Research Paper - Stephanie Newman

advertisement

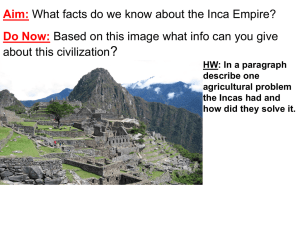

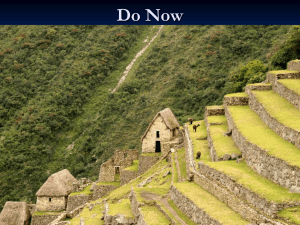

Stephanie Newman November 18, 2010 Societies of the World 40 Research Paper Inca Stonework: A Reflection of the Inca Value System Of all that is awe-inspiring in the Inca Empire, the civilization’s stonework has remained among its most remarkable features. Inca stone structures have long mystified both travelers and researchers. Those who visit sites such as Cuzco, Pisac, Saqsaywaman, and Ollantaytambo are “often astonished at the beauty and ingenuity of Inca stone-working,” and Inca scholars themselves still have some trouble explaining the marvel of Inca stonework (D’Altroy 2002:309). The attributes of Inca stonemasonry that evoke the greatest astonishment are the colossal size of the stones used and the meticulous manner in which they are fitted together—a style “with joints so perfect as not to permit the penetration of a penknife” (Jessup 1934:239). One approach to investigating Inca stonemasonry is to examine its relationship to the prominent values that characterize Inca society. In using this approach, it becomes clear that Inca stonemasonry is a reflection of two such values: 1) Inca organizational efficiency, and 2) Inca relationship to land. This conclusion is further supported in a case study of Ollantaytambo, one of the most outstanding Inca sites of Inca stonemasonry. In looking specifically at Ollantaytambo, both the principles of Inca organizational efficiency and relationship to land prove essential to understanding the site’s construction and layout. 1 In the Inca Empire, organizational efficiency was a principle of extensive pertinence. Administrative order had extreme importance to the Incas, and their most notable strategy for creating and maintaining such order was their decimal system. The Incas used a decimal system of base ten to organize “able-bodied heads of household men into units of 10, 50, 100, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000,” and to “tabulate labor for both civil and military duties, including farming, herding, and artisanry, as well as portage, guard duty, and war service” (D’Altroy 2002:233). Because Inca administration relied heavily on correct census information, the process of census-taking was also scrupulous: “People of each sex were assigned to one of ten categories that corresponded to their life stage or ability to do useful work…the Incas kept separate khipu [knot records] for each province, on which a pendant string recorded the number of people belonging to each category” (D’Altroy 2002:234-235). Beyond the decimal system, the value of organization is also very visible in the Incas’ political hierarchy, which was headed by a ruler known as the “Sapa Inca.” Below this emperor were elite classes of ten royal kin groups called panaqa, ten more noble kin groups, and finally “Incas by Privilege,” who had inhabited Cuzco at the time that the mytho-historic Inca founders arrived (D’Altroy 2002:89-91). Given that organizational efficiency permeated several aspects Inca society, it is only fitting that the Incas carried over this organizational efficiency to the process of stoneworking. In Inca stonemasonry, organizational efficiency first manifests itself in the manner of construction. The steps taken to build stone structures were themselves systematic, consisting first of quarrying, then of cutting and dressing, and last of 2 fitting and laying. In this methodical approach to stonemasonry, the Incas would start by traveling to quarrying sites, where they selected and located the rocks to use. At quarries like Rumiqolqa, which is the site that “supplied much of the andesite used in the construction of Cuzco,” a network of roads and ramps connected separate quarrying areas within the site (Protzen 1985:162-164). Such quarrying areas were differentiated and organized based on rock quality or type; for instance, in Rumiqolqa, a high quarry was the source of andesite that could be extracted in thin slabs, whereas an east quarry provided columnar rock and central quarries provided rock that was boulder-like. After quarrying, the Incas would cut and dress the stones in a similarly methodical and organized fashion. They used river cobbles as hammerstones and differentiated these hammerstones based on size. The largest ones served to cut and break up the quarried blocks, while the medium-sized and small-sized hammerstones were used to dress the stones by respectively cutting the surfaces and finishing the edges (Protzen 1985:164-170). This process was surprisingly efficient; in a hands-on experiment, architect Jean-Pierre Protzen emulated the