Final Paper

Hosch

1

Julia Hosch

Professor Poudrier

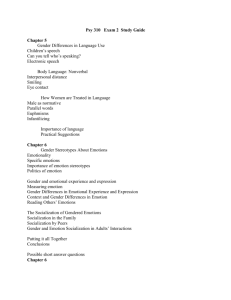

Cognition of Musical Rhythm

11 December 2013

The Power of Music in Decision-Making Situations

1. Introduction

In the field of music cognition research, there exists an expansive literature about how music impacts emotion . A wide variety of perspectives that could possibly affect a listener’s emotions such as rhythm, tempo, tone quality, and genre have already been explored (Schellenberg, Krysciak, & Campbell, 2000; Webster & Weir, 2005).

Even intuitively, it seems more than reasonable that hearing music can impact how we feel and express ourselves. Through these lenses of research, it has become apparent that the study of the effects of music on emotion has earned a place in the field of human psychology.

By the same token, gone are the days that we might consider emotion to be an invalid component of decision-making that should be quashed and left at the door in reasonable debate. Rather, our emotions are our instinctual bias of telling us what is

“right” or “wrong,” and are indicators of our automatic judgments that me make, often before we are conscious that we’ve made them (Libet, Gleason, Wright, & Pearl, 1983).

Emotions play a greater role in our decision-making than we often realize. The point, then, of research in emotion and decision-making is not to prove that emotion impacts judgment, but to inform the general public on how to make better choices. “Informed” in this case would not necessarily mean informed of product choices or pros and cons of a

Hosch

2 situation, but instead informed about the trends and instincts of one’s own mind in given situations with given influences, both internal and environmental.

Imagine a Venn diagram with three major cirlces of emotion, music, and decision-making fields. From three fields, cross-sections of interdisciplinary research emerge. Emotion and music overlap to form music perception and cognition, and emotion and decisionmaking form the field of behavioral neuroscience, commonly called behavioral economics. Decision-making and music intersect in music and marketing studies.

(Although it is certainly plausible that the emotion of customers is definitely a part of this research, I am excluding it from the intersection with emotion because in the realm of advertising, emotion is not the main research focus, only the financial implications of decisions made after priming by music.

In this study, I hope to explore music’s power to induce emotion and how music-induced emotion impacted by music can, in turn, impact economic decisions.

Hosch

3

Figure 1: Venn diagram of the intersections of emotion, decision-making, and music cognition research.

The major fields of emotion, music, and decision-making are the outer and most prominent circles, while the interdisciplinary fields of perception and cognition of rhythm; behavioral economics; and music and marketing research are intersections of these fields. Music and marketing research is probably the closest to the intersection point of all three fields, but because the focus of this research is the direct impact on consumer sales rather than development of psychology, I am excluding it from the emotional circle. This study focuses on the intersection of all three fields, integrating emotion studies into both decision-making and music.

2. Previous research in Music and Emotion

2.1 Music and Emotion: Felt Emotion versus Perceived Emotion

The main questions asked in the field of music psychology center around the debate on whether a listener perceives emotion in music through a process of decoding the emotions expressed by a particular combination of musical features, or whether listening to a musical work causes the listener to experience a particular emotion. The first, the cognitivist position, states that listeners can perceive emotions expressed in the

Hosch

4 music without necessarily feeling those emotions (Hodges, 2011). Arguments for this theory include the widespread ability, regardless of technical talent or even neurotypical development, to discern certain basic emotional traits of music. In one example, Peretz and Gagnon (1999) describe a woman with right and left temporal lobe lesions unable to recognize familiar melodies, but able to discriminate music on the basis of the emotion conveyed. This “affective blindness” demonstrates that even though the woman was unable to actually feel the emotion of the music, she could discern it well enough to use it as her primary mode of definition between pieces. Finally, one of the strongest arguments for this theory is recent research suggesting that music induces emotions in only 55-65 percent of recent listening experiences (Juslin, Liljestrom, Vastfjall, & Lundqvist, 2010).

Because it is unlikely that close to 35-45% of all musical experiences are entirely devoid of all emotion whatsoever, it seems plausible that there must be some attention necessary to create an induced emotion.

The emotivist position argues that listeners actually do feel real emotions that are induced by music, and that perceived emotions and felt emotions can be exactly the same.

