When humans attackNewSci

advertisement

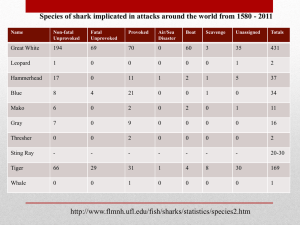

When humans attack: The fallout of the shark slaughter 01 May 2012 by Henry Nicholls Magazine issue 2862. New Scientist We are killing so many of these predators that their numbers are plummeting. New Scientist looks at the consequences of taking out the ocean's top predators ON 15 August last year, Gemma Redmond was sitting on a beach in the Seychelles while her husband, Ian, snorkelled offshore. They were on their honeymoon. Suddenly she heard Ian call for help. Then there was a "most awful scream". A shark had bitten off his arm and taken a huge chunk out of one leg. A boat brought him back to shore but he died of blood loss shortly afterwards. It was a horrific event but an extremely rare one: Ian was one of just 12 people killed by sharks last year. Even that figure is unusually high - on average, fewer than five people are killed each year in unprovoked attacks. By contrast, people kill around 40 million sharks annually. As a result of this slaughter, the number of sharks is plummeting. Instead of fearing sharks, we should fear for them. But does it matter if we kill these killers, or will there be big knock-on effects throughout the ocean? Sharks used to be regarded as a nuisance by most of the fishing industry. Many were caught, though seldom deliberately. During longline fishing for species like tuna, for instance, sharks were a common by-catch. Until 1999, no global records were even kept of how many sharks were caught. In recent decades, though, sharks have become valuable, largely because of the growing hunger for shark fin soup. Once regarded as the food of emperors because of the cost and elaborate preparation required, this Chinese dish is growing more popular as the country becomes wealthier. See gallery: "Shark on the menu: Species hunted for their fins" So what's been the impact of this growing demand? The abundance of fish is usually calculated from catch data, but official records only go back a decade. What's more, they are far from accurate, says Daniel Pauly of the Fisheries Centre at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. "We are not just talking piddling, precision-type errors," he says. "The underestimation can be 30 to 50 per cent in developed countries, and 100 to 400 per cent in developing countries." So there are only a few regions where researchers have been able to work out how shark catches have changed over time. By combing through the logbooks of the US longline fishing fleet, for example, Julia Baum of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, and colleagues found that in 14 years - from 1986 to 2000 - shark catches in the north-west Atlantic Ocean declined by more than half. They concluded that populations of scalloped hammerhead, white and thresher sharks had each declined by more than 75 per cent (Science, vol 299, p 389). Precipitous decline In a follow-up study based on a similar analysis of historical catch data, the same team estimated that in the Gulf of Mexico, the abundance of the oceanic whitetip shark declined by more than 99 per cent and the silky shark by more than 90 per cent. It is likely that similar precipitous declines are occurring in most oceans. Part of the reason is that sharks are slow breeders. They can take years to reach sexual maturity and produce only a few eggs or a handful of pups at a time. A few live-bearing species, such as the basking shark, are thought to have gestation periods as long as three years - longer than an elephant. This makes them much more vulnerable to exploitation than many other fish species. Some species could be lost altogether. The metre-long Pondicherry shark of south Asia has not been seen since 1979. Several species of bottom-dwelling angel sharks are now regarded as critically endangered. Should we care if shark numbers are plummeting? It is clear from studies of other ecosystems that the effects of removing top predators can cascade down the food chain, altering the entire ecosystem. However, it is extremely difficult to study the effects of removing sharks, not least because there are hundreds of different species, some operating at great depths, others sticking closely to coral reefs, others to continental shelves and yet others covering thousands of kilometres in the open ocean. What's more, new species are still being discovered. "We're just guessing at the moment," says Callum Roberts at the University of York in the UK, who studies our impact on the oceans. "It's a bit like trying to reassemble a very complicated mechanism from its parts without having a good blueprint of what the mechanism once looked like." Until a decade ago, the only evidence of the effects of killing sharks was largely anecdotal. In South Africa, for instance, the erection of large-meshed nets off swimming beaches to catch big sharks led to an explosion in the abundance of smaller shark species near the shore, and a decline in small fish. Similarly, a shark fishery operating off Tasmania was blamed for the collapse of a neighbouring crayfish farm. The removal of sharks is thought to have boosted the numbers of crayfish-chomping octopuses in the coastal waters. Both cases were open to question but appear to be examples of changes to the top of a food chain cascading downwards. The strongest evidence comes from a study of the east coast of North America. Based on a combination of coastal surveys and fishery data, it found that there have been drastic declines in all 11 species of large sharks, with scalloped hammerhead populations crashing by 98 per cent and bull sharks by 99 per cent since the 1970s. At the same time, the populations of rays, skates and smaller sharks have all boomed. This sudden abundance of smaller predators resulted in the collapse of a century-old scallop fishery (Science, vol 315, p 1846). This last link was confirmed by using barriers to keep cownose rays out of some areas; scallops survived only in these areas. Really scared This suggests a textbook ecological pyramid with a few top predators having a big effect on more abundant prey species that feed on even more numerous small fish and invertebrates (see diagram). But the latest findings suggest sharks don't just affect the numbers of their prey - they affect their bodies and behaviour, too. In 2005, marine biologists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, set out to the Line Islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean to compare the marine communities living on different reefs. They found the reef systems least disturbed by people, Kingman and Palmyra, had the healthiest corals and supported the greatest biomass of fish