Inca hammerstone techniques on an andesite block and was able to dress three sides and cut five edges in only ninety minutes (Protzen 1985:174). Accordingly, the process of fitting and laying is also thought to have been systematic: The Incas, when building a wall, typically left the apparent upper faces of already set stones uncut until the next stone was ready for laying. This next stone was first carved on at least two faces, its bedding face and one lateral face. The shapes of these faces were then cut out of the already set stones to receive the new one. Thus, each stone was individually fitted to its immediate neighbors. [Protzen and Nair 1997:158] 3 This strategy for building with stone allowed the Incas to achieve a remarkably tight fit between stones while avoiding a longer than necessary trial-and-error process (D’Altroy 2002:310). This methodical construction mechanism, taken with the orderly arrangement of the quarry sites and the productive nature of the cutting and dressing process, exemplifies the organizational efficiency with which the Incas approached stoneworking. Interestingly, this principle of organization also applies to both the aesthetics and the function of Inca stonework. Stylistically, the level of technique in Inca stonework corresponds to the significance of the building itself. Three levels of stylistic sophistication existed, ranging from most to least refined. Stonework in the first and most advanced style exhibits the most careful fit and appears in important buildings in Cuzco. The stonework in less consequential buildings outside the capital tends to fall into the least advanced style of stonemasonry, with walls created from easy-to-find fieldstone (Niles 1987:277-278). This direct correspondence of stylistic sophistication with the level of the building’s importance reflects both aesthetic and conceptual order in stonemasonry. A more specific example of visual organization can be seen in the incorporation of niches into Inca stonework. Niches were very common in Inca stone buildings, and niche design seems to have followed strict patterns of symmetrical arrangement: “[Niches] are always placed in a symmetrical composition with respect to the doorways, and they are disposed symmetrically on facing short walls…Niche placement is fairly constant in relation to the level of the ground, with standard niches [placed]…about 1.25m above the level of the ground” 4 (Niles 1987:279). The uniformity among niche placement and shape—niches are almost always rectangles or trapezoids—is again indicative of the visual order in Inca stonemasonry. Beyond such visual order, compelling organization again comes through in the functional component of Inca stonework. While sites of stonework displayed aesthetic organization, many of them also served an organizational purpose within the empire. A prime example of this occurs in the Yucay terraces, which were used for agricultural purposes on Inca ruler Huayna Capac’s estate. The large layout of the terraces features perfectly straight north-south double roads and a dual stair system to facilitate easy movement between adjacent terraces. Nonetheless, movement within the site is still limited; it is difficult to access terraces across the road from one another because it is only possible to cross the road by bridge—but this limited access existed for an organizational reason. (Niles 1999:208-220). In explaining the design of these terraces, archaeologist Susan Niles notes, “It is all about control. [The movement of pedestrians and workers] around the system was circumscribed…The historical documents assure us that the workers on the estate represented a number of different ethnic groups, and that each group worked on a different terrace, named for that group” (Niles 1999:228-229). The Incas used the layout of the Yucay terraces to organize laborers within the estate, thereby demonstrating the concept of organizational efficiency through the arrangement of their stone structures. Just as the Incas’ value of organizational efficiency is very visible in their stonework, so their complex relationship to land makes itself equally evident in 5 their stonework. For a long time before the emergence of the Inca Empire, Andean peoples had already developed a relationship to their landscape that was rich in both its practical and spiritual components. On a practical level, the unique climate of the Andes called for significant adaptation on the part of its inhabitants. Because the Andes are so steep, an impressive amount of microclimates form within a given region. As a result, a vertical archipelago settlement structure emerged among its peoples, in which different groups of