Goldstein (1980) conducted a survey of intense emotional experiences, and observed that shudders, tingling sensations, chills, and other physical responses to emotion are also found in response to music. Sloboda (1991) also developed a list of physical reactions that an emotional experience might induce, such as shivers, laughter, tears, racing heart, and sweating. When he asked participants to rank the frequency of these reactions in their experiences listening to music, he found that almost all participants reported feeling these reactions, especially shivers down the spine. Both studies show significant support for the

Hosch

5 emotivist theory because of the high correlation and similarity between physical reactions to music and physical reactions widely seen in emotional situations.

More recently, a third argument has arisen due to the fact that it is possible to have both a perception of an emotion and the feeling of the actual emotion in the same listener, even at different times in the same piece. This theory, suggested by Konecni

(2005), is called the Aesthetic Trinity Theory, or ATT, and states that profound responses to music involve 1) awe, 2) being moved, and 3) thrills. Another study on this idea of the importance of “chills” in music as a physical response was designed by Jaak Panksepp, who hypothesized that because “feelings of sadness typically arise from the severance of established social bonds, there may exist basic neurochemical similarities between the chilling emotions evoked by music and those engendered by social loss.” Research on this response was intended to clarify how music interacts with a specific emotional process of the normal human brain (Panksepp, 1995). Not a great deal of research has been devoted to this theory besides this previous work on chills. However, the theory does suggest that the cognitivist and emotivist positions alone might not explain all of the methods necessary to demonstrate differences between or existence of felt and perceived emotion in music; there may be differences that arise from very specific emotions and very specific physical responses, such as sadness and chills or goosebumps.

3. Previous Research in the fields of Emotion and Economics

3.1. Immediate/Integral Emotions and Expected Emotions

The consequentialist theory of economics is a prominent economic theory that

“assumes that decision makers choose between alternative courses of action by assessing

Hosch

6 the desirability and likelihood of their consequences and integrating this information through some type of expectation-based calculus” (Rick & Lowenstein, 2008). In short, emotions are considered a quantity that could be factored into this ‘calculus’ and determined to be a helpful or hurtful factor.

The problem with this theory is that “emotion” is far too broad concept to be mathematically calculated in its entirety. To help split up the idea of all human emotional capacity, Lowenstein created two types of emotions: expected and integral/immediate

(Lowenstein et al. 2001; Lowenstein & Lerner 2003). Expected emotions are those that one predicts that he or she will feel after an emotional event, either negative or positive.

Often, these predictions of future emotional states are wildly overestimated; people predict that they will be joyful or hurt far longer and far more than they actually feel after the predicted event actually arrives. In one particularly illustrative study, lottery winners were asked to track their daily “happiness levels” and guess their happiness levels after a year based on their windfalls. A year later, those lottery winners reported a significantly lower happiness level as the year before, even though they had anticipated feeling overjoyed and living in luxury for years. (Brickman, Coates, & Janoff-Bulman, 1978).

Through studies like these, psychology has taught us that we are not accurate predictors of our own minds’ feelings in any moment other than the present, and expected emotions weigh heavily in our decision-making abilities.

Immediate emotions, or integral emotions, are entirely different both in nature and their prevalence in psychology studies. Like expected emotions, they arise from thinking about the future consequences of one’s choice. However, unlike expected emotions, they arise at the moment of choice. Therefore, often they can be influenced by “dispositional

Hosch

7 or situational sources” such as a person’s mood at that particular moment of the decision, the sound of the television playing in the background, or the crying of a baby heard while the decision-maker is on the telephone. These are significantly harder to study because they are difficult to isolate: mood is difficult to control for everyone in walk-in psychology studies, and there are simply two many factors to control in any given environment to know what conditions will be the most influential on a given situation, especially if all the environmental distractions are fairly small (Hodges, 2011).

All that said, there have been some studies based on integral emotion, even with the research constraints. One of the most interesting studies of decision-making involving integral emotion was completed by Hirshliefer and Shumway, who found that during years when it was particularly sunny as opposed to cloudy, people were more willing to take risks with their economic stocks. While citizens thought that this willingness to risk was based on the upward nature of the market, actually, the induced emotion given by the presence of sunshine was a mood inducer that gave citizens confidence to undergo riskier business transactions for greater potential payoff (Hirshliefer and Shumway, 2007).

