Phenomenal and Perceptual Concepts

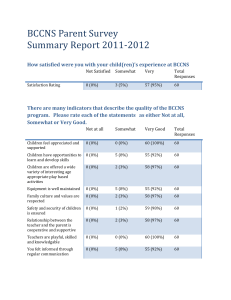

advertisement