an ethnicity (namely, kinship groups called ayllus) were “distributed across the landscape” so that its members would have “access to a full complement of production zones…[to] produce the basics of life themselves in concert with their neighbors” (D’Altroy 2002:32-33). On a more spiritual level, Andean mythology incorporated supernatural beliefs about the earth and the sky; earthly elements were given the qualities of deities, as “stones could come alive…or a mountain peak, a rocky outcrop, or a spring could be an ancestor or a guardian spirit” (D’Altroy 2002:142). In the Andean cosmic origin myths, the creator Viracocha grew disappointed in humanity and ended the first age of the world he created by turning his human beings into stone. In Inca state myths, the founder-king Manco Capac originated from a stone cave (Urton 1999: 35-45). The earth—and especially stone—played a profound role in Inca culture. This complex relationship between the Incas and their landscape is wellrepresented in their stonework. Once again, terraces can be used as an example of stonework that embodies both the practical and conceptual aspects of this relationship. On a practical level, Inca terraces “reshaped the land for human needs by providing level spaces for dwellings, ceremonial structures, and agriculture” 6 (Nickel 1982:200). In building terraces, the Incas characteristically imposed order on the landscape itself and created an agricultural strategy for irrigation. Often, the placement and design of terraces were carefully calculated to take advantage of the environment. Terraces at Sima Pukyu, for instance, were strategically placed at a ravine where water from an underground stream seeped through the bottom layer of scree; in this way, the Incas were able to irrigate the tricky stream. Some terraces, like those at Choquebamba, span a vertical distance of 700 meters—a result of the Incas’ attempt to make the most of the varying microclimates at different altitudes (Protzen 1993:32-33). And so, in this sense, terraces illustrate the Incas’ effort not simply to survive in the Andes, but to exert power over their landscape. Nevertheless, as Protzen importantly points out, the Incas’ “power over nature was tempered by the veneration the Incas had for nature” (Protzen 1993:33). While the Incas manipulated their landscape with the terraces they built for practical purposes, they also preserved—even better, enhanced—its natural form: The craft of building terraces became the art of landscaping. The big sweeping arcs of the terraces…bring out the contours of the hillsides and transform the barren screes into gardens…Thus when they built terraces or other structures, the Incas were very careful to harmonize the natural with the man-made. [Protzen 1993:33] For instance, water in the terraces was not merely “controlled” by the Incas for irrigation. Rather, there existed a dualistic harmony between the water and the stone. At the Yucay terraces, water cascaded from one level of terrace to another through vertical grooves in stairway columns. Niles recalls that, as some grooves are entirely exposed and others are partially covered by other stones, “The effect is to have alternating squares of stone and water, which is beautiful when there is a good 7 gush of silver water cascading down the groove” (Niles 1999:219). Another harmonious feature of Inca terracing is the coexistence of the vertical and horizontal lines within the stepped form. Both “verticality” and “horizontality” are concepts that appear in Inca life. “Verticality” is present ecologically with the development of the vertical archipelago system in the Andes, while each microenvironment occurs on its own “horizontal” level within the landscape (Nickel 1982:201-202). Thus, while Incas used stone terracing to exert control over their landscape, they also used terracing to conceptually encompass their idea of the landscape and to express a harmony between man and nature. Of the many outstanding sites of stonemasonry throughout the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo is one of the most renowned. It is situated in the area where the Urubamba and Patakancha rivers converge, in the Urubamba Valley. Pachakuti, the ninth Inca ruler given the most credit for expanding the Empire, turned Ollantaytambo into his own royal estate after defeating its original inhabitants, burning the town, and then initiating its elaborate reconstruction (D’Altroy 2002:65; Protzen 1993:19). Because Ollantaytambo was still in construction during the time of the Spanish conquest, the site provides especially valuable insight into Inca stonework (Gasparini and Margioles 1980:68-72). Both the Inca principle