This study shows that integral emotions do have an effect on decisions, but why?

One theory presented is that integral emotions use somatic “tagging.” Somatic markers are affective ‘tags’ attached to sensory images, ‘marking’ each image with an emotional association These marks reduce the number of options under consideration, making decision-making process more efficient, and decision-making to happen automatically without spending brain energy to make a decision (Thompson, 2009).

In sum, these two types of emotion, expected, and integral, change the way that we perceive our own emotions, while we still often believe that we are being highly

Hosch

8 rational. The crucial difference between the two lies in when they are experienced: the

“key feature of expected emotions is that they are experienced when the outcomes of a decision materialize, but not at the moment of choice; at the moment of choice, they are only cognitions about future emotions” (Rick & Lowenstein, 2008). In this study, I will focus primarily on integral emotions because these immediate responses are generated, or at least perceived by the hearing of music.

3.2. Economic Game Theory

There are two “games” heavily studied in the field of behavioral economics. Both illustrate the moral leanings of participants, and both show how different situational variables can change an outcome drastically. The first game is the “Ultimatum game.” In the basic format of this game, there are two players. One player has a set amount of capital, and can choose to give the other player an arbitrary amount of that capital. If the other player accepts the amount that he or she is given, both players keep their new amounts of capital. If the other player rejects, then both of the players lose their capital.

Although in any scenario, both players logically make money from the experience, the second player often becomes indignant and rejects the sum if it appears to be too small.

Because of this, it would seem evident that participants would learn very quickly that cooperating is the best method. Often this is the case; however, variations on this experiment show that with variables such as an audience present for the experiment; a primed mindset of what has been given or received in previous trials; or a vision of the other player; people have been known to change the value amounts given (Pinker, 1997).

Hosch

9

The other is the Dictator game. In this game, the first player (the “dictator”) has a set amount of capita. He or she can choose whether to give any amount to the other player. The second player has no say in the experiment. Although this task might seem obvious, the results of the game and amounts given by the dictator depend on many factors, just like the Ultimatum game. Some of these variables are the same, such as whether an audience is present or whether the Dictator feels as though he or she is being watched. There are also variables specific to this game, such as whether the recipient has been made known to the giver, and if so, if the giver feels as though the recipient is somehow “morally worthy” of the gift. In all of these occasions, givers have been known to increase or decrease their giving amounts based on these external factors (Pinker,

1997).

Both of these games have shown valuable insights into economic factors dealing with emotion, both social and antisocial.

IV. Music and Marketing Research

The field of music and marketing research predominantly focuses on how to best predict the actions of a consumer with priming by the advertiser. Music has become integral to successful advertising, both in direct and indirect ways.

An example of a direct music to consumer advertisement might be the radio jingle concept. The impact of this type of advertising often is not immediate; people do not necessarily immediately act on the commercials that they see on television and run to the store to purchase the item. Therefore, the key niche of effective advertising is to develop a tag or “hook” that will draw in the customer when he or she next has the opportunity to

Hosch

10 act on the suggestion of the advertisement. Radio jingles work like this: although listening to the radio in the car might not put a person in the position to buy a certain brand of milk, when the listener is next in the grocery store and sees the brand, the jingle may come to mind.

The indirect method of music and advertising has no delay between the advertisement and the opportunity of purchase. One highly studied aspect of music’s impact on marketing is the effect of volume on a customer’s actions. Smith and Curnow found that louder and faster music overall sells more of products, but that slower, more soothing music tends to allow customers to make decisions more slowly so that they are happier about their purchases. Customers happy with their purchases are more likely to come back, and the stores make more revenue over longer periods of time. In another example of the impact of music on direct purchasing power in a store, a study on French and German music played on alternating days in a wine section of a grocery store found that people overwhelmingly tended to purchase the type of wine that matched the nationality of the music, whether they recognized that the music was impacting their purchasing decisions or not (Heargraves & North, 1999).

These examples are only two of an entirely full literature of music and marketing research focusing on product placement and musical factors that change customer decisions (such as tempo, key, and even nationality of origin.) Until this point, however, researchers have focused primarily on how these studies can best move capital towards the purchasing of products, and not on furthering the studies on how exactly music impacts the emotions during the decisions made. I hope to look at the next study through this interdisciplinary angle.

