,[115][116] reflecting a claim around 1900 by an elderly resident of Woodbridge, of "untold gold" lying under the Sutton Hoo mounds.[117] Such occurrences caught Mrs Pretty's interest and in 1937 she decided to organise an excavation of the mounds.[116] Through the Ipswich Museum, she obtained the services of Basil Brown, a self-taught Suffolk archaeologist who had taken up full-time investigations of Roman sites for the museum.[118] In June 1938, Pretty took him to the site, offered him accommodation and a wage of 30 shillings a week, and suggested that he start digging at Mound 1.[119] Because it had been disturbed by earlier grave diggers, Brown, in consultation with the Ipswich Museum, decided instead to open three smaller mounds (2, 3 and 4). These only revealed fragmented artefacts, as the mounds had been robbed of valuable items.[120] In Mound 2 he found iron shiprivets and a disturbed chamber burial that contained unusual fragments of metal and glass artefacts. At first it was undecided as to whether they were Early Anglo-Saxon or Viking objects.[121] The Ipswich Museum then became involved with the excavations:[122] all the finds became part of the museum's collection. In May 1939, Brown began work on Mound 1, helped by Pretty's gardener John (Jack) Jacobs, her gamekeeper William Spooner and another estate worker Bert Fuller.[123] (Jacobs lived with his wife and their three children at Sutton Hoo House). They drove a trench from the east end and on the third day discovered an iron rivet which Brown identified as a ship's rivet.[124] Within hours others were found still in position. The colossal size of the find became apparent. After several weeks of patiently removing earth from the ship's hull, they reached the burial chamber.[125] A ghost image of the buried ship was revealed during excavations in 1939 The following month, Charles Phillips of Cambridge University heard rumours of a ship discovery. He was taken to Sutton Hoo by Mr Maynard, the Ipswich Museum curator, and was staggered by what he saw. Within a short time, following discussions with the Ipswich Museum, the British Museum, the Science Museum, and Office of Works, Phillips had taken over responsibility for the excavation of the burial chamber. Initially, Phillips and the British Museum instructed Brown to cease excavating until they could get their team assembled, but he continued working, something which may have saved the site from being looted by treasure hunters.[126] Phillips' team included W.F. Grimes and O.G.S. Crawford of the Ordnance Survey, Peggy and Stuart Piggott, and other friends and colleagues.[127] The need for secrecy and various vested interests led to confrontation between Phillips and the Ipswich Museum. In 1935–6 Phillips and his friend Grahame Clark had taken control of the society. The curator, Mr Maynard then turned his attention to developing Brown's work for the museum. Phillips, who was hostile towards the museum's honorary president, Reid Moir, F.R.S., had now reappeared, and he deliberately excluded Moir and Maynard from the new discovery at Sutton Hoo.[128] After Ipswich Museum prematurely announced the discovery, reporters attempted to access the site, so Mrs Pretty paid for two policemen to guard the site 24 hours a day.[129] The finds, having been packed and removed to London, were brought back for a treasure trove inquest held that autumn at Sutton village hall, where it was decided that since the treasure was buried without the intention to recover it, it was the property of Mrs Pretty as landowner.[130] Pretty decided to bequeath the treasure as a gift to the nation, so that the meaning and excitement of her discovery could be shared by everyone.[131] When war broke out in September 1939, the grave-goods were put in storage. Sutton Hoo was used as a training ground for military vehicles.[132] Phillips and colleagues produced important publications in 1940.[133] Rupert Bruce-Mitford: 1965-1971 Following Britain's victory in 1945, the Sutton Hoo artefacts were removed from storage. A team, led by Rupert Bruce-Mitford, from the British Museum's Department of British and Medieval Antiquities, determined their nature and helped to reconstruct and replicate the sceptre and helmet.[134] They also oversaw the conservation of the artefacts, to protect them and enable them to be viewed by the public.[135] From analysing the data collected in 1938-39, Bruce-Milford concluded that there were still unanswered questions. As a result of his interest in excavating previously unexplored areas of the Sutton Hoo site, a second archaeological investigation was organised and in 1965, a British Museum team, later described by Carver as being on a "truly impressive scale", began work, continuing until 1971. The ship-burial site, overseen by Bruce-Mitford, had not been backfilled in the 1930s,[136] so that a plaster cast could be taken from the re-exposed ship impression and a fiberglass shape produced. The mound was later restored to its pre-1939 appearance. The team also determined the limits of Mound 5 and investigated evidence of prehistoric activity on the original land-surface.[137] They scientifically analysed and reconstructed some of the finds. The three volumes of Bruce-Mitford's definitive text, The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, were published in 1975, 1978 and 1983.[138] Martin Carver: 1983-1992 Recent excavations revealed a figure that had been rolled into a shallow grave In 1978 a committee was formed in order to mount a third, and even larger excavation at Sutton Hoo. Backed by the Society of Antiquaries of London, the committee proposed an investigation to be led by Philip Rahtz from the University of York and Rupert Bruce-Mitford,[139] but the British Museum's reservations led to the committee deciding to collaborate with the Ashmolean Museum. The committee recognised that much had changed in archaeology since the early 1970s. The Conservatives' privatisation policies signalled a decrease in state support for such projects, whilst the emergence of post-processualism in archaeological theory moved many archaeologists towards focussing on concepts such as social change. The Ashmolean's involvement convinced the British Museum and the Society of Antiquaries to help fund the project. In 1982, Martin Carver from the University of York was appointed to run the excavation, with a research design aimed at exploring "the politics, social organisation and ideology" of Sutton Hoo.[140] Despite opposition by those who considered that funds available could be better used for rescue archaeology, in 1983 the project went ahead. Carver believed in restoring the overgrown site, much of which was riddled with rabbit warrens.[141] After the site was surveyed using new techniques, the topsoil was stripped across an area that included Mounds 2, 5, 6, 7, 17 and 18 and a new map of soil patterns and intrusions was produced that showed that the mounds had been sited in relation to prehistoric and Roman enclosure patterns. Anglo-Saxon graves of execution victims were found which were determined to be younger than the primary mounds. Mound 2 was re-explored and afterwards rebuilt. Mound 17, a previously undisturbed burial, was found to contain a young man, his weapons and goods and a separate grave for a horse. A substantial part of the gravefield was left unexcavated for the benefit of future investigators and as yet unknown scientific methods.[142] Sutton Hoo Exhibition Hall The recreated burial-ship at Sutton Hoo Exhibition The ship-burial treasure was presented to the nation by the owner, Mrs Pretty, and was at the time the largest gift made to the British Museum by a living donor.[143] The principal items are now permanently on display at the British Museum. A display of the original finds excavated in 1938 from Mounds 2, 3 and 4, and replicas of the most important items from Mound 1, can be seen at the Ipswich Museum. In the 1990s, the Sutton Hoo site, including Sutton Hoo House, was given to the National Trust by the Trustees of the Annie Tranmer Trust. At Sutton Hoo's visitor centre and Exhibition Hall, the newly found hanging bowl and the Bromeswell Bucket, finds from the equestrian grave and a recreation of the burial chamber and its contents can be seen. The 2001 Visitor Centre was designed by van Heyningen and Haward Architects for the National Trust and involved the overall planning of the estate, the design of an exhibition hall and visitor facilities, car parking and the restoration of a fine Edwardian house to provide additional facilities.[144]