of organizational efficiency and the intricate Inca relationship to land appear to have had significant influence on the construction and design of Ollantaytambo. Organizational efficiency at Ollantaytambo is first evident in the structure of the labor that went into the site’s construction. Lisbet Bengtsson, an archaeologist who conducted specialized field research at Ollantaytambo, hypothesizes that, 8 because the preparation of the building blocks were completed at several construction sites, there must have been a vertical organization of labor. The structure he suggests is as follows: One person—or a pair of leaders, a type of leadership common in the central Andes— might have been in charge of the work in the quarries, another of the transportation, and a third of the construction. These leaders did not co-ordinate the efforts made in the different sectors. Instead, each sought to fulfil any demands made on them from higher levels in society. The leaders at those higher levels to some extent gave instructions at least about the end product wanted. [Bengtsson 1998:128-129] In this structure of labor, both hierarchy and separation of tasks act as the organizing framework. Hierarchically, there are higher-level overseers to direct the laborers in their manual work—work that is separated into tasks of quarrying, transporting, and building. Bengtsson further elaborates on a horizontality of labor that seems to have existed during Ollantaytambo construction. Such horizontality of labor relates to the unfinished blocks left at Ollantaytambo, which have distinct preparation marks on their different sides; one side might contain marks of one shape or size, while the other side of the block might have marks of a different appearance. One explanation for these marks is that two laborers worked on either side of the block at once, implying a horizontal mechanism among those workers within the same labor level. This horizontal structure would have extended to task groups who completed their respective duties on the same site (Bengtsson 1998:129). The division of labor at Ollantaytambo, both vertical and horizontal, recalls the systematic efficiency with which the Incas approached their stonemasonry. 9 The design of Ollantaytambo itself also speaks to such methodical organization. The site was laid out on a grid. Its shape is trapezoidal, but it is rectangular in character, with cross-streets running parallel to each other. The site is divided in two by the Patakancha River, which separates Ollantaytambo into an eastern planned sector and a western ceremonial sector (Gasparini and Margioles 1980:68-72). This regularity of design is most visible in the settlement area of Ollantaytambo. The eastern sector of Qozqo contains “four longitudinal and seven transversal streets”; similarly, the settlement Araqhama “also displays an orderly street pattern” (Protzen 1993:26-27). Another very interesting organizational feature of Ollantaytambo is the kancha, a distinct type of living compound in Ollantaytambo’s settlements. The design of the kancha is based on strict organizational principles, as archaeologist Graziano Gasparini details: Each rectangular block, surrounded on all four sides by narrow streets, contains two completely independent living compounds with a single entrance to each compound opening onto opposite streets. The two units duplicate the same design, comprising four rooms set around a quadrangular courtyard. [Gasparini and Margioles 1980:187] The kancha therefore demonstrate both dualistic and quadripartite order. The careful planning the kancha and the grid of streets at Ollantaytambo is yet another expression of the Incas’ value for organization. At the same time as it displays organization, Ollantaytambo’s design powerfully conveys the Incas’ deep relationship to their land they inhabited. The stone-water duality is very present at Ollantaytambo. Within the settlements, the Incas capitalized on the convenience of the streets’ slope toward the river by building water channels that slanted down along the longitudinal streets. These 10 water channels delivered fresh water to each kancha compound and perhaps carried away waste (Gasparini and Margioles 1980:68-72). The Incas cleverly protected the terraces at Ollantaytambo from harmful winds and kept them a slightly higher than average temperature by situating the terraces down into the outwash fan of the Patakancha River. (Protzen 1993:33). The terracing at the site is also beautiful and elaborate, and according to Protzen, the terraces have “taken on proportions that far exceed those necessary for survival,” becoming “a symbol of man’s power over nature, his abilities to reshape