Hosch

11

5. Case Study

5.1 Background

Professor Dan Ariely at the Duke Fuqua School of Business and Professor

Eduardo Andrade from University of California wrote a research paper discussing how people’s “fleeting incidental emotions” can become a basis for future decisions. If a decision is made by an individual in a certain emotional state, he or she will tend to repeat the same decisions made in the same contexts even if they no longer feel the emotion that they did in the previous decision. In summary, “given that people often do not realize they are being influenced by the incidental emotional state, decisions based on a fleeting incidental emotion can become the basis for future decisions and hence outlive the original cause of the behavior (i.e., the emotion itself)” (Andrade & Ariely, 2009).

This theory hinges on a few assumptions from previous research. All make logical sense, but it is matter of putting all of the pieces into the puzzle. First, people do not fully realize that immediate emotions might be influencing their decisions. If they do, they tend to correct for the misattribution (Schwartz & Clore, 1983). Once a choice is made, people tend to stay consistent to that choice, if they believe it to be rational. Secondly, when asked to guess the monetary value of products, people tend to be incorrect, sometimes overshooting or undershooting prices by over 300%. However, when asked to measure the price differences between two products, people are significantly closer to accurate—“individuals do not know with high accuracy how much they value different products, but that once they make a decision, they use that initial decision as an anchor for basing later decisions” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Combining these ideas, it

Hosch

12 seems that if people can be kept in ignorance of the fact that their emotions are being affected in an immediate way, the decisions that they make while under that state will last past what the participants themselves would estimate if asked.

From these theories, Andrade and Ariely built an experiment to test their hypotheses.

5.2 Research Methods

In this section, I will briefly summarize the most important points each part

(which Ariely refers to as ‘studies’) for the purpose of contrast when describing my own research based on this experiment.

Study 1. Incidental emotion manipulation

110 students participated in the experiment in a computer-based environment. To begin, all of the participants watched a 5-minute clip of a movie and were asked to then write a personal experience relating to the movie. However, the video clip was different depending on a randomly assigned group affiliation for each participant. Targeted participants, those who would play the receivers in the second part of the study, were assigned to either the angry or a happy condition. In the angry condition, the participants watched an angry movie, watching the actor behave violently, such as breaking furniture.

The happy condition group watched a clip of a comedic television show. The last group, who played the proposers in study two, watched a non-emotional nature documentary.

Study 2. First ultimatum game

Hosch

13

In the second part of the study, targeted participants were told the conditions of the ultimatum game (as described earlier). Specifically, they were instructed that the other player had been given $10 and would choose to share any amount. (In actuality, proposers were only given options of giving $7.5 and keeping $2.5, or keeping $7.5 and giving $2.5 for the purpose of easier post-experiment analysis.)

Study 3. Emotion mitigation

The third part of the study was a filler task so that all participants could neutralize their previous positive or negative emotions from the video stimuli. All pictures shown were neutral in content, and the display lasted about 20 minutes.

Study 4. Second ultimatum game

The fourth part of the study returned to the Ultimatum game. In this study, participants played the reverse role that they played in the second study. In other words, those who had watched the angry or sad movies became the proposers, and those who had watched the nature documentary became the receivers. All other conditions were identical.

Study 5. Dictator Game

In the last study, the proposers from study 4 remained proposers, but played the

Dictator game rather than the Ultimatum game. This “allowed the researchers to investigate the extent to which behavioral consistency and/or false consensus were the

Hosch

14 driving mechanisms.” In other words, the Dictator game allowed for control in case the other results in the forced-choice scenarios gave varying results.

5.3 Results

In the second study (the first Ultimatum game), 93% of the proposers chose to keep the larger amount of money and give the smaller amount, which is logical. Also expected were the results of the rejections by the participants in the receiver groups—the participants primed to be angry were significantly more likely to reject the low amount offered than the group primed with the happy video.

However, these logical results led to more impressive, less intuitive results in

Study 4, even after emotional mitigation. Those primed with the angry videos actually kept less of the money for themselves, giving more to the party that was only primed with a nature video than did the group primed with the happy video. The same result was shown in the Dictator game; the group primed with the angry condition was more likely to keep less money and make a fairer offer than those primed with the happy condition.