ever recorded on a reef (PLoS One, vol 3, p e1548). What astonished them, though, was the abundance of sharks. The vast majority of the fish biomass consisted of sharks, and the biomass of prey fish was actually lower than that on more disturbed reefs nearby. "This turns the textbook trophic pyramid on its head," says Sheila Walsh, an expedition member now at the Nature Conservancy in Virginia. "It doesn't even seem energetically possible." The only explanation is that small fish are being eaten as fast as they breed, so their biomass at any one time is much lower than that of their longer-lived predators. The fish with lots of predators behaved differently too. "They are just really scared," says Walsh. So scared that she and her fellow divers found it hard to catch fish for further study. "Man, are they good at escaping." When the researchers dissected the prey fish, they found they had slender livers and were storing very little fat (Journal of Fish Biology, vol 80, p 519). By contrast, specimens of the same species from sites with fewer sharks were consistently fatter, Walsh says. "You open them up and their intestines are just lined with fat." Walsh suspects prey fish may grow more slowly when there are fewer sharks, making reefs less productive. "These results are a warning to not take the simple assumption of a basic ecological model that says get rid of predators you'll have more prey," she says. "Maybe, in fact, having sharks around makes for faster, more productive fisheries. A lot of our findings are pointing in that direction." So there is still much we don't understand. The uncertainties tend to be glossed over by those campaigning to save sharks. "Mostly what you find is fairly glib statements that loss of sharks will have profound consequences for the ecosystem," says Roberts. "There are these kind of arm-waving arguments about the importance of top predators." These claims may well be correct, he says, but proving them is another matter. "We've seen these top-down effects in a whole range of smaller-scale experiments using intertidal shore fauna, for example, but it is just much harder to grasp at the large scales and in the non-experimental settings that you have with big populations of sharks." And it may now be too late to ever fully understand our impact. Even if sharks survive and their numbers eventually recover, things may not go back to the way they were. "Often we find that ecosystems have shifted in ways that mean the productivity of old - or the biomass of old - cannot be recreated," says Roberts. "There are various pieces that have been taken out of the food web. Those connections will probably take a very long time to reinstate." The role sharks play in the ecosystem is not the only reason for being concerned about them. For starters, no one is going to make any money from catching sharks if there are none left to catch. In some regions, there are efforts to ensure that shark catches are sustainable. And in many places, sharks may be worth more alive than dead. Diving is one of the fastest growing sectors of the tourism industry, and sharks are a considerable draw. Many divers visit the Galapagos in hope of seeing vast schools of hammerheads and other sharks, for instance. Dive tourism is worth at least $15 million a year to the islands, estimates Alex Hearn, a marine biologist at the University of California, Davis, several times more than is generated by fishing in the protected Galapagos waters. "If well managed, dive tourism can bring income to local communities," Hearn says. "It can also serve as a deterrent, because if there's a bunch of divers, it's unlikely a big industrial longliner is going to come in and pull out all the sharks." Clearly, there is value in sharks other than their fins. But will we recognise them in time? "The losses of megafauna are happening incredibly rapidly while the world sleeps," says Roberts. "I worry that we're going to be too late for many species." Stopping the slaughter The five sharks cruise towards me in the warm, shallow water. One lunges towards the beach, almost stranding itself on the sand. It's not me it's after, but a shimmering shoal of tiny silver fish, which escape the shark's jaws by leaping into the air, making the surface of the water boil. At a metre long, these baby blacktip reef sharks are no threat to people. In fact, they are positively cute. Which is just as well, given that dozens of them are patrolling the lagoon around the tiny resort island of Soneva Fushi in the Maldives. Lagoons normally act as a nursery for juveniles, but for years there were no pups at all in this lagoon. However, since the Maldives banned shark fishing in its waters in 2010, at the urging of its tourist industry, they have reappeared. It is not possible to be sure if the sharks are back because of the ban, says the resort's resident marine biologist Kate Wilson, but it is certainly an encouraging sign. A few other countries, including the Bahamas, have also banned shark fishing, while others have taken measures to outlaw or limit "finning", the practice of cutting sharks' fins off and discarding the body. However, local bans cannot save ocean-going species. What's more, with dried shark fins fetching up to $700 per kilo, enforcing bans will not be easy. Ultimately, the only way to protect sharks is to reduce the demand for their fins, says Daniel Pauly of the University of British Columbia. "This product is so outrageous. You have the issue of waste because you use only part of the shark, you have the issue of cruelty because you cut off the fin, you have the issue of snobbery, with people only eating it to impress their neighbours," he says. He thinks getting shark fin soup off the global menu is a battle that can be won. With several hotel chains in China announcing earlier this year that they were taking the dish off the menu, there are reasons for optimism. Michael Le Page, with additional reporting by Henry Nicholls Is it safe to go back into the water? With fewer sharks in the sea, is it at least safer to venture into the waters? Not at first sight. The number of unprovoked shark attacks worldwide has been rising steady, from less than 100 between 1900 and 1910 to over 600 between 2000 and 2010, according to the International Shark Attack File. However, the main reason for this is that there are a lot more people swimming, surfing and diving in the sea, and also better reporting of attacks. The number might be much higher were it not for the decline in shark numbers. But as the number of shark attacks is influenced by everything from the economy and the weather to people learning how to behave around sharks, there is no way to be sure of this.