and transform the land” (Protzen 1993:32). Nonetheless, the terraces at Ollantaytambo do not intrude on the natural landscape. As always, the Incas preserved and worked within the land’s natural form, so that the “eleven expansive terraces that face the settlement gracefully blended in with the natural slope of the piedmont” (D’Altroy 2002:137). And so, in the stonework of Ollantaytambo, the Incas use the land to their practical advantage while still upholding their respect for the land’s natural form. A more spiritual layer of the Incas’ relationship to their landscape is represented in the holy shrines of Ollantaytambo. Several shrines are located on the site, the most renowned of which is the main temple. The main temple, also known as the Fortaleza, consists of “six exquisitely worked vertical ashlars of pink rhyolite” (D’Altroy 2002:133). In the area around the Fortaleza are the fountains of the sanctuary Inkawatana and several intricately carved rock faces (Protzen 1993:28). Shrines outside of the main temple include the carved stone of Sirenayoq, which is “flanked by a niched wall and bathed by the waters of the Urubamba” (Protzen 1993:29). In both the fountains of Inkawatana and the water-bathed, niched wall of 11 Sirenayoq, the stone-water duality seen so often in Inca stonework reappears. In contrast to the terraces, though, where stone and water come together for a practical (albeit aesthetic) purpose, the stone-water duality at these shrines assumes spiritual significance. Thus, at Ollantaytambo, the spiritual facet of the Inca relationship to land is captured in addition to the practical component. In moving beyond the specific site of Ollantaytambo to a more comprehensive assessment of Inca stonework, it seems fair to say that Inca stonework integrates key Inca values in a variety of ways. The principle of organizational efficiency appears again and again in Inca stonework—the step-bystep quarrying, dressing, fitting system of stone construction; the vertical and horizontal structure of stoneworking laborers; the symmetry of common niche designs; and the highly planned grid layout of Ollantaytambo are all examples of the organizational efficiency so characteristic to the Inca Empire. The Incas’ multifaceted relationship to land is also a recurrent theme of the Empire that is essentially incorporated into Inca stonework, whether this be through terraces that engineer irrigation maneuvers or through holy stone shrines of Inca worship. Perhaps most meaningfully, the study of Inca stonework attests to the fact that the Inca value system was not an isolated set of conceptual ideals. The investigation of Inca stonework proves that Inca values were assimilated into the daily operations and developments not only of stonemasonry, but of Inca life in general: labor administration, architecture, agriculture, and even spirituality. 12 Bibliography Bauer, Brian S. 2004 Ancient Cuzco : heartland of the Inca. 1st ed. University of Texas Press, Austin. Bengtsson, Lisbet 1998 Prehistoric stonework in the Peruvian Andes : a case study at Ollantaytambo. Vol. 44; no. 10, Göteborg University, Dept. of Archaeology :Etnografiska museet, Göteborg, Sweden. D'Altroy, Terence N. 2002 The Incas. Blackwell Publishers, Malden, MA. Gasparini, Graziano, and Luise Margolies 1980 Inca architecture. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Jessup, Morris K. 1934 Inca Masonry at Cuzco. American Anthropologist 36(2):pp. 239-241. Kendall, Ann 1985 Aspects of Inca architecture : description, function, and chronology. Vol. 242, B.A.R, Oxford, England. Nickel, Cheryl 1982 The Semiotics of Andean Terracing. Art Journal 42(3, Earthworks: Past and Present):pp. 200-203. Niles, Susan A. 1987 Niched Walls in Inca Design. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 46(3):pp. 277-285. Niles, Susan A. 1999 The shape of Inca history : narrative and architecture in an Andean empire. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City. Protzen, Jean-Pierre 1985 Inca Quarrying and Stonecutting. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 44(2):pp. 161-182. Protzen, Jean-Pierre, and Stella Nair 1997 Who Taught the Inca Stonemasons Their Skills? A Comparison of Tiahuanaco and Inca Cut-Stone Masonry. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 56(2):pp. 146-167. 13 Protzen, Jean-Pierre, and Robert Batson 1993 Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. Oxford University Press, New York. Urton, Gary 1981 At the crossroads of the earth and the sky : an Andean cosmology. Vol. no. 55, University of Texas Press, Austin. Urton, Gary 1999 Inca myths. 1st University of Texas Press ed. University of Texas Press, Austin. 14