In summary, the rationale behind the fairer offers from angry participants was that consistency with past behavior—which was unconsciously impacted by the incidental emotion—had a strong influence on future action, even once the emotion had technically been erased. The point of the study was not to demonstrate that the angry condition made people more willing to share, or even to discuss the implications of the anger condition.

The main premise of the research was to show that emotions from earlier in the study lingered long enough to influence the next decision that the participant made, even though the person thought that he or she was making a logical, rational decision.

Hosch

15

6. Proposal for Research

6.1 Purpose and Hypothesis

For my proposed extension on Ariely’s research, I intend to recreate his study, but change the initial happy or angry movie stimuli conditions to musical stimuli. Ariely states that the video was intended to induce an “integral” emotion, just like the integral emotions heard and felt in music. Because it is significantly harder to study integral versus expected or perceived emotions in music, this could be a key moment to explore questions about the emotivist emotional theory of emotion and music. The point of this research would not be limited to simply looking at the emotivist versus cognitivist emotion theories, however. Since it has already been shown in background literature

(discussed at the beginning of this proposal) that music has an impact on decision-making and market studies, this research might also help to illuminate questions about where emotion might enter this equation. As previously mentioned, most market research has focused on the specifics of gaining as much capital for corporations as possible rather than the implications of study involving emotion. However, this experiment might be able to combine music’s correlation with advertising techniques by introducing emotional study.

There are two possible hypotheses for this experiment:

H1: Listening to music has been shown to have an impact on decision-making in a great many marketing studies. The reason that this is the case may be that the effect that music has on temporary mood can also affect judgment.

Hosch

16

To prove this hypothesis true, it would be necessary to find the same results as in the Ariely study. This would show that induced, integral emotions have the power to stretch into further decisions past the immediate decisions at hand, and that music would be a powerful enough stimulus to induce those emotions.

H2: Listening to music has been shown to have an impact on decision-making in a great many marketing studies. However, this is due to other factors other than emotional manipulation due to music.

If the results of the experiment do not match Ariely’s results, this would show that one of several pitfalls. There are two main reasons that can be discussed this far in advance of the experiment: first, that music might not induce the same valence of emotions as a video; and second, even if the emotion was perceived, it might not be entirely induced in such a short length of time in a laboratory scenario. (Music might take longer than a video to induce the same emotion.) As the experiment unfolds and data is collected, the factors leaning toward one conclusion or another will become clear.

6.2 Participants

In this study, I hope to have at least 50 college undergraduate participants. I hope to test a wide range of participants within these 50, specifically in such variables as musical training and academic area of study. (If too many economics and psychology majors participate in this experiment, it is highly possible that they will have already had

Hosch

17 a large amount of experience with these economics games and they will give biased results based on academic study rather than by musical influence.) I will also consider musical preferences and age.

6.3 Variations on Ariely’s Method

Study 1. Incidental emotion manipulation

To create the groupings of participants in Ariely’s study, I will use musical clips as stimuli for the happy or angry conditions. These stimuli will be chosen based on a

French 2010 study in which 27 selections of classical, non-vocal music were chosen and participants ranked them on different emotions felt during each. This study showed that a) people are able to generally tell the emotions of different musical selections generally come to the same conclusions about thrm; and b) these conclusions are made regardless of the length of the clip of music or the musical experience of the participant (Bigand,

Vieillard, Madurell, Marozeau, & Dacquet, 2010).

Here are selected titles from their study that were shown to clearly demonstrate either “happy” emotions (high valence and or “angry” emotions, as determined participants in the study. The descriptions following each title are copied directly from the experiment.

Happy

10. J. Brahms. Trio, piano, violin and horn, mvt 2. A strident major chord, with the arrangement of the parts and the timbre of the French horn confering a very full sonority.

11. F. Liszt. Poeme symphonique. Powerful orchestral tutti on a major chord, with a triumphant character marked by the strong trumpet presence, and an amplitude envelope which grows drama- tically.

Hosch

18

22. W.-F. Bach. Duetto for two flutes in G, Allegro. Five arpeggiated flute notes from a perfect major chord with a soft timbre and a swift, regular metre.

Angry

12. S. Prokovief. Sonata for piano, no. 3, op. 28. Complex melodic line of nine notes in contrary motion at a lively tempo, marked by aggressive attacks and many dissonances.

17. F. Liszt. Tasso Lamento & Triomfo. Biting explosion of an orchestral tutti on a dissonant chord, strengthened by the percussion in a clearly romantic style of orchestration.

26. D. Shostakovitch. Trio 2 for violin, cello, and piano, moderato. Three snatched intervals in the strings, containing many high and very dissonant harmonics, separating themselves from a low piano note with a rapid tempo.

27. F. Liszt. Totentanz. Aggressive march played in the low register of the piano, in a minor harmony, with a mechanical character indicating a very stable, rapid tempo.

This study neatly fits the criteria for this current experiment for several reasons.

Although it cannot be certain that every participant “felt” the emotion of the music, the instructions given to the participants stated that they should focus on induced emotions rather than what they necessarily perceived from the music that they heard. This means that they were asked to focus on integral, immediate emotions, just like one would feel while watching a video clip. Secondly, these clips have already been tested in a laboratory setting to evoke fairly specific emotions from participants, so I can use the results at face value in my experiment to determine whether they will be “happy” or

“angry” stimuli. The pieces will each be played for five minutes, just as in the Ariely study, and the participants will give attention to them because they will be asked to integrate the clips into their personal lives in writing.

The only foreseeable problem with using this study as reference stimuli is that all stimuli are classical music. It could be that some people have such a strong dislike of

Hosch

19 classical music that they will never experience induced emotions. It also could be that a participant is such an experienced musician that all of the excerpts will be met with an induced reaction based on individual memories of performing or practicing the piece. I hope to have enough participants for data that I will be able to “weed out” these participants as outliers.

Just as in Ariely’s study, my participants will be divided into groups. The first group (the receivers of the Ultimatum game in Study 2) will listen to either happy stimuli or angry stimuli. Upon hearing one of these two stimuli, all members of the first group will be asked to write for 5 minutes about an experience that the music calls to mind, just as Ariely’s study asked participants to do while watching the video clips.

I will also split the emotionally neutral group. (This is a change from the Ariely study, where the neutral group all listened to the nature video.) One half will listen to tracks of nature sounds (just as Ariely’s neutral group heard in the nature documentary) and one group will hear no stimulus at all. The group listening to the neutral stimuli will write about the same prompt as the first group, while the second will write about a neutral experience, such as the last meal that they ate.

Studies 2, 3, 4, and 5

All of the following studies after emotional induction will match (as closely as possible) the procedures outlined in the Ariely study.

Conclusion of the Experiment

Hosch

20

At the conclusion of my experiment, I will ask participants to fill out a questionnaire with biographical information including age, first language, musical experience, personal preference in musical genres, number of psychology or economics classes taken at Yale, and current emotional state. (For the current emotional state, I will ask the participant to rank their emotion on a numbered scale, and I will provide descriptions at each number.) These factors will demonstrate outliers that I should look for when analyzing data as well as potential confounds.

6.4 Data Analysis

Data analysis will match that outlined in Ariely’s study. ANOVA scales will be used to determine statistical relevance of one group’s “generosity” to the other group in the economic games.

6.5 Expected Results

I anticipate that I will see a replicated version of Ariely’s results. Because these musical stimuli have already been tested to induce integral emotiosn, like the integral emotions induced by video clips, it follows that the results will be similar. Perhaps the same trends of generosity from the agitated listeners will be seen as was demonstrated in the agitated group in the video condition. I also anticipate that the decisions made in each emotional state will be statistically different, and that even once the induced states fade, the decisions made will carry over through the rest of the economic games. This would show that music induces emotion, which in turn induces change in decision-making (even after the initial emotion fades!) If this is the case, then this would show that there may be

Hosch

21 a great deal more to learn about induced emotions and the effect of induced emotions and music psychology. .

7. Conclusion

After this study is complete, I hope to look at future research implications for my hypothesis about music’s connection with emotion and decision-making research. The fairly obvious application for this type of study is in marketing and business, but I hope also to extend this research for use in general public knowledge in daily situations of decision-making.

One of the simplest ways to transfer these results to daily life might be to reconsider methods of practicing for stressful events. For example, if my hypothesis is true, people might consider listening to calm music while practicing to give public speeches, or while preparing for stressful interviews. By practicing making decisions in an emotional state partially controlled by environmental factors of your choosing (such as calm music), perhaps those situations could be made easier in real-world settings. In the same vein, perhaps people needing to give inspirational messages, actors and actresses, or even teachers could practice giving lessons while listening to music with an upbeat, bright tempo so that the energy imparted by the music could be transferred again while giving the speech.

As data comes to fruition, I hope to extend this study further and edit this proposal to make it more complete. Some additions I will make to this proposal before actually completing the research will be:

Hosch

22

1. Adding more stimuli in other genres to accommodate for the problem of preference previously mentioned.

2. Continuing research on other theories besides cognitivist and emotivist theories that might further my opinion on how best to impart musical stimuli.

3. Researching further in marketing literature in case there are other applications to this sort of study that I might change the type of game that I ask participants to play, or that I ask them to answer at the end of the survey.

In conclusion, while this proposal is not fully complete, it provides a basic outline for the project that I hope to complete this spring analyzing a theory of music, emotion, and decision-making. The results can and should be repeatable for further study, and already show promise for furthering the field of music cognition research.

Hosch

23

Bibliography

Andrade, Eduardo B., & Ariely, Dan. (2009). The enduring impact of transient emotions on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,

109 (1), 1-8.

Bigand, E., Vieillard, S., Madurell, F., Marozeau, J., & Dacquet, A. (2005).

Multidimensional scaling of emotional responses to music: The effect of musical expertise and of the duration of the excerpts. Cognition & Emotion,

19 (8), 1113-1139.

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 36 (8), 917-927.

Custers, R., & Aarts, H.. (2010). The Unconscious Will: How the Pursuit of Goals

Operates Outside of Conscious Awareness. Science, 329 (5987), 47-50.

Goldstein, A. (1980). Thrills in response to music and other stimuli. Physiological

Psychology, 8(1), 126-129.

Hul, M.K., Dube, L., & Chebat, J.. (1997). The impact of music on consumers' reactions to waiting for services. Journal of Retailing, 73 (1), 87

104.

Juslin, P. N., Harmat, L., & Eerola, T. (2013). What makes music

Hosch

24 emotionally significant? Exploring the underlying mechanisms. Psychology of

Music .

Konechi, V. J. (2005). The aesthetic trinity: Awe, being moved, thrills. Bulletin of

Psychology and the Arts, 5(2), 27-44.

Libet, B., Gleason, C.A., Wright, E.W., & Pearl, D.K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain, 106(3), 623-642.

Liljeström, Simon, Juslin, Patrik N., & Västfjäll, Daniel. (2012). Experimental evidence of the roles of music choice, social context, and listener personality in emotional reactions to music. Psychology of Music . doi: 10.1177/0305735612440615

Milliman, R. E. (1982). Using background music to affect the behavior of supermarket shoppers. Journal of Marketing , 46 , 86-91.

North, A. C.; Heargraves, D.J. (1999). The influence of in-store wine selections. Journal of Applied Psychology , 84 , 271-276.

Panksepp, Jaak. (1995). The Emotional Sources of "Chills" Induced by Music. Music

Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13 (2), 171-207. doi: 10.2307/40285693

Peretz, I.,Gagnon, L., and Bouchard, B. (1998). Msuic and emotion: Perceptual determinants, immediacy, and isolation after brain damage. Cognition, 68, 111,

14.

Rick,S., Loewenstein, G. (2008). Handbook of Emotion, Third Edition: The Role of

Emotion in Economic Behavior.

Guilford Press.

Schellenberg, E.G., Krysciak, A. M., & Campbell, R.J. (2000). Perceiving

Hosch

25

Emotion in Melody: Interactive Effects of Pitch and Rhythm. Music Perception:

An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18 (2), 155-171. doi: 10.2307/40285907

Scherer, K. R. (2004). Which Emotions Can be Induced by Music? What Are the

Underlying Mechanisms? And How Can We Measure Them? Journal of New

Music Research, 33 (3), 239-251. doi: 10.1080/0929821042000317822

Sloboda, J. (1991). Musical structure and emotional response: Some empirical findings.

Psychology of Music, 19, 110-120.

Webster, GregoryD, & Weir, CatherineG. (2005). Emotional Responses to Music:

Interactive Effects of Mode, Texture, and Tempo. Motivation and Emotion, 29 (1),

19-39. doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-4414-0